News of the Luis Arraez trade did not exactly send Padres fans into fits of ecstasy. We had the same concerns as many who were alarmed by trading prospect capital for a player who’s game seems a bit like a relic of a bygone era. We knew his reputation: elite contact hitter. And we knew the two main critiques of his style of offense: singles hitters aren’t as valuable as power hitters, and players who don’t consistently hit the ball hard won’t find consistent success. That made us seriously question how much value the Padres got back. On the other hand, we also had a vague sense that the advanced analytics community was starting to think differently about Arraez. So, we decided to dive deep. What did the Padres just add?

Where It Started

The magic duo of Statcast and sabermetrics have confirmed something that people have known for about 150 years: it’s very important to hit the ball hard:

Source: Phanalytics

If you’ve ever wondered where the definition of “Hard-Hit” that you see on Baseball Savant comes from it’s this chart and other’s like it that consistently reproduce the finding that hitting the ball hard, i.e. >95 MPH, is the best way to generate consistent offense. But somewhere along the way, for some of us, that message transformed into: hitting the ball hard is the only way to generate consistent offense. It turns out there are emergent properties when a player’s contact tool becomes so good that he can consistently churn out high quality, if not hard-hit, balls in play that defy the typical rules of thumb about batting average on balls in play.

Rober Orr wrote what is probably the best distillation of the unique traits of Luis Arraez:

He consistently has the lowest whiff rates in the MLB;

While his exit velocities are rarely >95 MPH, he’s at the top of the league in average exit velocity on non-hard hit balls ranking 2nd, 1st, and 2nd the past three seasons typically around 85 MPH;

His exit velocities have had the lowest standard deviation in baseball for three years - meaning there’s a much narrower distribution of his exit velocities than most players;

His launch angle standard deviation is among the lowest in the league - meaning the balls he puts in play are within a narrower launch angle range;

He’s among the best in the MLB at hitting the ball on the sweet-spot, meaning a launch angle of 8 to 32 degrees, which are the most productive ranges for hitters.

In a nutshell: When he swings, he makes contact, the contact is usually a not-too-shabby line drive, and that line drive is usually hit at an angle that’s very likely to fall for a hit. In Orr’s words:

What he truly excels in is a relentless, nearly unheard-of consistency. Arraez hits the ball well even when he doesn’t hit it hard.

Most of that is not on Arraez’s Baseball Savant page. And you can understand why Padres fans would be alarmed at sending away prospects to get a player whose page contains a whole lot of blue. They may have even been reminded of the Baseball Savant page of a Padres player with a similar style – one of the charts below belongs to Arraez, and one belongs to another Padres player:

The chart on the right belongs to Arraez, and the one on the left belongs to Tyler Wade. There are some superficial similarities, more than enough for social media to react strongly. It is true that Wade and Arraez have similar styles. But it is not true that Wade and Arraez are similar players – Arraez is simply much better at the thing they both do. Orr’s excellent analysis is correct: There are imitators, but only one Luis Arraez.

How does Arraez do what he does? As stats oriented as we usually are, we feel that one of the most valuable pieces of information on Arraez’s baseball savant page is this picture:

That’s an incredibly steep swing angle. The picture, of course, has since been updated, but we’re now seeing that unusual swing angle in a Padres uniform. Here it is in motion while still on the Marlins:

Hitters often use steep swings to get more power and lift (at the expense of more whiffs), but Arraez uses it to get whatever he wants. In the clip above, he inside-outed an up-and-in four seamer for an 81 MPH “line drive” with a launch angle of 11 degrees. That sentence barely even makes sense – that is not possible for most hitters to do regularly. But Arraez gets this type of hit with incredible consistency. Watch him handle the same pitch two games later:

That was an 88 MPH line drive with a 17-degree launch angle, and expected batting average of .910. These are not flukes – here’s another one:

A pitch that far inside shouldn’t turn into a line drive to left field. You can see where skeptics of Arraez sustaining success were coming from. But he never stops:

Arraez has been doing this for five years without missing a beat. These look like excuse-me swings because we are used to viewing a batter trying to do a certain thing at the plate, and that thing is hit the ball hard. But we’re in an era where we can quantify what makes him successful time and again, and we can conclude that we simply haven’t seen a hitter with this type of bat control in 20 years. And here’s the piece of evidence that makes it clear that Arraez’s approach is deliberate: He also has an A-swing:

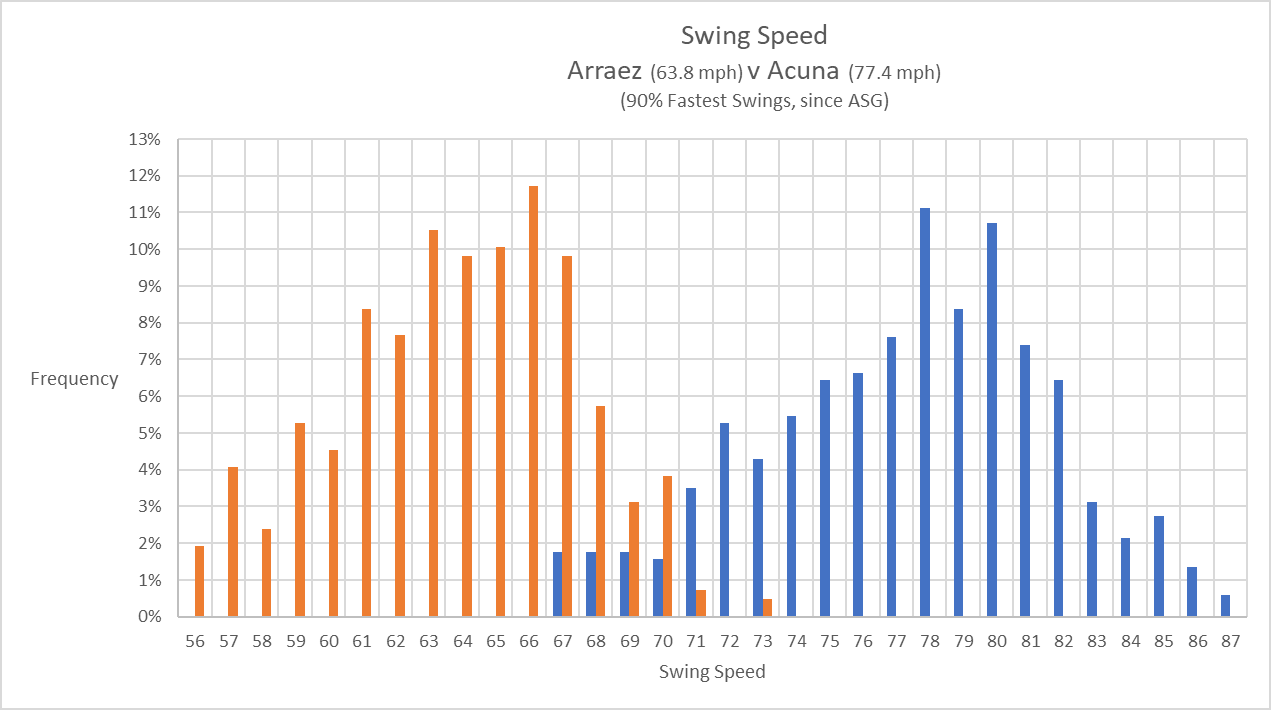

That’s an absolute no-doubter. And it came from a very different swing on a pitch in the same location, up and in. Arraez is capable of cranking up his bat speed, like he did when he clubbed two home runs against the USA in last year’s WBC. But he doesn’t do that often: His bat speed hardly ever gets above 67 MPH, which happens to be the very slowest bat speed Ronald Acuna was recorded at in 2023 (and that was probably a checked swing).

Graphic from Tom Tango

Something in that chart needs explaining. It’s pretty clear that when a player like Acuna, who swings hard every time, gets a swing 10 MPH slower than his average, something went wrong. Maybe the pitch fooled him, or he tried to check his swing.

But the variance from Arraez probably comes from him being in A-swing mode vs. not. Which makes for an interesting comparison between Acuna and Arraez with runners on base:

Here are Arraez’ splits with RISP, bases empty, or any runners on.

Arraez’s OPS with any runners on base is .904 for his career. And here are the same numbers for Acuna:

With any runners on base Acuna and Arraez have an identical .904 OPS. What jumps out is that Acuna’s production with runners on base is very similar to his production with bases empty. League wide it’s not uncommon for batters to see a 25-50 point jump in OPS with runners on base. But with Arraez you see a massive difference. He’s incredibly successful when runners are on base, his OPS is almost 160 points higher in his career, identical to one of the great power hitters in the game. It’s probable that the difference is just variance; his hits are mostly randomly distributed and there’s been a skew towards more hits falling with runners on base just as a matter of luck across his 845 plate appearances with runners on. But let’s entertain for one moment that Arraez hitting so much better with runners on base might have a little non-randomness to it. Let’s consider whether his success has to do with something that has been thought of as a myth by even the greatest hitters in the game.

We’re all playing baseball…

Arraez is often compared to hall of famer Rod Carew. That’s partly because they both played many years for the Twins; Carew is actually the all-time Twins batting average leader. In second place? Luis Arraez. And the names below those two aren’t exactly a bunch of bums.

Carew, Puckett, and Molitor are Hall of Fame contact hitters. The name on that list that most people won’t recognize is Lyman Bostock. Bostock was a beloved teammate of Carew’s who seemed destined to become an MLB all-star before his life was tragically cut short at age 27. Bostock was with the Twins for three years before moving to the Angels. When Bostock was scuffling early in the season with the Angels, Carew remembered giving Bostock advice:

When we played the Angels, he sent the batboy over to me with a newspaper photograph of himself wearing sunglasses with dollar signs on the lenses. Above the picture Lyman had written, Rod, I need help. His average was around .200. So I watched him in the game. I noticed he was lunging at pitches. He was too anxious. His swing wasn’t smooth, as it usually is. I told him I thought he was hitting the ball into “holes” between fielders instead of swinging with the pitch. No one can manipulate a bat so well that he can consistently hit the ball into holes.

For what it’s worth Bostock righted the ship after that advice and finished the season at .296. But the point here is the intuition of one of the best contact hitters to ever play the game was that no one can handle a bat so well he can consistently hit the ball into holes. If anyone could perfectly place the ball in a gap in the infield, it would be Rod Carew, but here Carew is basically saying “just try to hit it hard” So: Placing the ball is impossible… right? You begin to question these things when you watch Arraez play:

In real time this looks like just another hitter driving the ball to opposite field, taking what the pitcher gave him. But if you slow the video down, what you see is anything but ordinary:

Slow motion makes a few things clear. First, that is not an A-swing (to say the least). Second, there is no attempt to drive the ball at all, it’s all hands and wrists, there’s no follow through – it’s barely even a swing, he’s just sort of getting the bat in the ball’s way. Third, he did not seem to be fooled by the pitch, he’s not flailing or off balance, he looks locked in the entire way. Fourth, he’s not protecting the plate. The count is 0-1. There’s no reason to swing at that pitch other than to try to put it into play productively. But the normal way to do that is to drive the ball the way he normally does! By taking a swing! This doesn’t look like a baseball swing. What that looks like more than anything is a drop shot in tennis. It looks for all the world as if he’s deliberately trying to lob the ball over the drawn in third baseman which gave him an enormous amount of space in shallow left field to aim at… and that is not how the modern game is supposed to be played.

Carew is almost certainly right that no hitter is so good that he can consistently hit the ball through defensive gaps. But could a player have success hitting through gaps when the defense is positioned in an unusual way?

Arraez’ at bat came with two outs and a runner on third in a close game. A single in that spot is extremely valuable. Did Arraez see an open space in left field and factor that into his approach? If so, does he do that on a regular basis? Marlins announcers used to note that before stepping into the batters box, Arraez seems to scan the defense like a quarterback before a snap.

In order to evaluate whether a deliberate, tennis like approach to aiming swings at weak spots in the defense could be successful would require knowing exactly when a player is taking that approach and setting those at bats as the denominator. We never know where a player was trying to hit a ball (unless he’s bunting). Since we don’t have information on that captured in the box score or even Statcast data it’s just going to be another dot on his spray chart:

But evidence that a thing exists doesn’t have to be quantifiable. This is why the quote Arraez gave Kevin Acee on Thursday couldn’t be more perfectly timed with this article:

I watch the positioning when I go hit,” he said. “I look at third, short, second, the outfielders. If I see a hole, I want to hit the ball to the hole. Sometimes I hit, sometimes I don’t because I’m not perfect. But I just want to hit the hole every time.

What if it’s a mistake to evaluate him strictly as a baseball player using the Newtonian laws of the game. What if sometimes we’re all playing baseball while he’s playing tennis… This quote is Arraez stating that the phenomenon we think we see is actually the case some of the time. He’s clearly not always trying to hit into holes in the defense. Sometimes he’s just trying to hit the ball hard, like when he launches a no doubter to the second deck:

We’re not going to be able to quantify how frequently he switches to what we’ll call tennis mode. The best we’ll probably be able to do is to watch his eyes, watch his swing, and see where the ball ends up. Not very scientific. But it’s fun to consider that a thing we thought we knew – that nobody can consistently hit the ball through holes – might not be completely true…

Modern defensive strategies make this something worth wondering about. Wednesday in Cleveland, the Guardians had a runner on third with one out in a tie game in the bottom of the 11th. At which point, the Tigers decided to arrange their defense like this:

Five infielders, no center fielder. A team wouldn’t do this if they thought the hitter could control where they hit the ball – the hitter would obviously just dunk the ball into center field. The Tigers are betting that the “you can’t place the ball” theory is true. And, of course, one event couldn’t prove or disprove the theory, but here’s what happened:

We’ll never know if the ball going to center field was good luck, or if Rocchio altered something in his approach to make that hit more likely. But it’s an interesting thing to see. And you wonder if they would have considered such an alignment with Arraez up to bat…

When You Hear Hoofbeats…

When you hear hoofbeats you should think Horses not Zebras. To many, Luis Arraez is a singles hitter, and it’s natural to think he may be a similar hitter to an Adam Frazier or Tyler Wade. But he can do things these other hitters can’t. And much of this has been quantified: A nearly unheard-of consistency in hitting high quality, medium exit velocity line drives within a narrow launch angle that leads to lots of hits falling. Baseball analysts have been able to show that Luis Arraez is that elusive Zebra.

But there may yet be some unexplored dimensions to his game. He’s been, for his entire career, a different hitter with runners on base. A hitter with an absurd success rate. And that may simply be luck: his hits have happened to fall more often in situations where the defense has to play out of neutral alignment. Just dumb luck. This is the most likely explanation because common things are common. But by his own words he claims there’s more to it than that. And it really looks like in his first game with the Padres he saw a moment where he decided the best path to success was to drop his bat speed and exit velocity and aim a hit into left field. Something even the legends of the game felt no hitter could do with consistency… And Padres fans are going to have a front row seat in the search for the answer to a final question: what if when you hear the hoofbeats of Luis Arraez you shouldn’t think Zebra? What if those are the hoofbeats of a unicorn?

I believe there were fits of ecstasy tonight

As if to punctuate your point, after Friday night's game, Luis Arraez told The Athletic's Dennis Lin that he had planned to hit his game-winner exactly where he did hit it:

“I don’t try to do too much,” Arraez said. “I just be me there, and when I see the hole through the middle, I just say, ‘OK, if he throw me a pitch middle-middle, I want to hit to the middle.”