The Padres followed up one of the most dramatic wins of the season Tuesday with an almost alarmingly routine win against the Dodgers Wednesday, in the process ending Clayton Kershaw’s MLB record of 423 consecutive starts recording a strikeout. The Padres scored four runs in the second and never looked back, largely shutting down the Dodgers offense and adding on runs in the fourth and seventh innings en route to an 8-1 victory. Yet as convincing as the short series sweep against the Dodgers was, there was the ever present fear that the other shoe was about to drop as the Rockies came to town for a three game weekend series amidst an increasingly competitive NL playoff race.

The Padres struggles against the Rockies are well chronicled, if not well understood. The Rockies are a very bad team, they have the second worst record in baseball. And they’re bad in a particular way. Their offense is not the problem, they score more runs per game than multiple playoff hopefuls including the Cardinals, the Pirates, and surprisingly the Braves. It’s the other side of the ball where they fail: they are truly awful at run prevention. They have given up 657 runs, by far the worst in baseball, a full 58 runs worse than the historically bad Chicago White Sox. Their struggles in run prevention come largely from abysmal pitching. They have the worst ERA in baseball at 5.50 as a team. However, the top of the rotation features Austin Gomber, Cal Quantrill, and Ryan Feltner. The trio are not good, but all have ERAs that hover around league average. They have made 66 of the Rockies 113 starts. But the other 47 starts have been made by a morass of ineffective arms with a combined 6.07 ERA. It’s this bottom of the rotation that has done an immense amount of damage to the Rockies team ERA and W-L record. And it’s important to note this because, while it’s true the Rockies are a very bad team, teams are not monolithic, and when Gomber, Quantrill, or Feltner are on the mound the team is only slightly below average offensively as well as on the run prevention side. And the Padres always get the Rockies best effort.

With that having been said, -nothing- can satisfactorily explain why the Padres came into Friday’s home series against the Rockies with a 2-5 record against them on the season. That record is worse than you’d expect even accounting for the Rockies having better versions of themselves. To be sure, there is a lot of luck flying around. The Rockies 2-out batting average with runners in scoring position during the home sweep in May was the stuff of nightmares… It’s probable that the explanation for the Padres struggles against the Rockies is the combination of the Rockies being a better team when they have a competent pitcher on the mound than their record would suggest, and that some very good luck has fallen their way… You can tie yourself in knots trying to find a more satisfactory explanation. But none ever materializes. And so that’s not how we’re going to proceed from here. Suffice it to say that some things don’t have a satisfactory explanation. The Rockies vex the Padres and no clear reason can be articulated. But what the Padres showed in the weekend series can be articulated, and gives us a glimpse of the team’s final form. Game 2 deserves the most attention but we’ll recap the whole series.

Game 1

Friday night saw Rockies lefty Austin Gomber throw yet another gem against the Padres, pitching seven innings and giving up only two runs. On the season he’s pitched 18 innings against the Padres and given up only three runs. Still, the Padres had a 2-1 lead entering the sixth inning. Jeremiah Estrada was brought in to protect the lead but lost full-count battles to the first two hitters, issuing walks to both, before Brendan Rogers hit an infield single to load the bases. Estrada would strike out Michael Toglia. Kris Bryant would follow with one out and the bases loaded. Bryant would add on to the seemingly endless parade of improbable Rockies base hits with runners in scoring position when he blooped a fly ball single into right center field with an exit velocity of 71.7 MPH. Estrada would strike out Elias Diaz next, but Jake Cave followed with another soft contact single this time 85 MPH exit velocity to center field plating Rogers. Just like that the Rockies led 4-2. They would add on in the seventh when Alek Jacob gave up back to back singles with exit velocities of 81.1 MPH and 69.1 MPH followed by a sac fly. The Rockies would lead 5-2 in the eighth when Jurickson Profar seemed poised to start another come from behind rally:

Courtesy: @MLB

That ball was hit 105 MPH off the bat with a 31 degree launch angle, it traveled 400 feet to right center and would have been a home run in 25/30 MLB ballparks. This is how it goes against the Rockies. They would win the first game 5-2.

Game 2

Game 2 is the most noteworthy game of the series and numerous aspects deserve attention. Game 2 saw the debut of Padres trade deadline acquisition Martin Perez. Perez was sharp going six innings giving up only one run on a solo home run to Hunter Goodman. But in another vexing turn Rockies 26 year old rookie Tanner Gordon, who entered the game with an 8.80 ERA through his first three major league starts, pitched a perfect game through the first four innings. Despite the strong performance from Martin Perez, the Padres trailed 1-0 in the fifth. Again, this isn’t something that can be easily explained.

The bottom of the fifth inning would turn out to be pivotal, and unfolded in an unusual manner. Manny Machado led off and worked a full-count walk for the Padres’ first base runner of the game. Xander Bogaerts followed and got a bit of good fortune on an infield single. This brought Jackson Merrill to the plate with runners on first and second and no outs. Still trailing by one run Merrill elected, apparently on his own, to sacrifice bunt:

Courtesy: @TalkingFriars

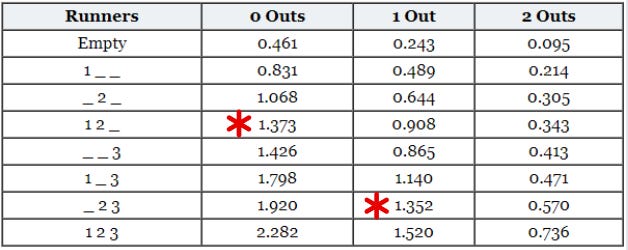

We wrote before about why it may not be as bad a decision for Bryce Johnson to bunt as we’ve all been conditioned to think (bunt=bad). The key to that analysis is that Johnson appears to be a below average major league hitter. That same calculus can’t be applied to Merrill who is an above average hitter. This was a play that if repeated infinite times probably costs the Padres runs in the long term. Here is the RE24 matrix which describes the likely change in run expectancy based on the bunt:

The successful sacrifice bunt moved the Padres from a base/out state that historically is expected to produce 1.373 runs to a base/out state expected to produce 1.352 runs. A net cost of 0.021 runs. If this occurred once per game across a 162 game season this would cost the team an estimated 3.4 runs. That’s not a negligible sum. But interpreting this as pure downside misses the tradeoff that was probably the impetus for Merrill’s decision. Successfully executing the sacrifice bunt did decrease the total run expectancy for the inning, but increased the chances of at least one run scoring from 63.64% to 67.96%. This doesn’t mean it was the right decision. Home teams trailing by one run in the bottom of the fifth with runners on first and second and no outs have come back to win the game 57.56% of the time. In the base/out state of runners on second and third and one out the home team has won only 55.6% of the time. That’s a pretty modest return for sacrificing an at bat from one of your best hitters. There’s a good argument to be made that bunting was not the best decision to maximize win probability across many iterations of the game. But you can see it’s pretty close. And importantly, the RE24 statistical evidence for run expectancy has all context stripped away - it presumes average conditions implicitly. To reiterate from our Bryce Johnson analysis:

The RE24 analysis came from identifying the average outcomes of an enormous corpus of data. It was very sound analysis and very insightful. It revolutionized how the game was played. But by virtue of being a model based on average outcomes, it implicitly assumes the quality of the players on the field are average. It assumes the hitter at the plate is average. And the hitter on deck is average. And the pitcher is average. And so on. This is an unavoidable implicit assumption when data is modeled in this way.

Merrill probably correctly understood that if the Padres could tie the game, the game script likely heavily favored them to win because the Padres bullpen (bolstered massively at the trade deadline) is much stronger than the Rockies. Like minds can and probably should disagree on whether it was the correct strategic decision. These are inferences made under irreconcilable uncertainty. And there are pieces of information that we simply cannot access. For example we think it was a bit of a fluke that Tanner Gordon pitched a perfect game through the first four innings. But we didn’t face him. Jackson Merrill did. And he elected to bunt in a situation where we would have had him swing away. He knows more about the situation than anyone. After the game manager Mike Shildt made it clear that Merrill made the decision to bunt on his own. Shildt also called it a good baseball play. He put his faith in Merrill’s decision making, so maybe we should as well. Still, we’re not thrilled that Jackson Merrill bunted when he did, but it’s notable that he executed it perfectly, and we definitely feel it’s a much-too-close decision to simply fall back on the bunting=bad trope.

The successful sac bunt did set up the opportunity to score with a productive out, and David Peralta did exactly that, grounding out to second base and plating the tying run.

The score would remain 1-1 into the bottom of the seventh when Jake Cronenworth led off with a single and Manny Machado followed with a double down the right field line putting runners on second and third for Xander Bogaerts:

Courtesy: @Padres

The Padres took a 2-1 lead after back to back hits from Machado and Bogaerts, something that the Padres have seen precious little of this season. Jackson Merrill would follow, and after quickly falling behind 0-2 he got a pitch middle-middle and elevated a fly ball to left field deep enough to score Machado from third. 3-1 Padres.

What was interesting about this Merrill at bat was his changes in bat speed and swing length. With runners on first and third he took a big cut at the 0-0 offering but was fooled on a change up low and away. His swing speed was 69.7 MPH and swing length was a very long 9.2 ft. On the season his average swing speed has been 71.7 MPH and the decrease on this swing likely had to do with being out in front of the pitch. With the count 0-1 he got another changeup and put a better swing on it but was still slightly out in front and fouled it off. This time his swing speed was a healthy 70.9 MPH and his swing length a still long 9.1 ft. This is when things changed. With the count 0-2 Merrill got the middle-middle fastball, slightly elevated; the perfect pitch to drive. And indeed he got the barrel of the bat on it, driving it to the warning track in left for a sac fly. But what’s so interesting is his swing speed: it was the slowest of the at bat at 69.2 MPH. The swing length was a dramatically lower 7.3 ft as well. He literally shortened up and took a contact swing to drive in a crucial run late in the game, sacrificing some chance at power for a better chance at contact in a situation where contact is rewarded much more than it typically is. Here’s the entire sequence:

We’re in an era where technology is starting to let us see that certain players can mode switch between approaches. Certain players can clutch up.

The sac fly would turn out to plate the winning run as Tanner Scott allowed a solo shot to pinch hitter Jacob Stallings in the eighth to cut the lead to 3-2. But Robert Suarez was able to close out the ninth to secure the Padres one run victory.

Perhaps the most visceral observation from this game has to do with the decisions made by Merrill. His decisions at the plate didn’t feel like regular season baseball decisions. These felt like the type of decisions that might be made in a short series. This felt like playoff baseball decision making - reevaluating tradeoffs that make sense when you’re playing a large sample size game where more runs over more iterations is the more favorable tradeoff. It’s worth considering which situations imply that calculus should change; when foregoing some upside in favor of a higher likelihood of scoring at least enough runs to survive becomes the more favorable tradeoff. Very fun stuff to consider in an early August game against a last place team. Again nothing comes easy against the team from Colorado. The Rockies series’ have been excruciating at times, but they’ve been fascinating as well.

A crucial sequence of the game involved Xander Bogaerts driving in a run with a base hit. He’s been doing this a lot. Since his return from the IL July 12th Xander Bogaerts has a 1.034 OPS, and it hasn’t been empty calories. His average exit velocity has been 89.6 MPH, well above his season average of 87.1. More encouraging: his hard hit percentage during this span has been 43.1%. This appears to be real production underpinned by real physical performance. Of course Bogaerts is not going to maintain a 1.034 OPS, but his underlying performance suggests his production may settle out nearer to his career norms than his disconcerting early season performance. The news is actually even better for Machado. In June we wrote about Machado’s well documented struggles to launch the ball despite consistently hitting it hard. At the time it appeared pain and post-surgical limitations in his throwing elbow were affecting his swing in subtle ways. He was still hitting the ball hard but was driving it into the ground with regularity. It looks like he’s made adjustments to get to more consistently healthy launch angles. In the same span since Bogaerts came off the IL Machado has been maintaining a scorching 58.9% hard hit percentage and a very healthy average launch angle of 15 degrees, much more in line with his production from years past. Over that stretch he’s slugging .642. He’s nine months out from offseason elbow surgery and it’s possible he’s returning to healthier form as a result. Machado and Bogaerts hitting like their usual selves changes the Padres outlook significantly.

Game 3

The Padres split the first two games of the series with back of the rotation starters Randy Vasquez and Martin Perez. Both games were extremely close. Game 3 saw Matt Waldron against Cal Quantrill. Matt Waldron made his 23rd start of the season, and another start that suggests his success this season represents real development rather than a hot streak. His knuckle ball was not only nearly unhittable, it was nearly uncatchable.

Courtesy: @PitchingNinja

Jackson Merrill showcased his situational hitting and decision making in game 2. In his first at bat in game 3 he found himself in the quintessential situation for a power hitter: the opportunity to drive in a runner from first base. The entire at bat is remarkable:

Courtesy: @PadresDataDaily

Merrill worked his way back from an 0-2 count to force seven more pitches in the at bat. He fouled off anything close to the zone, and laid off stuff well outside the zone. This puts incredible pressure on the pitcher. Quantrill put the ninth pitch in a good location, but by then Merrill had seen everything he had to offer and, demonstrating remarkable plate coverage, barreled up a pitch on the outside corner to the pull-side, getting to a healthy launch angle with a 101 MPH exit velocity to knock a double off the base of the right center field wall. That is elite in every facet. Merrill’s incredible versatility at the plate was on display in this series.

Quantrill would duel Waldron evenly through the fourth, but the Padres got to him in the fifth when Kyle Higashioka and Jurickson Profar homered. In the sixth Xander Bogaerts would be hit by a pitch and Jackson Merrill would follow taking a walk on four straight balls just off the plate outside. David Peralta followed, striking the killing blow with his first home run at Petco Park, a three run shot to give the Padres a 6-1 lead. And suddenly, for the second time in a week, the Padres found themselves with another alarmingly routine win. They would complete the series victory with a 10-2 final. A breath of fresh air. A palate cleanser.

The Hidden Curriculum

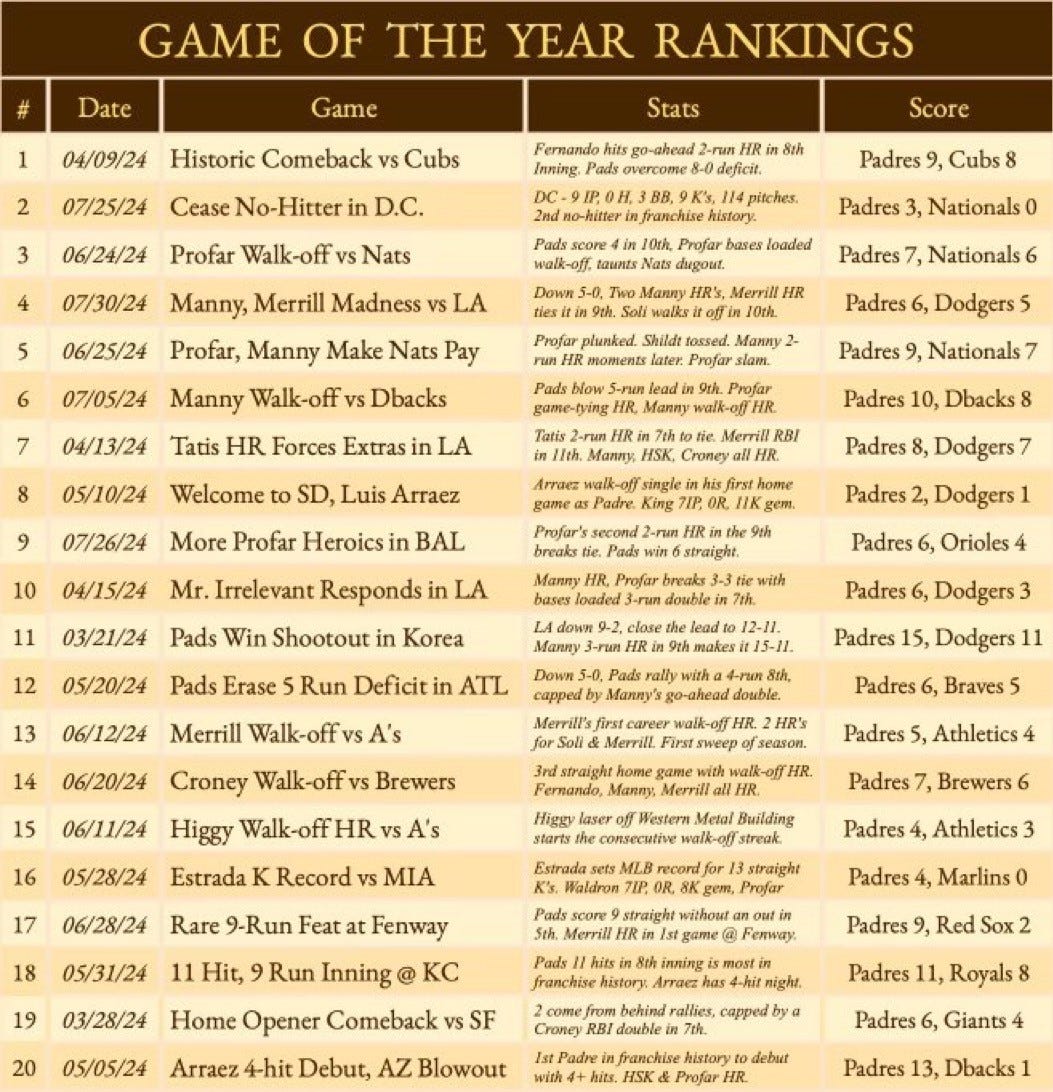

There’s a hidden curriculum to being a Padres fan, one that is taught not explicitly, but implicitly through observation of events that would seem to defy probability. We learn that nothing can be easy. There is always another shoe to drop. It’s always a false bottom… Year after year one gets the sense that the universe trends not strictly towards randomness, but rather that there is an entropic valence that bends towards Padres misery. These thoughts are ever front of mind, even in a season adorned with conspicuous examples that something might be different:

Courtesy: @RyanCohen24

It is indeed alarming when wins against vexing teams appear routine. But it’s what’s supposed to happen -at least some of the time- when preparation meets opportunity. The Padres took care of business this week. They remain in the most crucial stretch of games of the year. A stretch of nine straight games with no days off starts Tuesday. On paper this road trip doesn’t look nearly as daunting as that which they just completed. But if you’re a long time Padres fan you know better than to think that way. Nothing comes easy.

To add on, the analysis of Merrill was great.

Very fun and informative write up. Was braced for a series loss or sweep. It is not only that Gomber is part of the okay part of the Rockies rotation, but he has pitched very well and often against the Padres this season.

https://www.reddit.com/r/Padres/comments/1eiw1uw/austin_gomber/

He is also annoyingly bad against relevant competitors.

The HR by Peralta was a big relief. Johnson may be a better defender, but in FTJ's absence his wRC+ is 104 vs. Johnson's 44.

If history is any guide my exuberance is ready for punch in the gut, but still feeling it nonetheless. Hard not to fantasize about a healthy Musgrove, FTJ and, hopefully, Darvish.