Margin Call Part 3

Pitching to the Park

The Padres took two of three games against the Rockies this weekend. Creativity hasn’t been one of the team’s strong suits in 2025. But this series showcased a different side. There was lineup dynamism, including an interesting offense-maximizing lineup on Sunday when Jake Cronenworth was moved to shortstop and Luis Arraez to second base to allow all three of Ramon Laureano, Gavin Sheets, and Ryan O’Hearn to take the field. It also saw two Padres starters make major approach changes, exercising agency over one of the few things they can control in the chaotic confines of Coors Field: Playing to the park.

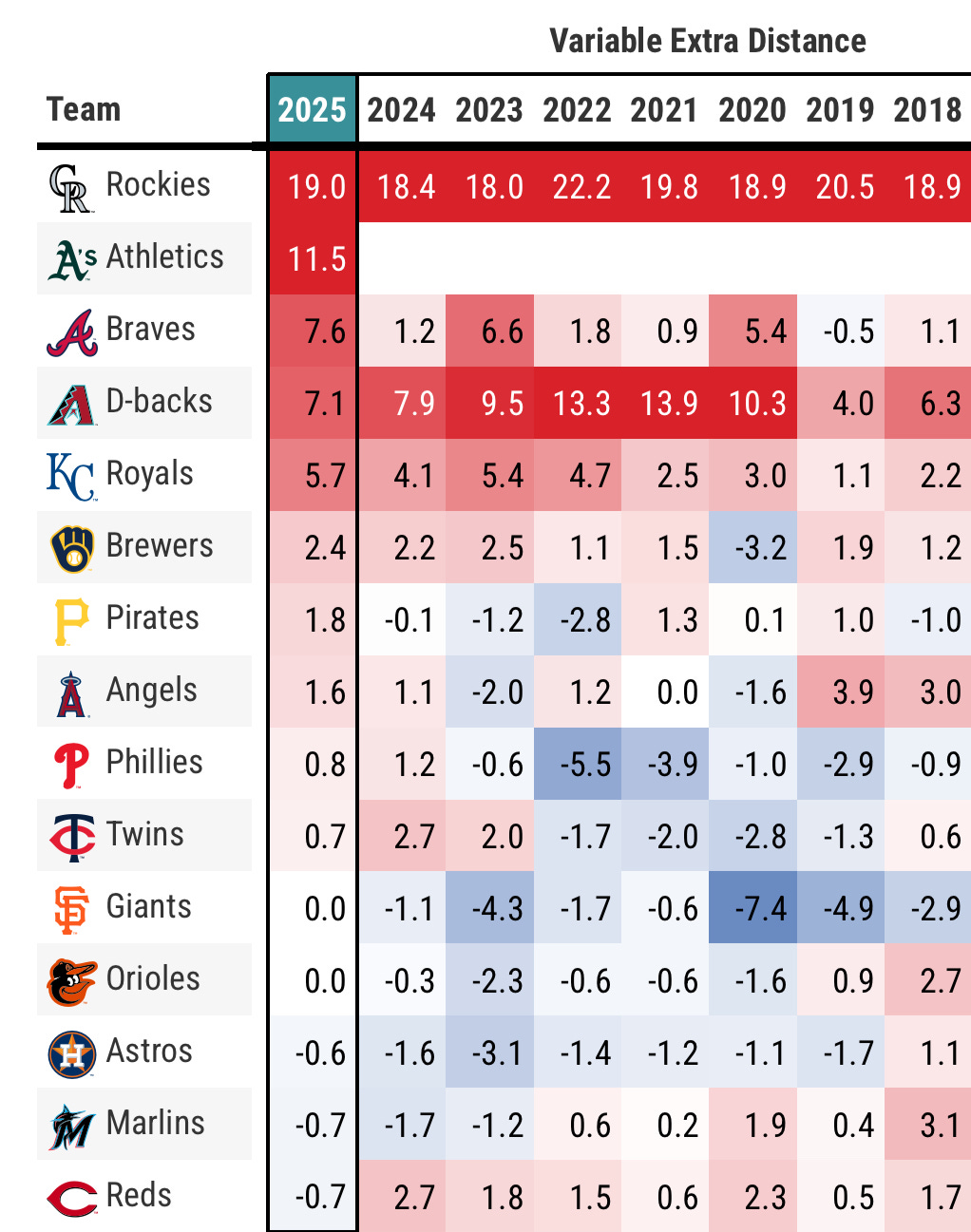

Coors Field is the most extreme ballpark in baseball. It has some of the deepest dimensions, but is one of the most home run heavy parks in baseball year after year due to the extreme altitude and low air density permitting fly balls to travel much further than any park in baseball:

The lesser known aspect of Coors is the dramatic effect it has on pitch speeds and shapes.

Books like The Physics of Baseball, and later studies by the University of Illinois articulated the theoretical effects of pitching at altitude, but it wasn’t until the wide availability of Statcast that the effects could be quantified in major league games. And with this data the outline of an optimal arsenal for finding success in Coors has started to take shape. In a blog post in February a data analytics firm summarized the relevant considerations when designing a pitch arsenal for success in Coors:

The thinner air reduces the Magnus effect, meaning movement induced by spin will be lessened.

Reduced Air Density (~82% of sea level) creates less drag on the way to the plate, leading to more retained velocity as a pitch crosses the plate.

At sea level a pitch will typically lose ~10% of its release velocity by the time it crosses the plate, while the thinner air in Coors leads to ~8% loss in velocity, or about 1-2 miles per hour.

Gyro spin (spin aligned around the flight path of the ball) is not heavily affected by altitude

You can apply these observations to specific pitch types:

Four-Seam Fastball

Will lose lift (decrease in induced vertical break) due to reduced Magnus force. A pure four-seam fastball will drop ~4 inches more than at sea level.

Elite high-spin fastballs (Pivetta, Cease, Jeremiah Estrada) become less effective, especially those aimed at the top of the zone.

Low-spin, high-velocity fastballs can actually gain effectiveness because they retain more velocity due to less drag and less magnus effect on the way to the plate.

Sinkers

Loses arm-side run and ride, causing the pitch to flatten out.

Low-spin, high-velocity may play up.

Cutters

Less reliant on Magnus force for movement, spin axis/tilt induced movement less affected by altitude.

Benefit from retained velocity.

Curveballs

Break is reduced significantly due to the decrease Magnus force.

Pitches will “hang” more, making them easier to hit.

Changeups

Changeups that rely on horizontal movement (Wandy Peralta) will suffer more than those that rely on deception (Robert Suarez)

Sliders/Sweepers

Less affected than curveballs because more of their movement comes from gyro-spin/tilt

Thrown faster than curveballs and may benefit more from retained velocity

Coors quite literally prevents pitchers from executing the same game plan that makes them successful in other venues. And that’s why it was anxiety provoking to see Nick Pivetta and Dylan Cease were slated to start the first and third games of the series (to say nothing of Randy Vasquez being asked to spot start). But each of them achieved success, indeed the most success any Padres starters have recently. Randy Vasquez’s success continues to amaze, and defy explanation. But in Pivetta and Cease’s case there’s likely some explanatory power in choices they made.

Pitch Selection

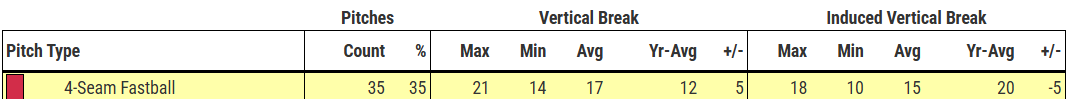

If you had to choose the pitcher most likely to have spectacularly bad results at Coors, you might choose Nick Pivetta, who relies on the extreme induced vertical break (iVB) on his four-seamer, and pairs it with a steep 12-6 curve. Pivetta’s four-seamer averages a superb 20 inches of induced vertical break on the season, generating a ton of whiffs as the fastball ride induces swings underneath the ball’s trajectory. But in Coors he is only able to achieve 15 inches of iVB, meaning fastballs aimed toward the top of the zone are apt to drop into the heart of the zone, and the ball’s flight path is much truer to the trajectory the hitter’s brain senses out of the hand:

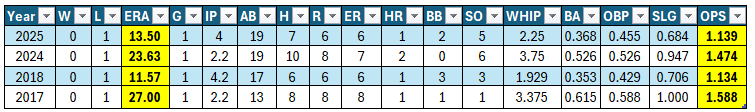

And this has been a major problem for Pivetta in the past. Heading into Friday’s game, Pivetta had struggled more in Coors Field than any other ballpark:

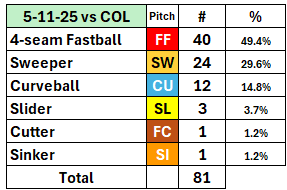

And it’s interesting to look at the pitch mix from his first start in Coors May 11th, an outing in which he gave up six earned runs in only four innings:

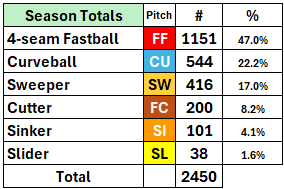

Of the 42 fastballs he threw, 40 were the especially ineffective four-seam fastball. He only threw one sinker and one cutter to mix things up. He threw an even split of fastballs and breaking balls. This was a very similar pitch mix to his season averages:

In May he was trying to execute his usual pitch mix, and was shelled. There was not much evidence of a Coors specific game plan. As we wrote at the time, the very first pitch of that game was a four-seamer that ended up several inches below the top of the zone:

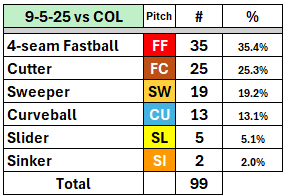

Friday’s start was his first trip back to Coors since that disastrous outing, and there was a stark difference in his pitch mix Friday night:

He threw 25 cutters, and ~63% fastballs overall. It was the most cutters he’s thrown in a game since 2022. And the choice of cutter over sinker likely has to do with the cutters’ ability to retain shape slightly better due to getting less of its movement from pure Magnus force.

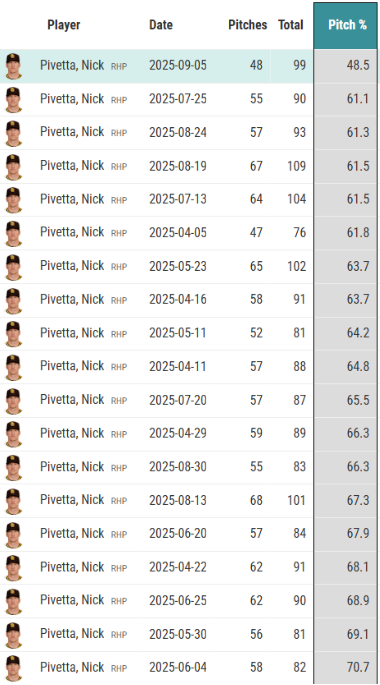

When he threw breaking pitches he threw sweepers/sliders twice as often as the curveball. He combined for only 48 four-seam fastballs and curveballs, a usage of only 48.5%, the first time he’s had a combined usage of less than 61% this season:

It’s not a coincidence. This is a game plan. And it was adjusted for Coors.

You can see how the pitch mix evolved successive times through the order.

The first time through was almost exclusively a mix of fastballs, with heavy use of the cutter, and the only two sinkers he threw all night. The second time through he started to mix in more breaking balls, but threw 14 sweepers/sliders (the more effective breaking pitches in Coors) to only four curveballs. He only dared to throw multiple curveballs to Warming Bernabel who has been exceptionally good against sliders in his short career. The third time through he constantly mixed all his pitches, with only two hitters seeing the same pitch type back-to-back, including three straight curveballs to Bernabel who rolled over the third one for a groundball double play to end the outing.

Pivetta turned in—far and away—his best outing ever in Coors, completing six innings with only 2 earned runs. And it’s not a stretch to think that was in part because of a different pitch mix than he has thrown at any other point this season. He was controlling the one thing he could, pitching to the park he was in rather than relying on what has made him successful throughout the season in other venues. In 2024 the cutter was his worst pitch, one of the worst in baseball by run value. It’s been more effective in 2025, but his four-seamer has been one of the single best pitches in baseball with a +16 run value. Trading four-seamers for cutters is a foolish proposition, except when the environment is certain to stilt the effectiveness of the four-seamer to a much higher degree than the cutter, and the benefit of increasing the difficulty of the guessing game for the hitter might be the only path to success:

This was one of only two sinkers Pivetta threw all night, and the horizontal break got in on Jordan Beck’s hands, sawing him off despite having been sitting first pitch fastball.

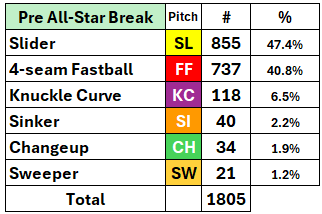

It was even more interesting to see the changes to Dylan Cease’s arsenal in game 3. Coors also profiles very poorly for Cease’s usual success formula of a high ride four-seam fastball and slider combination. We wrote about Cease’s struggles in the first half of the season coming in part from comically high reliance on the four-seamer/slider combination which had reached 88.2% usage going into the all-star break:

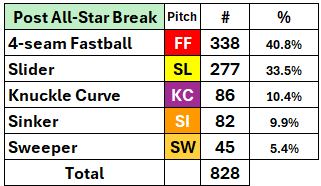

Cease came out of the break with a major shift in his arsenal, initially reincorporating the knuckle curve, and subsequently increasing his use of the sinker:

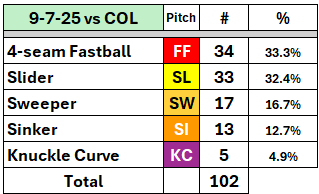

At first, watching Cease pitch on Sunday looked like a reversion to his pre all-star break 2-pitch mix, with almost exclusively fastballs and sliders. But on deeper inspection it was actually a much more interesting pitch mix:

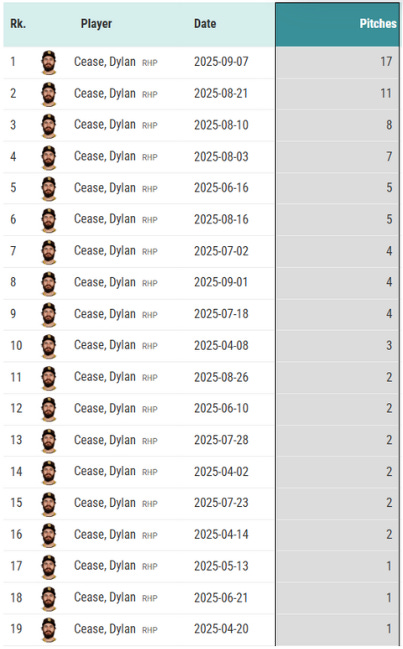

The key here is the use of the sweeper. He set a career high throwing the sweeper 17 times, and reaching double digit usage for the first time since 2021:

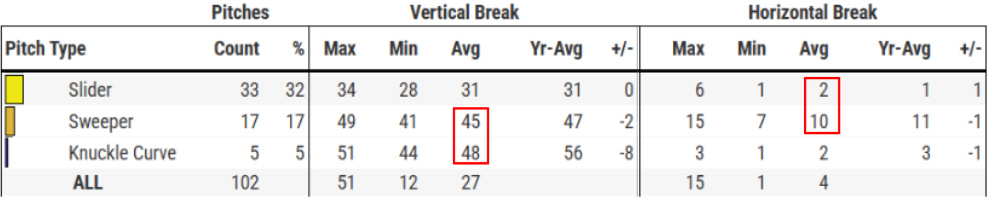

And there’s a good physiologic reason for this. Recalling the Coors Field effects above, within Cease’s arsenal the knuckle curve is the pitch most likely to be ineffective at altitude. While the four-seam fastball loses ride, it benefits from retained velocity which helps a pitcher with elite velo like Cease maintain effectiveness. The sweeper shows better ability to maintain shape because of the larger contribution from gyro/tilt which is unaffected by altitude. The curve simply loses the break that makes it effective without any favorable tradeoffs. And when you look at Cease’s three breaking ball shapes you see a very interesting juxtaposition in how they played at Coors Sunday:

The slider essentially retains its shape. But the altitude destroys the vertical break of the knuckle curve and brings its total vertical break much closer to the sweeper. At sea level the knuckle curve gets plenty of separation (56 inches drop) from the vertical plane of the slider and the sweeper (31 and 47 inches drop at sea level, respectively). At altitude that vertical separation is cut in half as the knuckle curve achieves 8 inches less drop compared to sea level due to the lower Magnus effect. The sweeper suffers a far less-harsh penalty due to how its break is created (gyro spin/tilt) and the end result is the sweeper gets nearly as much vertical separation from the slider as the knuckle curve, but has the advantage of separation on the horizontal plane. The sweeper is thrown harder as well, which can increase its effectiveness compared to the knuckle curve. The sweeper is simply the better choice to give the hitter a different look on a breaking ball at altitude. And effectively Cease replaced the knuckle curve usage with the sweeper.

Cease also gave hitters many more looks at the sinker. While both the four-seamer and sinker lost a lot of the movement characteristics that make them effective pitches, the slight difference in horizontal break made it a bit more difficult for hitters to square the pitches up. Cease worked in the sinker early and often throughout his outing:

Though it wasn’t as obvious as other outings, on Sunday Cease ultimately threw four pitches with at least 10% usage. Creating a more difficult guessing game for the hitter is one of the keys to maintaining effectiveness multiple times through the order. This, too, was clearly game planned. And Cease managed to pitch five innings giving up only 1 earned run.

Cease and Pivetta both made drastic changes to pitch mixes, both upping the usage of of one of their least used pitches, and specifically a pitch that was more likely to retain shape at altitude (Pivetta’s cutter, Cease’s sweeper). This is very smart game planning, and in Pivetta’s case, something that wasn’t seen in the team’s first trip to Coors Field.

Accounting for the atmospherics of the ballpark when game planning is one of the things the team can control. It’s true that there’s no perfect way to pitch in Coors, it’s picking from nothing but bad options. But it looks like the Padres put real effort into getting to the choice that is least-wrong.

Matching Pitcher To Park

There’s another side to consider. While Pivetta and Cease were pitching in their scheduled spots in the rotation, Randy Vasquez was a spot starter. The team decided to have him throw from among the available arms. Strandy has certainly earned a chance to make another start. But the team may need more than one spot starter down the stretch. If they do it will likely be JP Sears. The thought is enough to cause some (us) to break into cold sweats. But it might be necessary. And if it is, one locus of control the team might have is how it sequences its spot starts. Who takes a game on the road vs at home. That sounds trivial, but it might not be.

Vasquez does not have extreme home/road splits:

Neither does JP Sears:

But Sears does have a certain type of split. He seems to pitch much better in ballparks that suppress fly ball distance and home runs. It’s probably true that all pitchers are better in these parks. But Sears is an an extreme fly ball pitcher, meaning the performance volatility for Sears in a pitchers park vs a home run heavy park will be much higher than that of an average pitcher. As extreme as Coors Field is for hitters, Petco is nearly as extreme for certain pitchers. Those like Nick Pivetta. Pitchers that struggle with giving up home runs due to high fly ball rates. Sears is one of the most extreme in this regard. And in parks similar to Petco, Sears has pitched surprisingly well in his career.

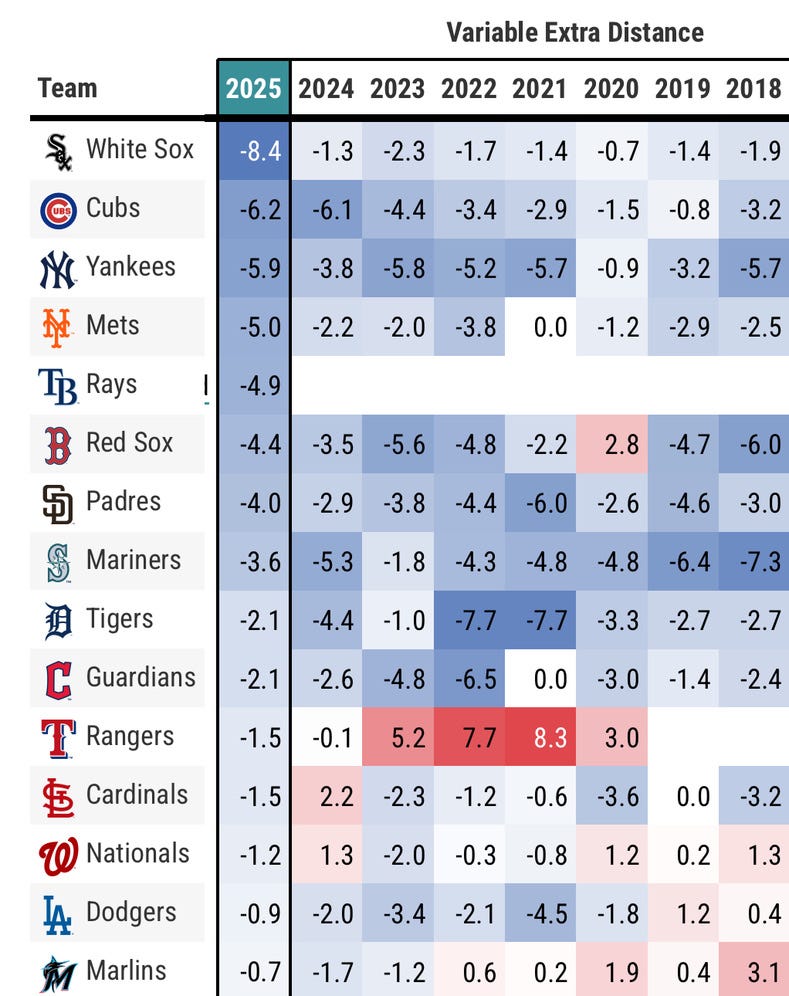

Here is the bottom of the league’s ballparks for added fly ball distance:

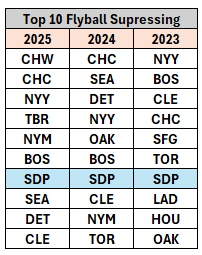

Petco is consistently one of the most fly ball suppressing parks in the league, one of only five ballparks to be ranked in the top 10 in fly ball suppression each of the last three years:

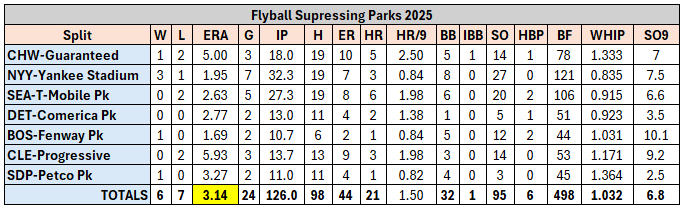

Here is how Sears has pitched in the top flyball suppressing parks of 2025 across his career:

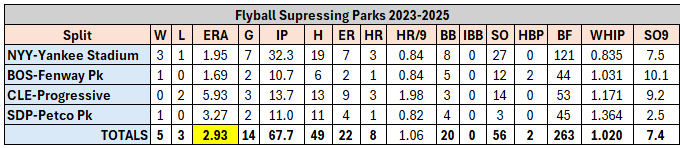

126 innings is still a small sample, only two-thirds of a season or so. And the sample sizes don’t get any larger when you narrow the criteria, but here’s how he’s pitched in the ballparks that have been in the top 10 of flyball suppression each of the last three years:

There’s more to home run prevention than just flyball suppression, park dimensions matter a great deal. And even after Nestor Cortes’ extended batting practice sessions (he’s given up 5.3% of the total home runs in Petco in just two starts) Petco Park is still a top 10 home run suppressing park in 2025, the second time in three years. And, there’s more to offense than just hitting home runs. Petco Park is also ranked 6th in overall offense suppression. Here’s how Sears has pitched in the parks with the lowest overall park factors the past three years:

It turns out Petco is the only park in baseball to be bottom 10 in flyball distance each of the last three years, bottom 10 in home run park factor two of the last three years, and bottom 10 in overall park factor over the past three years. The Padres are going to play games at three of these parks across the final 19 games (Petco, against the Mets in New York where Sears has never pitched, and against the White Sox in Chicago). If even one of those games needs to be covered by JP Sears, there’s reason to think he may be significantly more effective in Petco than on the road. This is not a projection that Sears will be good in Petco. It’s more a projection that he has a chance to not be as bad in Petco. If the team has the option to sequence a spot start at Petco or on the road, the nudge should be to Petco. Because a few feet of flyball distance suppression, a wall just a few feet further, or both, can matter a lot.

Heck, even a few inches can matter:

We’ll be back for part 4.

It’s odd how what amounts to a small change in pitch mix can make a pitcher so much more effective. Adding just that little bit of uncertainty - holding all other variables the same- can have such an impact potentially. Hitting is hard. Adding that uncertainty has to help on the margin.

Great article again Archi! One minor correction, Brewers are coming to Petco two weeks from now.