Expected Value

And Risk Aversion

There will always be a feeling that in 2025 the Padres didn’t reach their full potential. That’s true in the literal sense. The team never featured all of its key players healthy, and in form, at the same time. September saw season ending injury to the best right handed power bat when Ramon Laureano broke a bone while swinging a bat, and Jason Adam ruptured a quad fielding a comebacker. This foreclosed on a full strength push in the postseason. Michael King and Jackson Merrill had lost seasons largely due to injury during the regular season. Fernando Tatis, Manny Machado, and Luis Arraez all languished through the worst slumps of their careers during 2025 for various reasons. But we can’t move past another reason the team didn’t reach its potential. A familiar reason. One thought to be vanquished. The Padres kept themselves from reaching their full potential because there was something that was elevated above winning. And with a month gone since the Padres season officially ended we still don’t know why. But the Padres aren’t the only team guilty of such flawed priority. The final game of the World Series, and subsequent debate that included several current and former players, demonstrates that flawed prioritization is very much a baseball-wide phenomenon.

Sliding Doors

In the bottom of the 9th inning in game seven of the World Series in Toronto, the Blue Jays and Dodgers were tied 4-4 with two on and one out. Yoshinobu Yamamoto was brought in to relieve Blake Snell, and hit Alejandro Kirk on the second pitch to load the bases. This started a sliding doors moment that will haunt Blue Jays fans the rest of their lives. The Dodgers made two defensive changes immediately. They moved the infield in, and they substituted Tommy Edman for Andy Pages in center field. Andy Pages was in the midst of having the worst offensive performance of any hitter with at least 50 at bats in the postseason in baseball history (a record he would later secure). But the Dodgers didn’t hesitate to bring in the stronger outfield arm with extreme fly ball hitter Daulton Varsho coming to the plate. Varsho had the second highest fly ball rate in baseball behind Cal Raleigh this season. A sacrifice fly would win the game. The game context meant the incremental upgrade in arm strength Pages offered had to be elevated above any other consideration.

For the Blue Jays scoring the runner from third meant winning the World Series. With only one out the run could score without needing a hit; either a fly ball or a ground ball could be good enough. Isaiah Kiner-Falefa (IKF) was on third having pinch run for the hobbled Bo Bichette earlier in the inning. And here, the Blue Jays elevated something above maximizing their chances at winning:

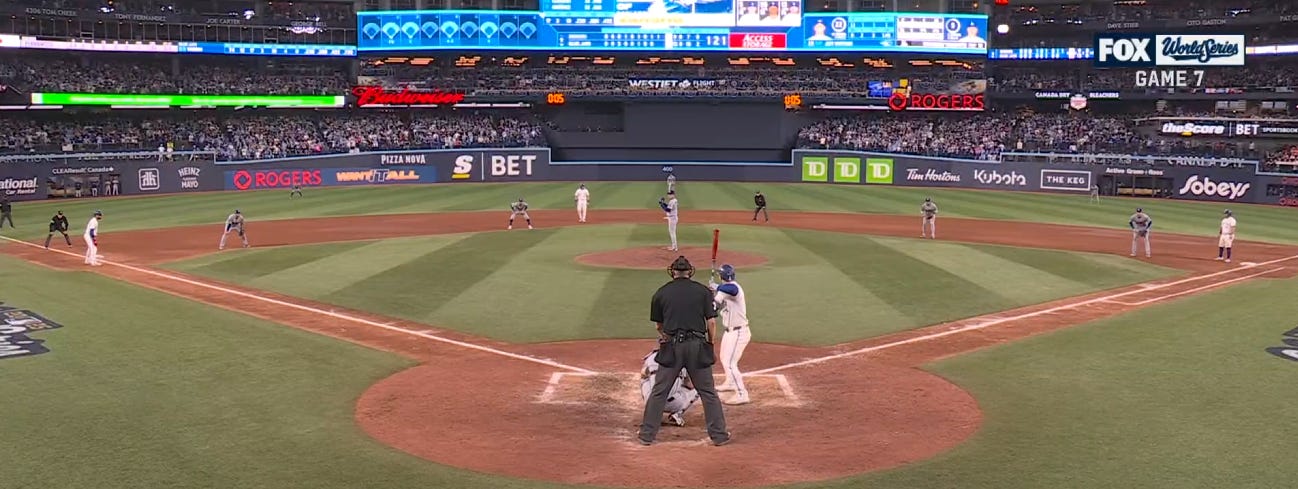

IKF took an extremely conservative lead off of third.

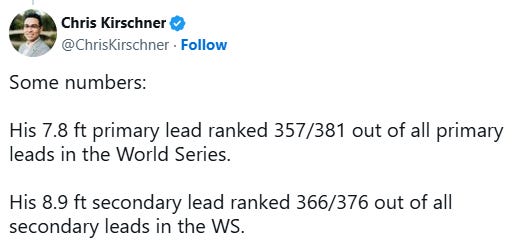

Runners are sometimes told to stray no further from the bag than the third baseman, but you can see that IKF is much closer to third than Max Muncy. Statcast showed IKF was only 7.8 feet from third base while Muncy was 15.2 feet from the bag.

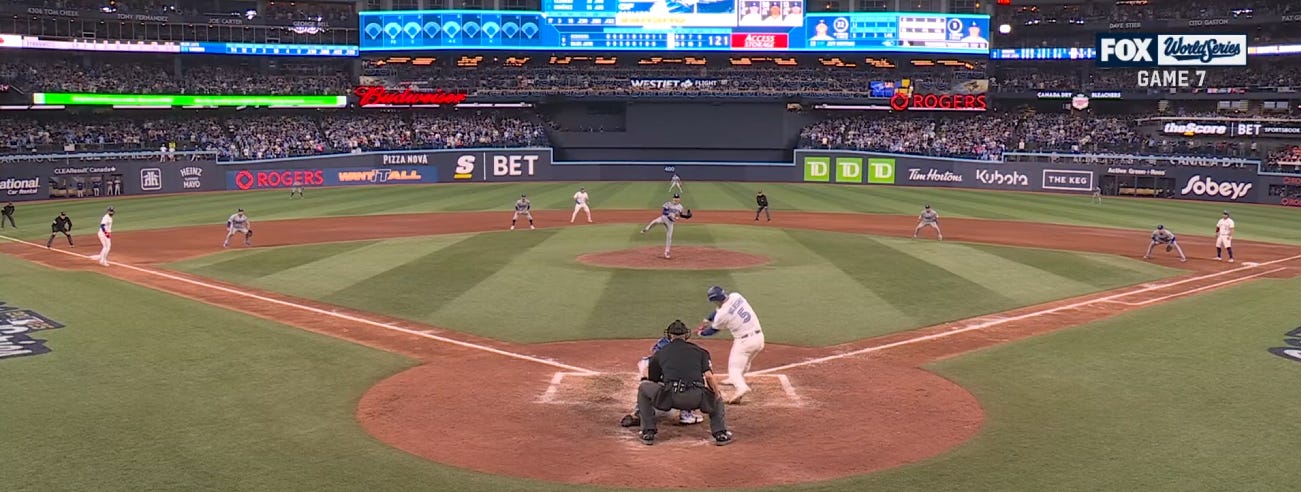

As the pitch to Varsho was delivered IKF took an even more conservative secondary lead, moving only one foot closer to home. He was 8.9 feet off third as the pitch was hit into play:

It mattered:

Miguel Rojas stumbled backward as he fielded the ball and could get nothing on the throw. Will Smith stretched to try to meet the slow throw, and in the process his foot momentarily came off the plate:

Had Smith made a clean catch IKF would have been out by ~four feet. But Smith’s lunge and momentary disengagement with the plate meant that IKF was ultimately out by a much slimmer margin:

This is the exact moment Smith’s cleat re-engages home plate:

It was devastatingly clear on replay that IKF taking a slightly more reasonable lead would have won the game, and the World Series, for the Blue Jays.

If IKF had touched home plate when Smith’s cleat was still disengaged the Blue Jays would be champions:

In the end the margin was inches.

IKF told reporters after the game he’d been coached to take a very conservative lead.

They told us to stay close to the base. They don’t want us to get doubled off in that situation with a hard line drive.

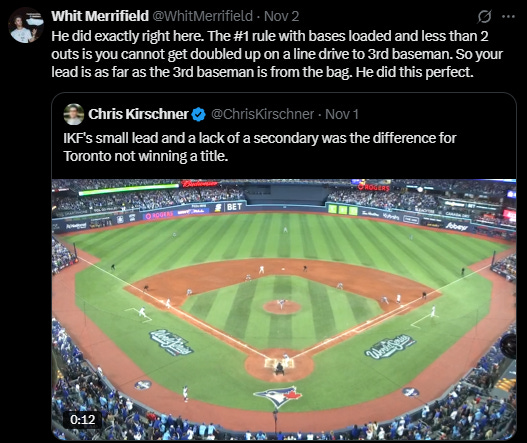

Many current and former players voiced the opinion that IKF’s extremely conservative lead was the correct play:

Merrifield and Turner, and the other major leaguers that chimed in are correct that IKF’s lead was playing it by the book. Baseball is an orthodoxy with sacred wisdom passed down generation after generation, and this is exactly what coaches say to do in this situation. The number one rule as a runner on base with the bases loaded and less than two outs is you cannot get doubled up on a line drive. The problem with this rule is that it’s wrong. The number one rule of every play of every game is to maximize the expected value of your decisions.

In little league or high school you don’t have the tools to do better than heuristics, rules of thumb that describe the direction of a shift in strategy but don’t include the fine tuning that separates playing it by the book from truly playing to win.

In the major leagues you have those tools. One team in game seven was using them to get every advantage possible. When Alejandro Kirk’s hit-by-pitch was confirmed on replay loading the bases, the substitution of Pages was instantaneous. The Dodgers understood the situation, and the hitter at the plate. Look at the positioning of the Dodgers defense:

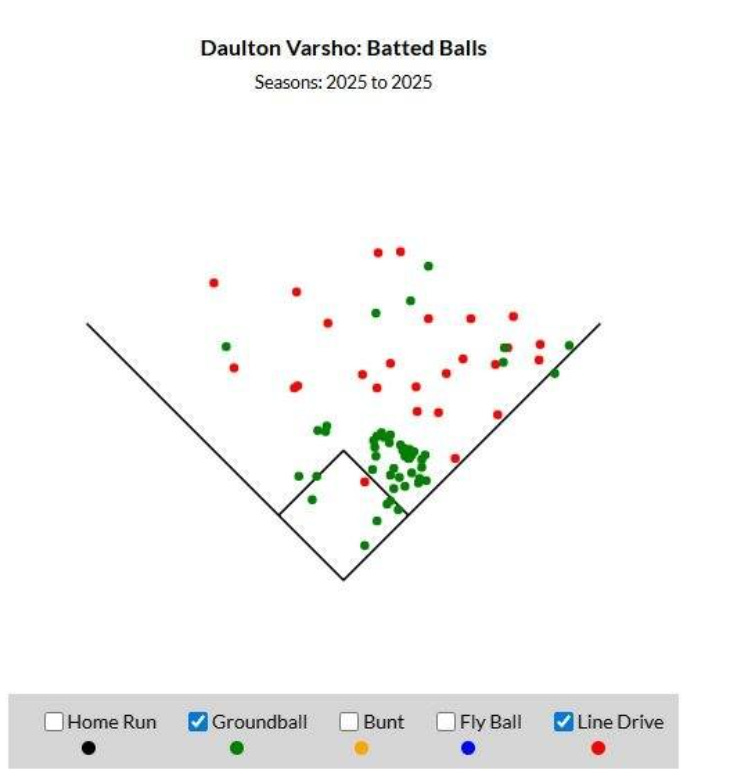

Here is the batted ball profile for line drives and ground balls for Varsho in 2025:

The Dodgers infielders are aligned perfectly with Varsho’s tendencies. He almost never hits grounders or line drives to the left side. In fact he hasn’t lined out to the third baseman all year. The defenders are aligned to maximize the expected value of their positioning. This is something the Dodgers obsess over. They don’t know what the next play is going to be, but they know which plays are most likely. First they positioned the infield by the book; they moved the infielders in. But then they fine tuned the alignment to the specific hitter at the plate. They played to win.

The Blue Jays and IKF didn’t. They played to avoid risk.

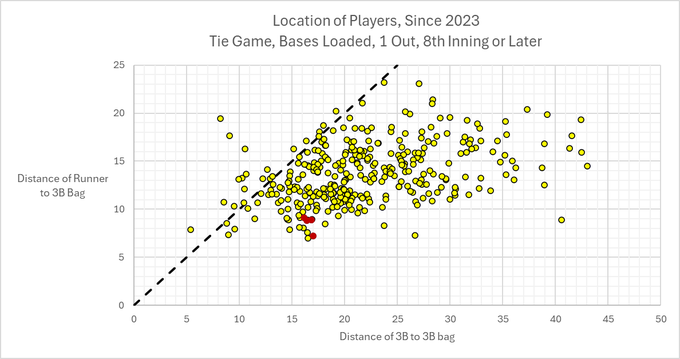

Tom Tango mapped every instance since 2023 of a runner on third base with the bases loaded in a tie game in the 8th inning or later. The four pitches while IKF was on third are mapped in red:

His lead was roughly two feet less than the average runner with a similarly positioned third baseman, a strategy that could only be explained by extreme risk aversion. But the wrong kind of risk aversion. Perhaps chastened by the way game six had ended, with Addison Barger being doubled off second after making an aggressive baserunning play, the Blue Jays let the pendulum swing to the opposite extreme. They elevated avoiding the risk of a very unlikely play above maximizing their chances to win. They chose a path with lower expected value. And it was the wrong decision even before it ended up mattering.

The Default State

The Dodgers pitched Shohei Ohtani, Tyler Glasnow, Blake Snell, and Yoshinobu Yamamoto in game seven. Four perennial Cy Young candidates. They are the only team in baseball that can do that. The Dodgers have a monopoly on acquiring the best players. If they want to sign Kyle Tucker and Kyle Schwarber this offseason they will. They can’t be beaten through talent acquisition. This is the default state of the league.

But baseball is not a deterministic sport. The NBA stood almost no chance when the 2016-17 Warriors added the best player in the league to a roster that went 73-9 the year before, but the Blue Jays team with two of its three best hitters playing injured just took the Dodgers to seven games, and smarter decision making would have seen them crowned champions. That’s the nature of baseball. The margin between the best teams in the league is slimmer. Surmountable.

A team can monopolize any single player, and hoard as much talent as their roster and IL spots can hold. But they can’t control the decisions their opponents make. They can only hope teams continue to blunder on the margins as the Blue Jays did when it mattered most.

Not Alone

There is no credible case to be made that the 2025 Padres maximized the expected value of the on-field decisions they made. 2025 will always be remembered as the season bunts were fetishized and batting titles were prized above winning. The Blue Jays proved they’re not alone in elevating priorities above winning. The two teams strayed from the path in very different ways. The Padres insisting on suboptimal lineup construction and old-timey offensive strategies was a willful act. The Blue Jays blunder was more insidious. They, and the many players rushing to defend IKF’s risk aversion, believed that their calculus was correct. They overlooked the fact that following philosophical rules of thumb is the opposite of calculation. In 2025 the availability of more sophisticated tools requires a different approach to winning. Fine tuning strategy beyond heuristics. Using contextual information in real time to sop up the inches that decide games. And abandoning ancient bromides.

In the end what separated the champions from the contenders wasn’t just the gap in talent, for in the season’s most critical moment that gap had been closed. But a breech remained in the understanding of expected value. Understanding the modern game.

The Default State will still be in place in 2026. The question is not whether the 2026 Dodgers will continue to outspend every other team in the league. The question is whether they will continue to out-think them. And in this matter every team in the league controls its own fate.

What a gut wrenching game. As a Padres diehard, watching the Dodgers lose is almost as gratifying as seeing the Padres win. Alas, twas not meant to be. If there is some twisted silver lining here, the bigger Goliath grows, the sweeter the victory when David finally conquers. IF David ever conquers…

Why did he slide though???