There can be no argument that another series loss to the Rockies, this time going 1-2 at Coors Field, is a disappointing outcome. And going 5-8 on the season is equally disappointing. And when disappointing outcomes happen it’s appropriate to look for reasons, processes that can be changed in order to get better results in the future. The thing is, going into Friday’s series opener it had been extremely hard to identify what processes the Padres could improve upon to have better success against the Rockies. This weekend’s series continued that trend, but there were few eye popping bad results that at least deserve a look to see if they were simply more otherworldly bad luck, or if there was an underlying process that can be improved.

Errors On Offense

What stood out most starkly from game one was the Padres grounding into an incredible four double plays to kill rally’s and end innings in a game they lost 7-3 but played well enough to win:

Earlier this year we wrote about the oddity of grounding into double plays:

Grounding into a double play is kind of like the “error” of the offense: subject to luck and not necessarily indicative of the player’s underlying skill, fluky and frustrating as hell.

Errors happen to good defenders and grounding into double plays happens to good hitters. Tony Gwynn led major league baseball in grounding into double plays the same year he hit .394 with a 1.022 OPS. Still, when a team does it four times in one game it deserves a look, so here is a breakdown of the double plays:

GIDP 1

In the top of the first Xander Bogaerts came up with the bases loaded and one out in a 0-0 game. The count ran to 1-2 and Cal Quantrill threw a splitter in the strike zone. Bogaerts put a competitive swing on it but grounded it sharply to third base.

Bogaerts has to swing at that pitch or it’s strike three. He didn’t fully barrel it up. But the part of the play he has control over, the decision to swing, was correct. And he took an A-swing which is also a good decision. We know Bogaerts can mode switch to a contact first approach, but this was the first inning of a game at Coors field where it’s likely many runs will be needed to win and it makes little sense to try to play small ball. The defense was aligned to keep a double play in order while preventing hard hit balls from getting out of the infield. Strategically the right decision is to try to drive the ball as Xander did. He just didn’t execute. It’s pretty hard to say there was a process problem here.

GIDP 2

After the Rockies put up six runs in the first two innings off Matt Waldron. Manny Machado came up in the top of the 3rd with a runner on first and one out. He worked the count to 3-1, the quintessential power hitter’s count. Quantrill delivered a sinker in the zone and Machado swung at it. He managed to hit it 104.9 MPH off the bat, but with a -12 degree launch angle that turned it into a tailor made double play ball.

Down by many runs early in the game the right approach to take is to drive the ball. And swinging 3-1 at a pitch in the zone and hitting it 104.9 MPH is doing a lot of things right. But it’s fair to say the swing looks a little awkward. And as Jeff Sanders wrote, Machado did feel a little off at the plate during the game, and discussed making adjustments going into Saturday:

Not really feeling myself and just really bad at-bats (on Friday). So … coming in here trying to make an adjustment on just putting the ball in play, playing to the field and playing to how this guy (Kyle Freeland) was going to pitch… Just trying to have good at-bats and be better than I was (Friday).

It’s probably safe to say there was something off with Machado at the plate on Friday. But it’s also hard to say that that is something Machado can just decide to change like flipping a switch. He would go 4 for 4 the next game which is a tremendous turn around. And he surely made some adjustment. He went the other way on all four hits. But it’s interesting to look at one of his hits that came on Saturday. With a runner on first and one out in the fifth inning Machado was down 1-2. He got a pitch up and out of the zone but swung at it:

The ball goes into right field for a single because Xander Bogaerts was running on the play and second baseman Brendan Rodgers has to move out of position to cover a potential throw to catch the runner trying to steal second. Without the runner going on the play that’s a tailor made double play ball to the second baseman, eerily similar to the one he hit the night before. Grounding into double plays is a lot about luck. Batters who hit the ball hard tend to ground into the most double plays. It’s a cost of doing business. But, there might have been something different going on on this play. As you can see on this alternate angle and hear Mark Grant discuss:

This might have been a hit-and-run play, a play designed to pull the second baseman out of position and let the right handed hitter slap a groundball the other way with a very high chance of going for a hit. Arguing for this is the fact that Machado’s swing was one of the slowest at 70.9 MPH, and shortest with a swing length of 6.7 feet, of the season. For reference Machado averages an elite 75.1 MPH bat speed and has gotten up to a ridiculous 85.5 MPH bat speed in big moments this season. The ball was also way up and out of the strike zone, a strange pitch to swing at even with two strikes, and even stranger to turn it into a ground ball the other way. There may have been some intent behind Machado’s swing, a deliberate process. Mark Grant thinks so, but we can’t be sure. This would be one way to lessen the chance of grounding into a double play, but it’s fraught with a lot of other considerations and it’s not clear that going to a hit-and-run with your best power hitter up should be plan A.

GIDP 3

In the top of the sixth with runners on first and third and the Padres trailing 6-3 Ha-Seong Kim got a first pitch sinker in zone:

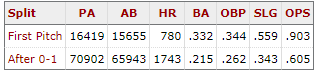

There’s an undeniable frustration that comes from a hitter swinging at a first pitch and grounding into a double play; it evokes impatience. But it’s fair to note a few things. First, it’s a really good pitch to hit. It’s an elevated fastball that Kim appears to time up perfectly. And he hits it hard. It just goes right to the third baseman. Hitters generally do very well when they swing first pitch. In 2024 the league has a .903 OPS on first pitch balls in play and more home runs have been hit on the first pitch than any other count (not the highest home run rate, the highest total number of home runs):

But what’s really telling about whether swinging at a first pitch strike is to compare outcomes after a batter reaches an 0-1 count, which would have been the case had Kim taken the strike:

Getting strike one is a big win for a pitcher. The OPS drops tremendously. This a very powerful argument for a hitter swinging at a first pitch strike when its a good pitch to hit. Once again, the problem here was execution, the outcome. The underlying process looks ok.

GIDP 4

Down 7-3 in the ninth with runners on first and second Jurickson Profar worked the count full to 3-2. Closer Victor Vodnik challenged him with a four-seam fastball in the zone:

This doesn’t need a lot of analysis, the problem was simply execution. The pitch was a good one to hit, and Profar appropriately swung. The result was just bad.

Four double plays in one game is extremely bad. And there can be no doubt this played a big role in the Padres losing game one. But the question of what can be done about it remains pretty unclear. Machado seemed to avoid grounding into another double play on Saturday because a runner was in motion, it might’ve just been luck, or it might have been a hit-and-run, something that’s very hard to replicate time and again and entails serious tradeoffs. It really just seems like the four double plays were another bit of confounding, stupendous luck for the Rockies. The things the Padres have control over, the swing decisions, appear sound.

Running Into Outs

The other astonishingly bad result was the Padres running into four outs on the basepaths in game 2. Coors Field is the most favorable run environment in baseball. And there’s something to consider there strategically. In very favorable run environments the value of scoring an extra run is diminished, and the value of making an extra out is heightened. When there are diminishing marginal returns on scoring an extra run, and increasing marginal penalties for giving away outs, it makes sense to adjust the risk tolerance on the basepaths. When the Padres made four outs on the basepaths in one game it’s easy to presume that they bungled this calculus and were being way too aggressive. But that’s why it’s helpful to watch the games. Here’s how the four outs on the bases unfolded.

Base Running Out 1

In the top of the 3rd Bogaerts was on second and Machado was on first when this happened:

This looks like a ridiculous debacle, amateur hour. But you can actually see exactly why this happened from a different camera perspective. From behind home plate you can see that Xander fakes a steal attempt of third and then stops:

As discussed above this can have a lot of advantages for the hitting team because it manipulates the defensive positioning, typically forcing the third baseman to move to cover third base and the shortstop to move to cover second base with a left handed batter up. This creates an enormous hole in the infield defense. Faking the run limits the risk that the runner will be thrown out or a batted ball event like a caught line drive will lead to a double play. The problem is Bogaerts sold the fake steal so well that Machado starts to run to second assuming it’s a true steal attempt. This is what the trailing runner is supposed to do when there’s a steal attempt in front of him. Once Machado starts running you can see his head is down as he gets into a sprint, and then turns towards home plate to see if the ball was put into play. This is also fundamentally sound. The runner needs to know if the ball is put into play so he can make his next decision (freeze on a line drive, or move out of the way of a ball hit at him etc.). It’s only after this that he looks up and see’s Bogaerts’ attempt was a fake. You can see Bogaerts is moving back to second as the catcher comes up with the ball but stops as he sees Machado about to touch second. It becomes an automatic out if a trailing runner passes a lead runner. So Bogaerts kind of just stops and gets in a run down.

Bogaerts was a victim of his own success selling a fake steal. All of the key decisions that seal the runners’ fate take place in about one and a half seconds. It’s probably wise for the team to examine this play and determine how better to keep both runners on the same page. But fundamentally the problem here was a very convincing fake attempt fooled a Padres runner who did everything right after. You want the runners to have improvisational freedom to put stress on the defense. And preventing this from happening again without compromising the freedom is a challenge. It’s a little harder than just telling a player to not get fooled next time, or to not be convincing on a fake.

Base Running Out 2

Up by three in the top of the fourth inning with runners on first and second Profar hit a single to center field and was thrown out trying to stretch the play into a double:

Profar was out by about 4 feet or so:

That looks like a lot. Profar runs at about 26.4 feet/second when he’s full speed. So his calculus on being able to take second base was off by about 0.15 seconds. That’s an extremely small margin, and the identity of this team all season has included putting pressure on the defense by trying for the extra base. So we don’t mean to criticize this too harshly. But we’ll be slightly critical here because of what we said earlier: Coors Field is an extremely favorable run environment. And that dilutes the value of a marginal run. If Profar had stayed at first the base/out state would have been first and third and two outs, with a run expectancy for the inning of 0.51 runs. If he’d taken second the base/out state becomes second and third with two outs, a run expectancy of 0.6 runs. So he was chasing about 0.09 runs by trying to take second base. You can approximate the value of an out in Coors Field by dividing the average runs allowed by Rockies pitchers at home, 5.74 runs/game, by the 27 outs that make up most games and you get an out being worth about .212 runs. This is back of the envelope math but you get the idea; an out is worth so much more than the run value of an extra base in Coors that it just doesn’t make sense to try for the extra base unless it really looks almost risk free. And that’s why the third baserunning out is really interesting to examine.

Base Running Out 3

In the top of the sixth with the Padres up 6-0 and runners on first and second Xander Bogaerts hit a single into right field. Donovan Solano was on first and easily took second base and held up there, but the throw from the right fielder bounced away from the catcher and the pitcher backing up home plate prompting Solano to try for third:

The ball takes a perfect carom off the wall behind home plate and is back in the hands of the pitcher a lot quicker than expected, but by then Solano is committed and gets thrown out by several feet. If you watch the replay you can see that everyone including Machado standing by home plate thinks this was an opportunity to advance a base. It usually is. This was kind of the opposite of Profar’s decision. Usually when a ball gets away from a fielder and his backup it’s a free extra base. We certainly would have instinctively started running for third.

Base Running Out 4

In the top of the eighth with the Padres up 8-3 Jurickson Profar was on first base with one out and got picked off:

It’s very easy to see why he was picked off:

It was exactly as Profar was moving further towards second with his right foot off the ground, the foot that would need to be planted in order to dive back, that the pickoff attempt happened. Profar was caught wrong footed when the throw came and couldn’t get back to the base in time. Justin Lawrence is right handed and was facing away from first base so couldn’t see Profar taking his lead, but he couldn’t have possibly timed his pickoff attempt any better. So it was just immaculately lucky timing that Lawrence threw over when he did.

Or was it? Watch the pickoff attempt again and this time focus on Rockies catcher Drew Romo:

Romo has a clear line of sight to first base with the right handed Solano up to bat. As Lawrence comes set Romo holds a target but suddenly flips his glove down and Lawrence immediately spins and throws to first base catching Profar in the exact moment he’s stretching his lead towards second. It’s not immaculate luck that let Lawrence make a millisecond perfect pickoff attempt on a runner he physically couldn’t see. Romo signaled Lawrence for the pickoff as Profar was mid step. It was a set piece. It was the opponent getting one over on the Padres. This was superbly executed. This play would get a lot of runners out. But unlike the ground ball double plays and the confusion on the basepaths earlier in the game, this can be planned for. It’s possible to minimize the chance of getting wrong footed when taking a lead off first. You’ll see some runners make quick feints back to first with each step when they feel the opposing team might be trying to get a timing play on them. It’s possible to extend your lead towards second without ever letting your momentum wrong foot you should a pickoff throw come at a critical moment. This is a marginal consideration, but it’s mattered before in big moments. Perhaps even in the biggest moments. Famously Kolten Wong was picked off of first base to make the final out of game 4 of the 2013 World Series. You can see very clearly that he was caught with his momentum taking him towards second base:

This was not a set piece timing play called by the catcher, this was just Koji Uehara taking a good guess about Kolten Wong’s lead. Wong missed a big clue that this play was coming as articulated on the local broadcast of the play:

Courtesy MLB.com

The Red Sox leading 4-2 with two outs in the bottom of the ninth meant that Wong scoring had little bearing on the outcome of the game, and in these cases teams will typically forgo holding a runner on or reacting to a runner stealing in order to preserve the optimal defensive alignment to make the final out. The fact that the first baseman was holding a meaningless runner on was tipping the fact that the Red Sox were going to try a pickoff play. Had Wong recognized that it would have been trivial for him to adjust his lead to eliminate the chance of getting picked off.

These very small considerations can be enormous in the post season where every out is precious. And it’s the reason that of the all the strange bad plays over the weekend the Profar pickoff stands out as one where the process can and should be improved. Because the Padres intend to make the postseason. And they’re going to need to control everything that’s in their power. Because their opponents are going to do everything in their power to get them out.

Odd Symmetry

Losing two out of three to the Rockies once again seemed to happen in part because of things the Padres can’t fully control. But in an odd bit of symmetry they benefited from other events they couldn’t control. The Diamondbacks got swept at the hands of the Rays this weekend. Late Sunday Jeff Passan tweeted this:

Losing the Rockies series was a missed opportunity, but everything is still on the table.

Get Out

There was at least one play this weekend that suggests the Padres can make themselves a little bit better equipped for the postseason by keeping it front of mind. The rest is probably best just left behind. Coors Field is an absurd ballpark. Its cavernous dimensions leave outfielders responsible for covering a preposterous amount of ground. The thin air makes fly balls travel much further. Breaking pitching don’t break. Fastballs are straight. It’s not the place you should go looking for lessons on how to improve your play against the rest of the league. The most important thing to do when you have to play games at Coors Field is what the Padres did Sunday night. Get out.

A seven game homestand starts Monday against the formidable Twins and the desperate Mets. There are 37 games left to navigate a path to the postseason. Half the league is fighting for survival. The white knuckle ride continues.

In the Baserunning Out 2 section, wouldn't the run expectancy or the two situations already take the out into account? Comparing the run value of the out to the run differential of the two baserunning situations seems like it's double dipping on the value of the out.

Also -- and maybe this is getting pedantic -- but the value of a single out is hugely different depending on WHICH out it is. The third out of an inning is far more consequential than the previous two. So even if the comparison is sound, this seems like an instance where we're ignoring the specifics of the situation, which I know you've written about a bunch lately :)

i'd argue that profar stretching to second is actually the wrong decision in that scenario even if he had had a better chance of being safe. if he stays at first, bryce johnson is at third which would be a perfect scenario for profar to steal second on the first pitch of the next at bat. this puts extra pressure on a catcher making his major league debut and with two outs he may be tempted to throw to second which would allow bryce to break for home but even if he doesnt then you have second and third anyway