Fernando Tatis Jr. had a transcendent March/April that had him in deserved early MVP discussions with a tremendous 1.021 OPS and 8 home runs with a tidy 14.9% strikeout rate. But May was the worst month of his career:

Tatis is 26 years old, in his athletic prime, and in his six years in the league never had a month with worse offensive production than the horrid .184/.257/.369 slash line good for a nearly replacement level .626 OPS. His strikeout rate ballooned to 22.1%. Drastic performance degradation like this should raise the consideration of outlier performance. Bad luck can explain any stretch of performance no matter how outlandish, but before chalking it up to that it’s worth looking for anything that may have been different about May. And one thing stands out:

This turned out to be an injury Tatis was able to play through. But there are a few things that seem to worth another look when revisiting this now. First, the size and location of the bruising to his left forearm:

This is a gigantic area of soft tissue trauma directly overlying the bed of the extensor muscles of the wrist. It’s not unreasonable to think this could affect a hitter’s swing mechanics, even if he was able to play through the injury. This necessarily has to be speculative. While applied biomechanics has revolutionized the pitching world, comparatively little progress has been seen on the hitting side. Baseball Savant only released the full bat tracking suite a month ago. And so biomechanical understanding of what affects swing performance is still nascent in baseball. But in other sports like golf and cricket there is an abundant literature on swing biomechanics. And wrist extensor weakness or instability has demonstrable effects on golf swing efficiency through motion tracking. And it’s easy to speculate how a left arm wrist extensor injury might affect a right handed batter’s swing: the left arm in a right-handed batter's swing functions as the lead arm, crucial for guiding the bat path, setting the attack angle, and initiating the swing arc. All of these actions require careful control of wrist extensors. Could pain, swelling, or reduced mobility in lead arm extensor muscles cause a swing to flatten due to premature wrist flexion, or inability to maintain extension through contact? We took a look to see if anything is out of the ordinary pre and post forearm injury from the Mitch Keller hit-by-pitch which occurred May 2nd.

At first glance there weren’t any obvious swing tendency changes:

In fact, Tatis’ bat speed, attack angle, and ideal attack angle percentage actually increased after the hit-by-pitch. These are changes you would expect from a player hunting for, and likely to get, more barrels and fly balls. And it’s fascinating to look at the actual batted ball profile from before and after the hit-by-pitch. Here are Tatis’ batted ball ratio’s from opening day to May 2nd:

While Tatis was putting up his torrid .345/.419/.602 slash line in March/April he had an extremely high ground ball rate, but a miniscule pop-up (IFFB = Infield Fly Ball) rate, with modest line-drive and fly ball rates.

Look what happened from May 3rd to May 31st:

Despite what the eye test might’ve suggested, while Tatis was having the worst slump of his life his ground ball rate went down and his flyball rate skyrocketed. His pop-up rate also increased, and he hit almost no line drives. He had a much higher average launch angle. His Exit velocity took a small dip (which might be expected with an enormous jump in average launch angle), and even after the dip his average exit velocity was in the league’s 95th percentile.

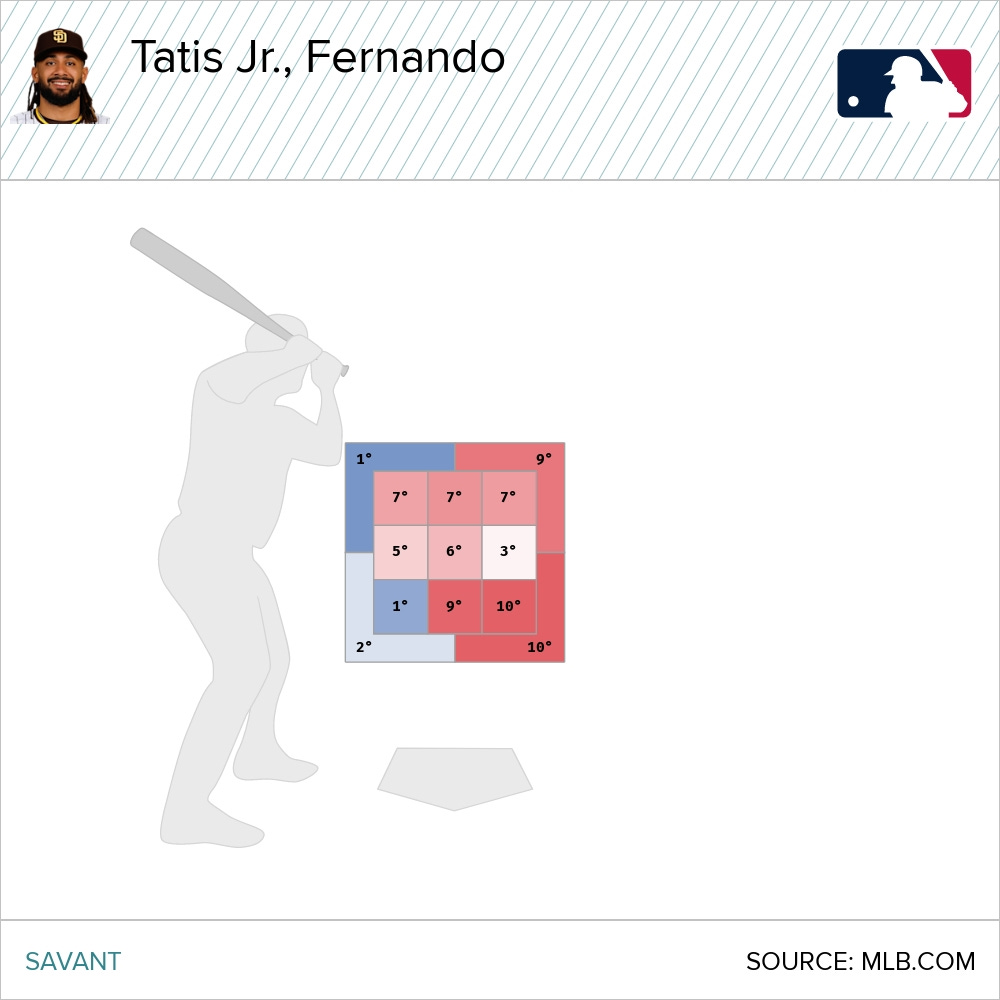

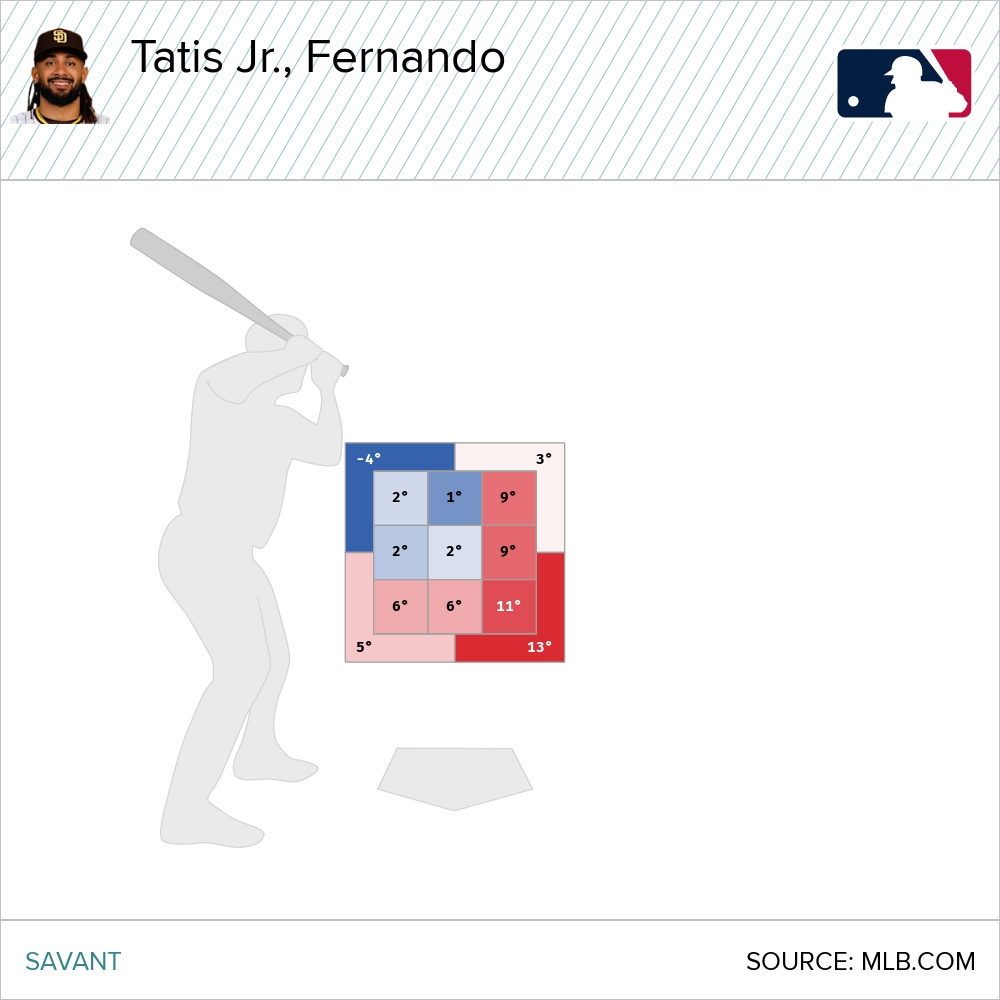

But the swing shapes before and after the hit-by-pitch weren’t that different, right? Maybe not when looking at surface level averages, but take a look at the average attack angle of the swings Tatis took before and after the hit-by-pitch when broken down by zone. Here was his swing path from opening day to May 2nd:

Ideal attack angle is considered between 5-20 degrees. You can see that for most of the zone, especially up in the zone and on the inner half Tatis was averaging healthy attack angles. Now compare to his performance from May 3rd to May 31st:

This is drastically different, even though the overall averages for all zones combined were fairly similar pre and post hit-by-pitch. It’s only been a third of the season, which is firmly in the small-sample-size-theater district, but this is the profile of a hitter struggling to put good swings on pitches in the heart of the zone. Indeed, here is Tatis’ spray chart on pitches located middle-middle from May 3rd to May 31st:

But that’s not everything. Because even when Tatis has put a good swing path on a pitch in the heart of the zone recently he hasn’t been having great success:

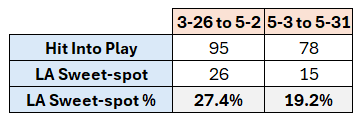

This swing path had an ideal 13 degree attack angle 6 degrees to the pull side, but still ended up as a groundball. And this is what it comes down to: productive hitting doesn’t come from hitting the ball hard, or a swing path designed to hit it in the air, it comes from hitting the ball well — meaning a combination of sufficient exit velocity and a healthy launch angle. Baseball Savant’s Squared-Up percentage metric might sound like it captures this, but it is a metric that only considers exit velocity. There’s a different Statcast metric that shines above all others when predicting whether a ball was hit well, irrespective of whether it was hit hard, or in the air, pulled or opposite field. Take a look at Tatis’ performance in the Statcast metric Launch Angle Sweet-spot:

The launch angle sweet spot is between 8 and 32 degrees, and is so named because hits with this initial trajectory are incredibly productive. In 2025 all batted balls within the launch angle sweet spot have a batting average of .573/.565/1.020, good for an OPS of 1.585. Even if you limit it to soft hits with 70-75 MPH exit velocity, balls hit into play in the launch angle sweet spot have a ridiculous .659/.657/.703 slash line over the Statcast era. For exit velocities over 95 MPH the OPS jumps to 2.014. It’s a meaningful metric, and Tatis has dropped to the 2nd percentile in the league here. And it’s revealing to look at Tatis' performance before and after suffering the contusion to the extensor compartment:

It looks like Tatis’ abysmal numbers in May stem from failing to hit the ball well even as he continued to hit it hard and in the air. He wasn’t getting the ball into the launch angle sweet spot nearly as frequently. And it’s when you parse this down one more layer by examining how many of the balls hit into the launch angle sweet-spot were also hit hard that you see the void of productivity taking shape:

What we can say is that Tatis showed several signs of inconsistency in May including very different swing paths compared to the first month of the season. And even when he put a got to a good swing path, he was rarely hitting the ball well. There’s no way to know if Tatis’ swing path disparity and inability to hit the ball well during May is due to sustaining a contusion to the extensor compartment of his forearm. But it’s one explanation that has some plausibility. And strangely, it carries a pretty favorable prognosis compared with other potential explanations (deliberate swing changes, catastrophic deterioration of skill, loss of approach etc.). Nothing is monocausal, and it’s likely that a combination of factors explain the slump. But injury to the extensor compartment of the lead arm of a hitter would be expected to lead to a flattening of the attack angle similar to how it would a golf swing. It’s something to consider. And this has some important implications for how the team makes decisions over the next two months.

Unofficial Milestone

The Padres completed an unofficial milestone Sunday. For the remainder of the first half of the season there will be no easy series. Every opponent currently has a winning record, positive run differential, or both. Save one: the Arizona Diamondbacks (currently 28-31 with -10 run differential). And it would be foolish to think those will be easy games. The ‘soft’ part of the schedule is over. Through the first 57 games the Padres sit at 33-24, a ~93 win pace that would match last season’s effort. And the team just finished a month in which it became undeniably clear that the roster is flawed. If they hope to compete throughout the season roster improvements, especially in left field, will be needed. This was only accentuated when on Sunday, the experiment of having Gavin Sheets play left field went terribly wrong:

Gavin Sheets has been a tremendous success story in the early season as a hitter, but there is precious little evidence that he can play a regular left field. That doesn’t mean it was wrong to try him there. If Sheets were able to hold down left field that would have been a major development that freed up assets to improve the other weaknesses. But given there was little reason to think the experiment was going to be successful beforehand, it shouldn’t take too much confirmatory evidence for the team to move on. An injury scare should put this experiment to bed. Sheets should recover, but it’s fair to say that this was a near miss. Mike Shildt’s post-game update sounded like the EMS run sheet at a trauma center:

What shouldn’t be missed is just how far below league average the production from left field has been, and projects to be, without structural change:

Major league average OPS from left field is .710. The Padres cumulative .525 OPS from left field is farther below league average than Fernando Tatis Jr’s .820 OPS is above average. Another way of thinking about this is the Padres gain as much upside from filling left field with an average major leaguer (+.185 OPS) as they would from upgrading from Xander Bogaerts .664 OPS at shortstop to Francisco Lindor’s .846 (+.182 OPS).

The problem is most league average left fielders are on rosters of teams looking to contend themselves. The natural fit would be for a team clearly out of contention this early in the season, with a veteran in the later stage of their career, with a very cheap contract. Something like the White Sox tandem of Austin Slater and Mike Tauchman wouldn’t make waves in the news cycle but each has a high likelihood of providing league average production. Slater is heavily platoon dependent but has raked against left handed pitching his entire career (.797 OPS). Tauchman has shown remarkably little platoon variability in his career (.733 OPS vs R/L), and has always been able to draw walks at a high rate. Trading for both would put a competent hitter in left field with another coming off the bench every night. These players won’t be free, but are almost certainly available without trading away blue chip talent. But is even a modest investment of future value for present value justified? Because if the stars can’t perform, improvement around the margin is only going to go to waste. How much to invest in such an improvement should be based on what the team’s expectations are with its star players, and none is more important than Tatis.

I hear you on Slater and Tauchman. Curious what you think of the fit with the Duran rumors (or Robert Jr). AJ always seems like more of a 'big swing' guy.

Pretty compelling analysis on Tatis. Just the timing of the injury to the shift in numbers seems more than coincidental. If so, wondering what changes that. A month seems a long time for contusion to still be hampering him, given they let him play. Whatever the cause, I want my old Tatis back.

We dodged a bullet last year in LF with Profar's career season. That bullet now lodged in our abdomen with more coming. Preller found Solano and Peralta last year, but maybe too much to ask for catching lightening in a bottle again, but need serviceable LF. The types you describe seem a reasonable solution but not sure what our system can support, even for aging, mediocre talent.