The Padres took two of three from the Rockies to complete a long road trip with a record of 6-3. That’s a result anyone would have been happy to sign up for before the trip began, but there’s no denying the way it ended left a sour taste. Coors Field is not a normal place to play baseball, and you want to be careful making adjustments based on the outcomes in baseball’s Bermuda Triangle. But the Padres will make one more trip to Coors this season, and there are clearly aspects of playing in that strange gravity that do in fact warrant an adjustment.

Game 1

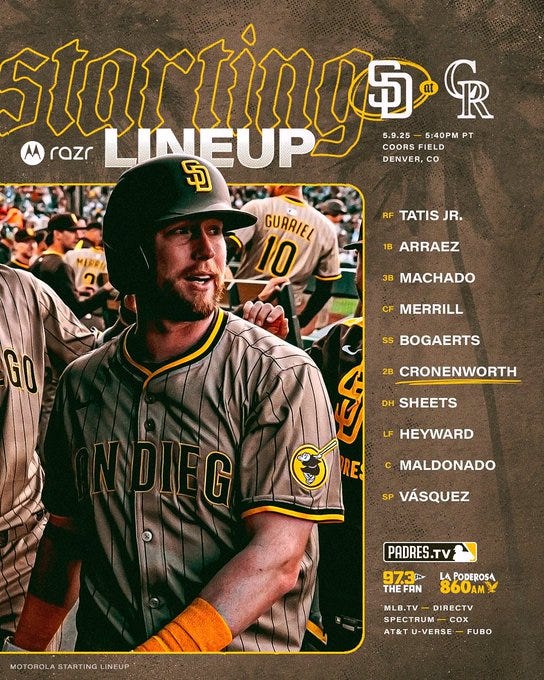

Game one was a typical Coors Field game with enormous amounts of offense from both sides. It was also the first game this season the team put forth a truly coherent lineup top to bottom:

The return of Jake Cronenworth lengthens the lineup considerably. The team would score early and often, jumping ahead 5-1 in the second inning on a pair of doubles from Jackson Merrill and Gavin Sheets:

The double from Merrill was 107.2 MPH line drive to the opposite field on a pitch very low in the strike zone. Merrill has special bat to ball skills and has developed terrific bat speed to go with it. The lineup is very different with him in it.

Randy Vasquez started the game for the Padres. He was unusually effective getting eight whiffs and striking out five on the way to six innings pitched and only two earned runs on a pair of solo home runs. It’s hard to say why he was so successful. And it’s likely some of it is the competition. He did induce a lot of weak contact. And he prevented at least one run by fielding his position well. He got good mileage out of his cutter, a pitch that tends to keep its shape better in the high altitude than others:

Vasquez continues to have the strangest year of any Padres pitcher. He’s pitching to career bests in hard hit rate, average exit velocity, home run rate, and ground ball rate:

But he’s also putting up career worsts in strikeout rate, walk rate, and his FIP, WHIP, and SO/BB ratios are all signaling risk:

At this point Vasquez’ good outings feel like a game of chance played with a pair of loaded dice. It’s very hard to attribute his success to a particular skill he’s displaying, but it’s getting harder to believe that his success is just luck. He’s had very good outcomes on the whole this season. We just don’t know why. If we can figure out where his success is coming from we’ll certainly write that up.

The Padres were leading 12-2 in the 7th when Mike Shildt pulled Fernando Tatis, Manny Machado, and Xander Bogaerts. In an unsurprising turn of events the Rockies then outscored the Padres 7-1 over the final three innings requiring Robert Suarez to come in for the final two outs to get the save. This is a typical Coors Field game. It’s very optimistic to pull the starters before the final out in Colorado.

Game 2

The Padres started game 2 with something that’s been sorely missing: slugging. A five run outburst was capped by Gavin Sheets taking a really excellent at bat with a runner on third and two outs. After two poorly executed breaking balls in the dirt from pitcher Bradley Blalock, the count was 2-0, the quintessential hitter’s count. Watch the body language from Sheets on all three pitches, especially the 2-0 count:

He was ready to hit on 2-0 but not the slightest bit tempted by a pitch that was in the strike zone. That’s because it was on the outer half of the plate, and Sheets was in a three true outcomes (TTO) approach. The TTO approach is the best run maximizing approach to hitting over the long run. It can be summarized like this:

TTO-heavy hitters generally tend to follow one basic plan of attack at the plate: wait for a specific pitch you think you can hit 450 feet, take the pitches you can’t put a good swing on, and whenever you do get a pitch you can handle, swing hard.

He’s only looking for a pitch he can drive 450 feet. He’s honed in on the middle half of the plate and ignoring anything outside that zone. And Mark Grant noticed this in real time, listen to his impeccable analysis:

Grant is an entertainer, but he knows ball, and he can pick up on seemingly random events that are not random. There was nothing random about Sheets’ 2-0 take. He’d narrowed the strike zone in his mind to only the part of the zone that would let him get to his light-tower power. And this is something that’s been missing from the Padres offensive approach, largely because of an early season IL cataclysm. There are unquestionably specific situations in games where sacrificing power for a greater chance at contact can be a good risk tradeoff. And the Padres seem to be good at picking up on this. But you don’t want to over-index on small ball and contact hitting in times when it’s not appropriate. And in the first inning of a game at Coors Field it is never appropriate to play small ball or sacrifice power for contact (keep that thought in mind when we get to game 3). Because in Coors Field you can never know how many runs you need to win the game. And when it’s the case that you either don’t know how many runs you need to win, or you know that you will need a lot of runs to win, that’s the time to slug. Because slugging maximizes run scoring over the long term. It was refreshing to see an at bat where that was very clearly the intention.

The Padres would add runs in the 2nd and 3rd through good hitting and execution, including this mammoth home run from Jake Cronenworth:

This was 109.1 MPH off the bat. Cronenworth looks healthy. And his presence back in the lineup is big. He’s a genuinely plus hitter off right handed pitching.

The Padres would continue to run up the score adding runs in the 4th and the 5th with a little help from the Coors Field effect:

Those balls weren’t hit poorly, especially Heyward’s 101.9 MPH exit velocity. But those also aren’t home run swings, and balls hit with those ballistics don’t travel as far at normal altitudes.

The Padres would keep putting baserunners on, and later in the 5th Tatis got good launch on a three-run home run to bring the score to 19-0:

Since getting hit on the forearm in the first game of the road trip Tatis has been in a launch angle slump. He’s hit plenty of balls hard over that span, but does not have a lot of slug to show for it. These are all 15 hard hit (EV >95) batted balls for Tatis (average EV 102.3 MPH) since he was hit in Pittsburgh:

There’s no way to prove a connection between a badly bruised forearm and an average launch angle on hard hits since then of 3.4 degrees. It could be something else entirely. But the failure to launch has undoubtedly been another source of the team’s lack of slugging recently. Prior to the hit-by-pitch on May 2nd, Tatis had been averaging a 104 MPH exit velocity on hard hit balls, and an average launch angle of 9 degrees. Nothing in the game film or from the team has suggested Tatis is doing anything deliberate to end up with so many hard hit balls with diminutive launch angles. He’s added back a leg kick to his batting stance, which would seem to be a mechanical change to try to get to more power. And this what you want to see from a hitter like Tatis. Tatis has the most raw power on the team. You want him trying to get big exit velocities and healthy launch angles most of the time. You only want a hitter like that switching to a contact hitting mode when the game calls for it. So we hope it’s just a lingering effect of not being physically back to 100% yet, because that should improve. We saw Manny Machado struggle with failure to launch when he was still recovering from offseason surgery last year, and he eventually found his way back to healthy launch angles by the end of the season.

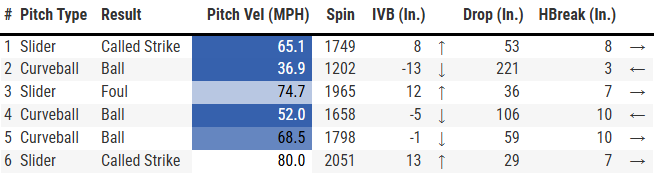

When the game was truly out of hand the Rockies brought in Jacob Stallings to mop up some innings. This led to a truly hilarious at bat in which Stallings pulled out every trick in the book to get Elias Diaz including an eephus pitch with 221 inches of vertical break (drop), a quick pitch, a submarine slider, and finally an 80 MPH heater that probably looked like something from the Ryan Express after all that junk:

The at bat is worth a watch:

Stallings tried the eephus pitch with Gavin Sheets, but Sheets stayed back on it somehow.

Actually an impressive piece of hitting.

While the Padres were busy scoring runs on their way to a 21-0 lead, Stephen Kolek was making his second ever big league start, and shoving. Kolek’s secret to success is pretty evident. Similar to last year, and to his first start in Pittsburgh, Kolek was giving up plenty of hard contact. But he was limiting the Rockies ability to get to productive launch angles, and this is a key to success in Coors Field:

Only Mickey Moniak’s lineout was in the dangerous 20-32 degree launch angle window, and it wasn’t hit hard enough to be a line drive home run.

Kolek has been an extreme ground ball pitcher at every level, and indeed this is likely what drove the team to give him a precious roster spot all last season as a rule V draft pick. Ground ball heavy pitchers with the stamina to go multiple innings can be valuable in the back of a rotation or in long relief.

It’s interesting to consider one aspect about pitching in Coors Field that would seem to directly influence ground ball pitchers like Kolek. Look at his pitch shapes in Coors compared to his averages:

His pitches really didn’t change shape that much. The most he lost from season averages was the -3 inches of horizontal break on his sinker, but he maintained the steep vertical drop of the pitch, including throwing one sinker with 29 inches of vertical drop. In the thin air of the Rocky Mountains there is far less Magnus effect to get movement on pitches from spin and differences in the surrounding air speed. This can affect pitchers very differently, but not all pitches depend heavily on Magnus force to be effective. Kolek throws an arsenal that is very heavily downward breaking. Even his 4-Seam fastball has a lot of downward vertical break for that pitch type, because it does not have much upward induced vertical break. In Coors Kolek saw a 2 extra inches of drop on his cutter and slider, arguably improving that aspect of the pitch shape, while also seeing an increase in the horizontal break. The horizontal break on the cutter isn’t highly dependent on Magnus effect, and Kolek throws an unusual slider that has very little horizontal break and almost all downward break. Pitching well in Coors has been an interminable mystery, and when pitchers have had success it has often been attributed to luck. But maybe with the right arsenal it’s possible to have certain pitches play up in Coors. Or at least not play down.

Kolek would remarkably go the distance, completing a 21-0 shutout in Coors Field and joining some elite company:

It’s very revealing to juxtapose the success Kolek had with the rough outing that Nick Pivetta in game 3.

Game 3

Game 3 had the feel of an unfocused effort. There’s no way to know whether it was in fact an unserious effort or if that was just the vibe it gave off. But pointing towards an unfocused effort was this decision in the first inning by Luis Arraez:

As we discussed above, there is a time for small ball. And that time is never in the first inning in Colorado. There is definitely a time to show bunt to draw in the third baseman, and perhaps that’s what Arraez was actually trying to do here:

But that pitch was so high and outside that he could’ve showed bunt and easily pulled the bat back in time. A feigned bunt is just as likely to draw in the third baseman. Instead he poked at a pitch he had absolutely no chance at putting in play and gave the pitcher a free strike. Coors field has deep dimensions but the ball travels much further than at sea level. Even a hitter like Arraez can slug. Bunting in Coors is bad process, even when it works.

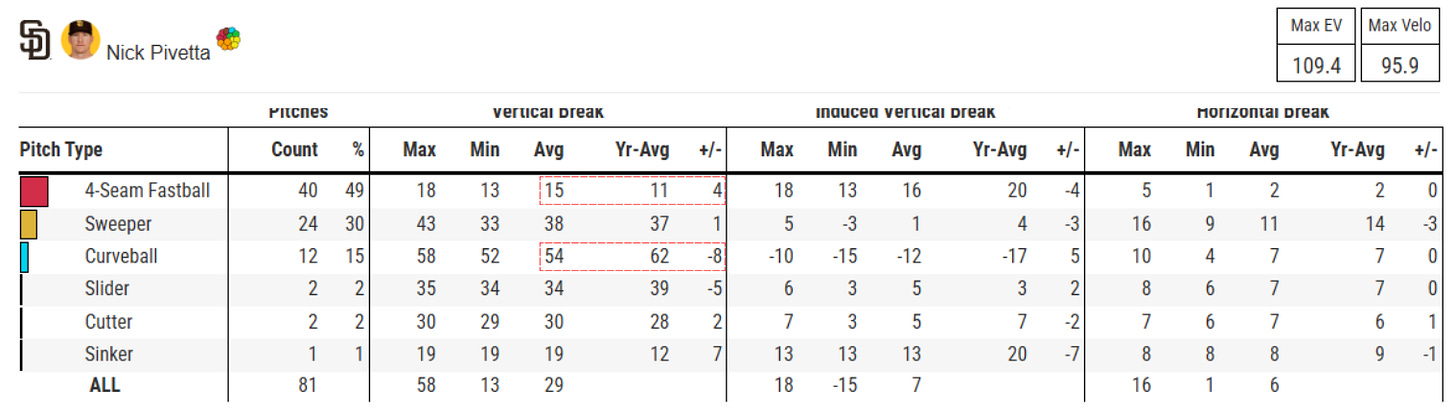

The Padres offense would go on to an anemic 3 run output on the day, an unacceptable sum at Coors against a Rockies team that is this bad. But the real story on Sunday was Nick Pivetta’s performance. And it doesn’t have to be a long story. Start by looking at Nick Pivetta’s pitch shapes in Coors Sunday:

Pivetta and Kolek are very different pitchers. While Kolek is groundball heavy and gives up a lot of contact, Pivetta is very fly ball prone and makes his living trying to limit contact by striking hitters out altogether. He does this with a four-seem fastball with some of the best ride (induced vertical [upward] break) in the league, and a hammer curveball. But as you can see above, both of those pitches are just neutered by playing in Coors. The four-seam fastball had on average 4 inches less induced vertical break on it, and that led to more downward drop on Pivetta’s 4-seamer. That’s a bad thing for Pivetta because he tries to get a lot of ride on his fastball to get hitters to swing under it for whiffs or popups. He’s fond of starting at bats with 4-seamer’s at the top edge of the zone:

But from his first pitch of the day on Sunday you could see the shape was off:

A few inches less ride made that pitch a meatball and Brenton Doyle was all over it.

The curveball shape was even more diminished, with about 8 inches less drop than usual. And these extra inches matter: Pivetta will often try to devastate a left handed batter with a ridiculously steep curveball. But it just doesn’t move as much to hitters in Coors:

Contrast this curveball with one he threw in Petco the last time the Rockies were in town, both to left handed hitters:

Pivetta had a very hard time finishing off batters who kept being able to make contact and keep rallies going, including this piece of hitting by Mickey Moniak:

This curve had only 52 inches of drop, 10 inches less than the 62 inches of break Pivetta usually enjoys:

Pivetta gave up plenty of hard contact, but unlike Kolek, he could not keep hitters from getting to healthy launch angles:

Pivetta would give up six earned runs in only four innings of work. But what’s interesting is despite how bad his outing was, you could argue it was his best ever at Coors Field:

And although this was only Pivetta’s fourth start at Coors, a small sample size, there is a physiologic explanation for why he is very likely to struggle in Coors field, even when facing a bedraggled Rockies lineup that may end up being one of the worst of all-time. The very thing that makes Pivetta’s pitches special, their great movement largely induced by the magnus effect, is neutered in Coors Field.

The Padres will be back in Colorado September 5th-7th, during a stretch of the season that rosters expand to 28 players. This raises the question of whether the Padres might purposefully skip Pivetta’s start in favor of an opener which might be a AAA callup with a groundball heavy profile. Especially if the playoff race is still close at that point.

The Padres finished the road trip 6-3 and are 25-14 on the year. A sweep would have been nice but was not a prerequisite to call the road trip successful. And although it was Coors Field, the slugging the lineup showed is likely not all empty calories mile-high stat padding. The lineup is getting near full strength and is vastly improved with the returns of Merrill and Cronenworth.

The Padres will play the Angels Monday, the opening game of a home stand. The Angels were the second most vexing bad team last year after the Rockies. But at least these games will be played at sea level.

I think there is a very easy way for Shildt to explain to Pivetta why he shouldnt start in September at Coors. The data is undeniable, and it's not a knock on Pivetta, it's just physics. Heres to hoping everyone can do what's best for the team, instead of capitulating to the size of the player's paycheck. All things considered it was a great road trip! I got to be in the stands when Tatis stole home in Pittsburgh, and also sat through the rain for their comeback against the Yanks on Monday. It was a blast! Love this team, and so stoked to see Merrill back in CF.

I’d like to get your thoughts on moving Merrill to 2nd in the order, Arraez to 4th. I’d like to see it because it might get Merrill a couple extra at bats plus Arraez is more likely to come up with a runner on base at 4.