Every year the team is a new animal. Like the blind men and the elephant, we examine the different parts and make guesses about what the animal must be. As the season goes by our vision slowly returns and we can see how the disparate parts come together as a whole. We’re now nearly halfway through the season and starting to understanding this team’s final form. The team has performed in the highest tier of the league when it comes to run prevention. That performance appears sustainable. For such a wild roller coaster of a season there has, ironically, only been one consistent source of failure: the offense, and specifically the inability to hit with runners in scoring position (RISP). The irony is deeper when one realizes that the better part of a half billion dollars was spent this offseason signing players meant to ensure the offense would be a source of strength. Achilles’ heel, Superman’s kryptonite, and runners on first and second with less than two outs. Each of these are a fatal weaknesses to an otherwise monolithic strength.

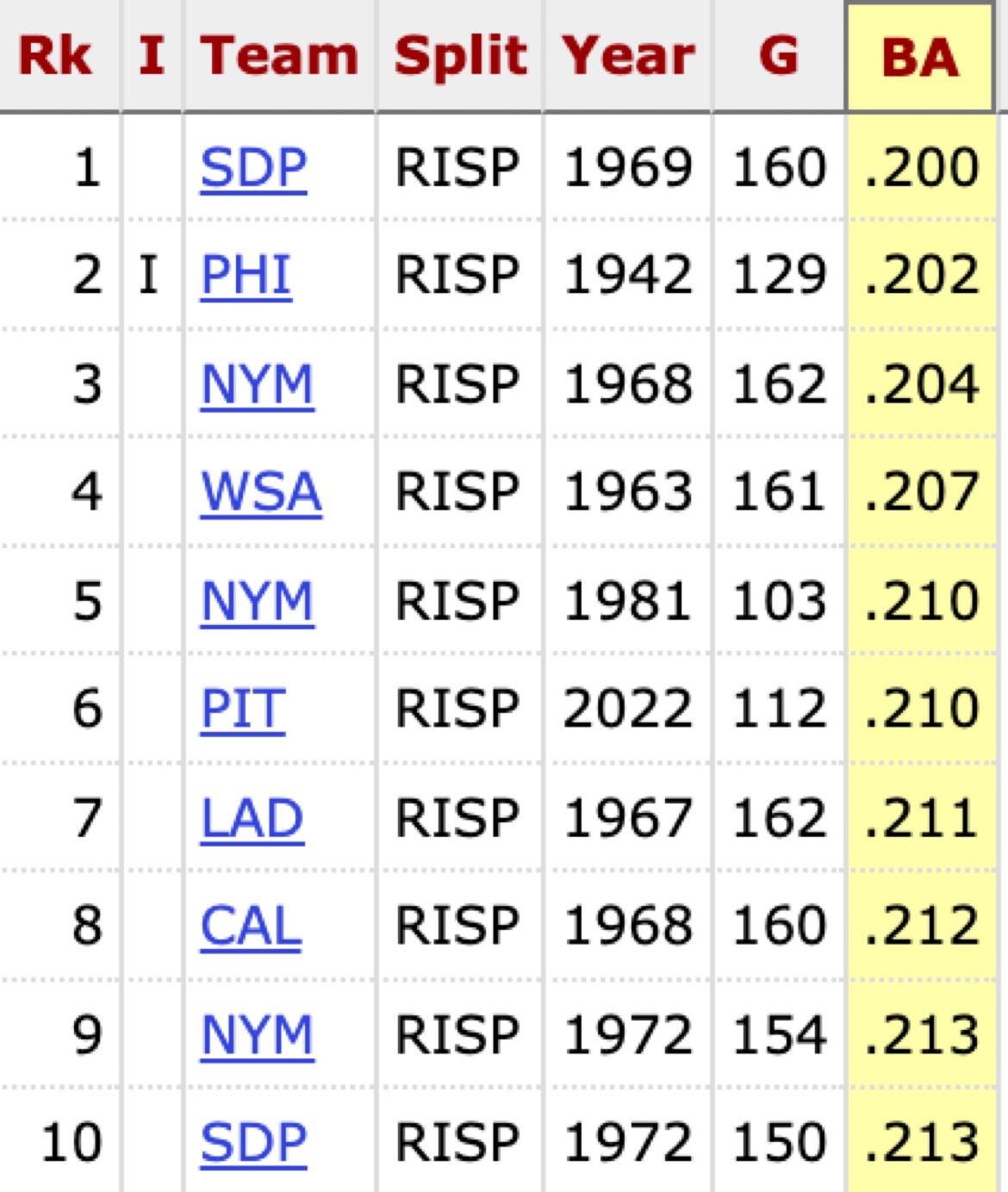

As we said before, there have been about 3000 total individual team seasons played in MLB’s 148 year history. Going into Thursday the Padres were the worst team of all time in batting average with RISP. But you would never know this was the same team watching the last two games. Thursday the Padres were 5 for 10 with RISP during a 10-0 dismantling of the Giants. Friday the Padres followed up against Washington by going 6 of 14 with RISP on the way to a 13-3 blowout. Games like the last two make you wonder what could have been, if only a literal slump for the ages hadn’t befallen the offense.

It’s actually possible to get an approximation of what might have been, and as we approach the trade deadline it’s increasingly urgent to do so. Bill James made famous the Pythagorean wins expectation formula which estimates what a team’s record should be based on the runs allowed and the runs scored. The Padres expected record this season so far is 43-33, exactly the same as the San Francisco Giants who just won 3 of 4 games during which they never appeared to be the better team. There’s a parallel universe where this exact Padres team is 2.5 games out of first and firmly in the playoff hunt. But that’s not this universe, and so our focus must be on the games that haven’t been played yet.

A reasonable estimate to make the playoffs is a win total of 87, which would have been good enough to make the playoffs each of the last 3 full seasons given the expanded playoff format. The Padres are currently 37-39. They need 50 wins to get to 87 by season’s end. There are 86 games left to play. They have to go 50-36 over the remainder of the season to reach 87 wins. There’re a lot of ways to look at the probability of the Padres achieving that record. To go 50-36 will require a .581 winning percentage the rest of the season. That’s just between what the Giants (.566) and Diamondbacks (.597) have achieved so far. So either the Padres will have to play better than they have so far, or they will have to get lucky (as it appears the Diamondbacks have) to make the 87 win threshold. Is there any reason to think the Padres will play better over the final 86 games than they have so far?

Paradoxically it is from the team’s greatest weakness that the strongest reason for optimism can be found. The BA with RISP has been so historically bad, it is very likely to undergo positive regression. We just need to emphasize again, before Thursday the Padres BA with RISP was the worst in 3000 years worth of individual team seasons. There’s very little chance of that trend continuing because this offense isn’t anywhere near the worst offense of all time. In fact, if the team’s performance with RISP had even been league average it is likely that they would have scored at least 30 more runs this year: The 2023 Padres have had 640 ABs with RISP and have 131 hits. If instead they’d batted the league average .255 in those situations they would have 163 hits, 32 more than they actually do. We conservatively estimate that 32 more hits with RISP could have produced another 30 runs. If we project the team’s performance to date with league average performance with RISP and resulting increase in runs scored, the run differential would be an impressive +68 (based on the assumed 362 runs scored vs 294 runs allowed), good for second in the NL. The resulting Pythagorean expected winning percentage would be .603. Why does any of this matter? If the Padres can finish the season with a .603 winning percentage from here on out, they will finish with 89 wins, very likely with a playoff birth, and as we know once a team makes the post-season anything can happen.

The past two games have seen massively better performance from the Padres hitters with RISP, a combined 11 for 24 and good enough, for now, to move the Padres up to only the 4th worst performing team of all time:

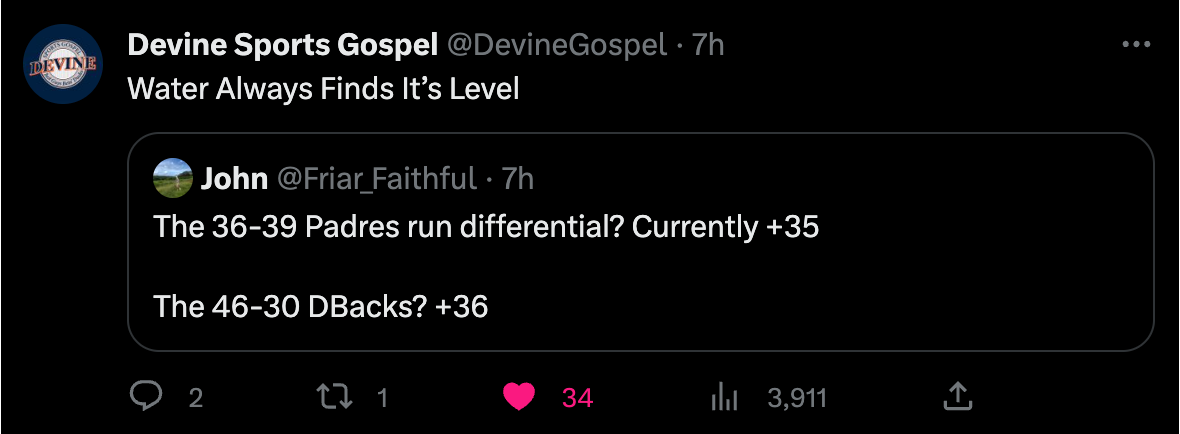

You really, really want to think Friday’s demolition of the Nationals is the beginning of something, a trend back to normalcy. But that’s the thing, you just can’t know because knowledge of trends does not accrue in single games. We are forced to have to wait to see. But there’s a saying “Water always finds its level.” The reason to feel it’s likely that a positive trend is coming is if you believe this Padres lineup is significantly better than the worst team in baseball history. It’s not unreasonable to think that is true. If you accept that is true, then it follows that more than likely the Padres woes with RISP to this point have been the result of some degree of unsustainable bad luck, which will start to normalize.

The division leading Diamondbacks winning percentage is .597, but on Thursday the Padres run differential on the season surpassed the DBacks. After the tweet above was sent the Padres stretched their run differential to 38 while the DBacks regressed to 34. Despite all the myriad concerns over the Padres performance to date it’s the hitting with RISP that underpins their struggles.

There’s a very strange symmetry to the unexpected success the Diamondbacks have had, and the unexpected struggles of the Padres. Through 76 games, the Diamondbacks are the team the Padres were supposed to be. The task before the Padres is to finish the final 86 games with the same success Diamondbacks have had so far. Their clearest path to do so is to become a league average team hitting with RISP. The symmetry runs deeper when we look at the team ranked 15/30 at nearly exactly the league average hitting with RISP:

Again, put very simply, the season rests on the Padres ability to finish the year with the same success that the Diamondbacks have achieved so far. That’s it. If you think that’s possible (it is) then there is reason for hope. There is reason to keep the faith.

Inevitably the talk in the next 2 weeks is going to turn to whether AJ Preller should be mortgaging more of the team’s future value (prospects) to enhance its present value (#BringTheGoldschmidt). Someone bid $6200 in the Padres media auction Friday night to be an “Executive for a day.” They’ll spend the day going to front office meetings and touring the grounds. If they agree to a date soon they might even get to witness the fury behind the scenes as AJ and Co. wrestle with whether to spend more future capital to increase the odds of surviving that 86 game gauntlet into the post-season.

A final thought: In most seasons the best team in the league does not win the World Series. The bizarre profile of the average World Series winner has been 7th in offense, 8th in pitching, and 8th in defense over the last 25 seasons. A team with that profile would not jump out as a World Series contender but the evidence suggests they would be one. When you deconstruct it, that shouldn’t be terribly surprising. Great performances over 162 games don’t always translate to short series postseason play where variance takes on a larger role, and the margins between teams in the top third of the league are fairly slim. That is both a lesson about the risk of overconfidence, but also about the risk of under-confidence. It’s natural to feel that unless your team is clearly one of the best in MLB that it’s just not your year, and that the focus should be on the future. But the evidence shows that is far too pessimistic an outlook, and punting when the team is good but not great can carry a much higher opportunity cost than we intuitively think. History suggests any team good enough to make the playoffs, is good enough to win the World Series. If we think we can run that 86 game gauntlet and break into the postseason, we should try.

As hard as it is, keep the faith. We’re doing our best.

Excellent piece.