Peter Seidler was not just another owner of a major sports franchise. Seidler was that all too rare species of business owner whose fidelity to civic duty didn’t take a backseat to the interests of short-term profit. By daring to take the San Diego Padres to vertiginous and unprecedented heights in payroll for a team of its size, Seidler galvanized an overlooked, oft-dismissed sports market by giving them something no previous ownership group had ever tendered: hope of sustained excellence. His loss to all of us who love this city and this team is immeasurable.

Beautiful eulogies have been written for Peter Seidler this week. We especially recommend the Kept Faith’s articles by Dallas McLaughlin and Mark Wilkins. What we are writing is very much an homage, but one of inquiry. That is: We want to inquire about Seidler’s vision for the Padres, because we think that vision deserves tribute in addition to remembrances of the man himself.

In game theory, there is one “game” that’s more famous than the rest: the prisoners’ dilemma. The game was formalized by Albert Tucker, who described it this way:

Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of speaking to or exchanging messages with the other. Prosecutors don't have enough evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge. They plan to sentence both to a year in prison on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the prosecutors offer each prisoner a bargain: If he testifies against his partner, he will go free while the partner will get three years in prison on the main charge.

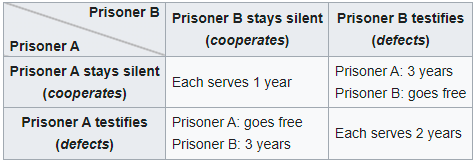

The different possible outcomes for prisoners A and B:

If A and B both remain silent, they will each serve one year in prison.

If A testifies against B but B remains silent, A will be set free while B serves three years in prison (and vice versa)

If A and B testify against each other, they will each serve two years.

Most examples of the prisoners’ dilemma include a payoff matrix that looks like this:

The prisoners’ dilemma is fascinating because the rational decision for the individual, to betray the other, leads to an objectively worse cumulative outcome: they both get two years in prison versus only one if the prisoners had acted irrationally and remained silent. Once both prisoners recognize that betraying the other is the optimal individual strategy, there is nothing they can do unilaterally to improve their fortunes. They both end up in the “betrayal” square, a place that game theorists call the “Nash equilibrium”.

Baseball’s Prisoners’ Dilemma

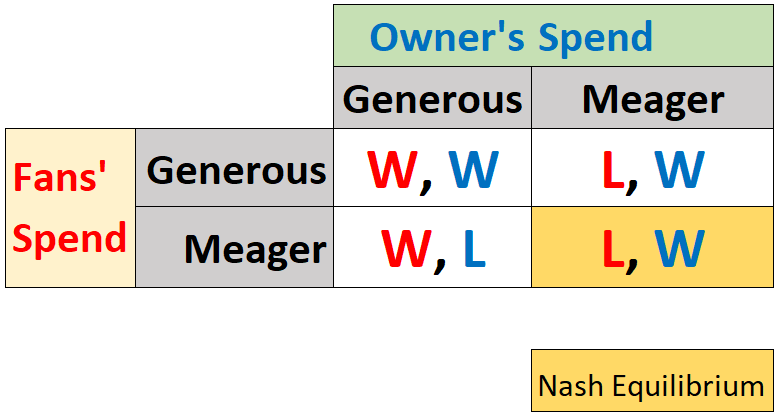

Something similar to the prisoner’s dilemma exists between a baseball team’s ownership and its fan base. This stems from the fact that Major League Baseball is not truly a competitive industry. Franchises exist as geographic monopolies; the Savannah Bananas are a professional baseball team, but they are not a credible threat to the Atlanta Braves any more than the Harlem Globetrotters are a threat to the New York Knicks. The owner of a major league baseball team does not face the same pressure to put forth a superior product as a business in a truly competitive industry might. Revenue sharing combined with the forces of geographic monopoly and the resultant captive fanbases ensures that even the teams with the most mediocre on-field product tend to be profitable. Even when chronic underinvesting leads to fanbase attrition and dwindling gate revenues, a team owner can seek a new geographic monopoly by moving to a different city. Often, this move comes with hundreds of millions of dollars of public funding and infrastructure spending. Within this framework, a Nash equilibrium develops in which owners are encouraged to spend meagerly, because they make money either way. This can have the effect of pushing fans to reign in their spending, as well, because the team is less likely to be good. The payoff matrix might look something like this:

“Winning” and “losing” here are only relative to the other states. Neither party can take unilateral action that improves its position. Through this lens, the only losing move for an Owner would be a generous spend that was not reciprocated.

More Than Winning

Here, it’s important to note that ‘meager’ spending by owners does not mean giving up on winning entirely. A team can (and surely will) hope to win even while spending meagerly. Moneyball, the most influential book about baseball ever written, focused entirely on this exact concept. It’s possible to win even with meager spending. The Diamondbacks came within three wins of a World Series title with one of the lower payrolls in the league. This, from an owner’s perspective, adds to the gravitational pull towards constrained spending; after all, if you can win with a small budget, then you’re having your cake and eating it too, right?

There is a school of thought that argues that an owner’s responsibility to fans is simply to pursue a winning product on the field. If that can be done within the constraints of meager spending, then the job is done… but surely there’s more to it than that. Jerry DiPoto was pilloried for his comments about the Mariners’ strategy to pursue being consistently good without ever going all-in to try to win in the short term. Perhaps DiPoto’s main mistake was simply saying the quiet part out loud. But if winning was all that mattered to fans, then there would not have been an uproar after such candid comments. But fans were incensed that DiPoto seemed to be content with a good-but-not-great product, and letting the owners off the hook for more spending. It seems that how a team pursues winning does matter.

This makes sense. Baseball, after all, is more than a bunch of box scores and Fangraphs printouts: It’s a relationship. Fans get attached to their team and to the players. Being able to buy a jersey of a player you love and know that that player is going to be on your team a year from now matters. Over time, a team identity develops. A successful team becomes part of a city’s social fabric. Over the past twenty years, the Oakland A’s built many successful rosters, multiple division titles, and were in the playoffs many times. But there was constant churn. They never re-signed their stars. They never made a splash in the free agent market. The A’s teams were etch-a-sketch teams: At the end of the year, there would be a shake up that totally erased what was there. And Thursday, the league voted unanimously to approve a move to Las Vegas. The owners have moved on to a new geographic monopoly.

It’s hard to argue that there is any inherent moral valence at work here; these are just the rules of the larger game of the baseball business. And it was against this backdrop that Peter Seidler pursued a different vision. Seidler didn’t succumb to the prisoners’ dilemma. Seidler’s vision didn’t start with a four. What motivated Seidler is hard to know. His generosity was legendary. But perhaps chalking his actions up to pure generosity sells his vision short. Seidler was a financial genius who spoke passionately about a future for the Padres that would exist well past his years on Earth. This was not the vision of a person who threw money around without purpose. We wonder if he didn’t know something about the prisoner’s dilemma, and the Nash equilibria we all face as we go through life. Something that can be easily missed…

Uncommon Vision

The prisoner’s dilemma has a Nash equilibrium, that of defecting from the counterparty without loyalty or the expectation of any in return. Yet, strangely, when Robert Axelrod set up a tournament to test the optimal strategy for winning multiple games of prisoner’s dilemma in a row where players had memory of what had occurred in previous rounds, an entirely different dominant strategy emerged:

Surprisingly, there is a single property which distinguishes the relatively high-scoring entries from the relatively low-scoring entries. This is the property of being nice, which is to say never being the first to defect.

The optimal strategy, called TIT FOR TAT, starts with a cooperative choice. That is: The player does not defect in the first round. After the first round, the player does whatever the other party did in the previous round. When many rounds of the prisoner’s dilemma are played, cooperation becomes more possible than it was in a single round.

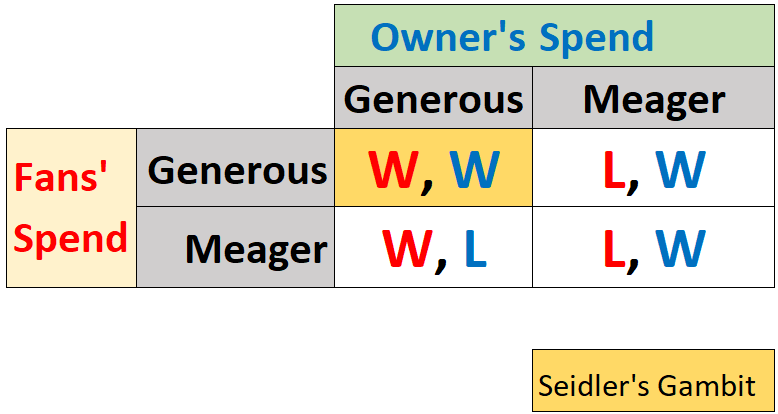

The equivalent to TIT FOR TAT in the baseball world would be for an owner’s first move to be to spend beyond what the fanbase expects. This was essentially Seidler’s gambit. Seidler was basically trying to create a situation in which he and the fans ended up in the top-left square::

Seidler chose to pursue a generous spend on the team, which meant that an actual financial risk was incurred. He could have played it safe and gone small – that’s not what he did. Instead, he tried to see if the Padres could enter a virtuous cycle in which high spending would produce a good team that would grow the fanbase and enable more spending. A perpetual motion machine… There are real world examples of teams shedding their geographic constraints to pursue such a virtuous cycle. They’re not common, but they’re possible. Manchester United (a team whose reach extends far beyond Manchester) and a handful of others come to mind.

It’s fair to wonder why the cooperative strategy isn’t more common if it’s the dominant strategy in the long term. The answer is probably because we’re human and we live in the real world. That first step is a doozy: turning your back on guaranteed monopoly profits, and risking millions of dollars in personal wealth, as well as that of equity partners, and having to cut through the friction of doubt and step beyond the path of least resistance all while under intense public scrutiny. Who among us wouldn’t wither under such a spotlight? Who can say they would choose the path through the heart of the jungle? We think Peter Seidler can say that. And we could assume that his big spending was simple generosity, simply trying to bring a title to San Diego, which – if true – would not be a bad thing! But it’s also possible that he was trying to ignite something even better, something that takes uncommon vision; he might have been trying to start that ever-elusive virtuous cycle.

Whether he was driven solely by generosity or by a pursuit of the flywheel of mutual growth, what Peter Seidler did for San Diego was transformative. And it must have been very hard. Even with his vast fortune, his charisma, his powerful role within the organization, there would have been untold obstacles in the path of a small market owner pursuing big market dreams. There were never any guarantees of success. He put his trust in the city and community. He acted on faith.

So we say thank you Papa Pete. Thank you for the faith you put in us. Thank you for the countless obstacles you fought against and overcame in pursuit of a beautiful dream. We don’t imagine for a second it could have been easy. We don’t imagine we would've been destined to succeed in the same endeavor. And we won’t forget.

We’ve been rooting for the Padres to win a World Series our whole lives, and now we have one more reason to root for them to one day make it to the Promised Land.

Great article. I don't think there is any doubt he was trying to create the virtuous circle and fans responded in-kind. It takes a strong leader to get other partners to get behind that vision and somehow, he did it. Remains to be seen if the subsequent controlling owner(s) will stay true to the vision.

Ultimately, continuing down this path will be determined by the next local TV / streaming contract, the Padres' ability to monetize Petco outside of baseball, real estate development in / around Petco, and the next MLB TV / streaming contract. Attendance at the Park and associated revenue is a limited by capacity at the Park and the elasticity of demand for tickets. Even a winning team can only charge so much. Have the Padres hit that point yet? I don't know. But it's hard to believe they can get too much more out of the fans, especially if the team is mediocre.

All that aside, Peter Seidler is a model owner. He loved the game. He loved the fans. He invested his heart, mind, soul and money into the franchise. It wasn't a bauble around his neck that he showed off to his friends at his villa in Hawaii or Laguna, etc. He gave the Friar Faithful something real to have faith in after years of abuse and neglect. More personally, he gave my family, particularly my son and me, many moments of joy and connection that we otherwise would not have had. And for that, I will always be grateful for Peter Seidler.

Of course Mr. Seidler's true motivations are impossible to know, but the possibility does exist that he wasn't placing faith in San Diegans to keep paying through the nose for tickets as much as he was making reckless bets to win a World Series before he died. Mr. Seidler never got his World Series ring, but the albatross contracts he tied around the neck of the Padres will keep tightening, in two instances for more than a decade. I wonder how Mr. Seidler's ownership will be viewed a few years from now?