The Formula

Watching The Pieces Fit

The Padres are nearing their final form. The trade deadline completed a roster that had amassed a winning record despite significant weakness that constrained strategy on a night-to-night basis. The Padres now have the deepest bullpen and lineup in recent memory. This opens different paths to navigate the game script as the opponent, and whims of fortune, put various obstacles and opportunities in their path. The Red Sox series was instructive, a glimpse of how the new weapons may tilt the odds in the close-quarters combat of a short series.

Game 1

The Padres had an off day on Thursday, and Friday’s opening game saw Nick Pivetta take the mound with a rested bullpen behind him.

The Padres signed Pivetta away from the Red Sox this offseason after the Red Sox declined to offer Pivetta a multi-year deal, opting instead for a one-year qualifying offer. Pivetta may have been amped up to face his former team.

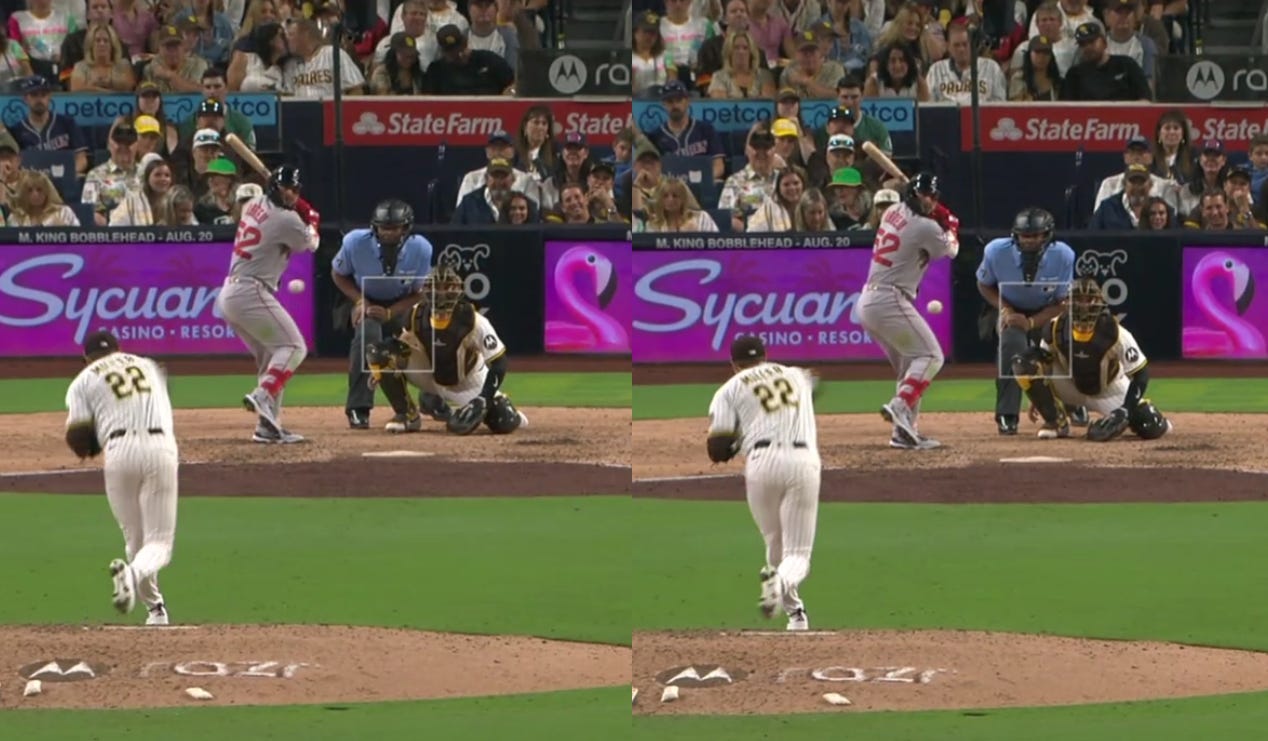

In the first inning Pivetta threw four pitches 95.1 MPH or faster, a feat he’s done only once this season in his April 22nd start against Detroit. His 95.7 MPH four-seamer to Roman Anthony in the first inning was his fastest pitch since June 4th:

His second fastest offering was to the next hitter, Alex Bregman, and here it looked like he might be overthrowing:

He navigated the first time through the order without sustaining damage, but things erupted in the 4th. Bregman singled to start the inning followed by back-to-back walks to Jarren Duran and Trevor Story to load the bases. After a sacrifice fly by Masataka Yoshida to score the first run of the game, Pivetta would compound matters with an errant pickoff attempt scoring another run. Wilyer Abreu would strike the big blow with a 2-run home run to give the Red Sox a 4-0 lead.

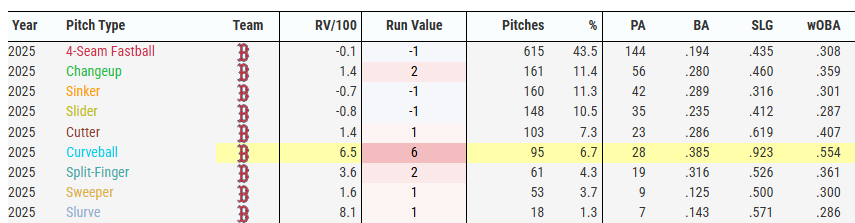

It’s interesting to look at Abreu’s at bats. Abreu is the Red Sox leading home run hitter, and in 2025 he’s been especially effective hitting curveballs:

In the second inning Abreu saw two curveballs:

The first curve was nearly unhittable at the top of the zone, but Abreu appeared to just miss the second curveball, flying out to end the 2nd inning:

In his next at bat Abreu saw three straight fastballs. He was late on the first, fouling it off, and watched the next two which were not very competitive offerings way out of the zone. The fourth pitch of the at bat was the third curveball Abreu had seen that evening. Pivetta missed badly with location and Abreu had it timed up perfectly, crushing it over the right centerfield wall:

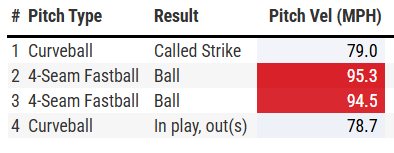

In Abreu’s final at bat he didn’t see a single curveball:

In this at bat Abreu was very late on the first three fastballs with a whiff and two foul balls. The fourth pitch was an uncompetitive splitter in the dirt. The fourth and fifth pitches of the at bat were four-seam fastballs that Abreu appeared to be finally timing up. This would be the classic time to mix in an off-speed to disrupt the timing. Pivetta did so, but the pitch call was another splitter. It got the job done:

Interestingly Pivetta has only thrown four splitters all season, and two of them came in this at bat. It was the first time Pivetta had thrown two splitters to the same hitter in the same at bat since 2022. He’d decided Abreu was not going to see another curveball all night.

Pivetta would complete six innings after 103 pitches. The Padres could not break through against Walker Buehler and trailed 5-0 at the start of the 7th. Despite every arm in the pen being available they went with Yuki Matsui for 1.1 innings, and brought in Sean Reynolds to finish the game. Reynolds struggled badly giving up five walks and five runs. But he let the higher leverage arms have another day of rest.

The 10-2 final did wonders for the Red Sox run differential, but didn’t really reflect a gulf in class. Sean Reynolds was optioned back to AAA to make room for Michael King after the game. The Padres decision to punt the game after the early innings deficit was about game planning for the rest of the series where there was reason to believe they’d need a rested bullpen to win.

Game 2

Saturday saw the return of Michael King after a nearly three month absence due to a nebulous thoracic nerve injury. King hadn’t pitched since May 18th. King returned to the rotation after making only a single rehab start in AAA, and was on a strict pitch limit.

King’s stuff looked intact, with velocities and pitch shapes similar to his pre-injury arsenal. What he struggled with was command, typically the skill that is the last to return after a long IL stint. He threw six pitches in the ‘waste’ zone:

Six pitches doesn’t sound like a lot, but that was 10.5% of the 57 total pitches he threw in the outing. For reference King’s pitches in the ‘waste’ zones on the season was only 6.6% of his total offerings prior to this outing. Occasionally a pitch is put in the ‘waste’ zone when there is a free swinger at the plate, but on Saturday it looked like all six were clear location misses. Again, control is typically the rustiest of the skills a pitcher struggles with in a return.

When King executed his pitches he looked just like the Michael King of old:

The last pitch of 2nd inning may have been his best, a bases loaded 3-2 changeup to Roman Anthony to get the final out and keep the inning from spiraling:

Anthony has the second lowest O-swing% in the league. King’s changeup was good enough to induce chase. He showed elite execution in the highest leverage pitch of the outing.

King was given the first batter of the third inning and got ahead of Alex Bregman 0-2 before Bregman turned on a changeup off the inner half of the plate for a double down the line ending King’s outing.

This was a proof-of-life outing for King. He’s rehabbing in major league games out of necessity, which is not ideal. King’s day ended after two innings, but this is something the Padres bullpen has been built to cover. And King looks healthy. He struggled in the expected ways. He should be better down the stretch.

Long Relief

With seven innings to cover the Padres went to Wandy Peralta next. Peralta’s outing was marred by three bizarre plays.

After Jarren Duran singled to put runners on first and third, Trevor Story hit a comebacker to Peralta. It looked like Peralta had a chance for a double play, but he opted to run towards Bregman on third to try to prevent a run from scoring:

It’s reasonable to try to preserve a tie but in the 3rd inning the decision to trade two outs for one was questionable. Not a terrible decision, but one that would be consequential.

Shenanigans

The next decision was not as defensible. Here’s what unfolded right after the play above. As the play ends you can see that Peralta raises his glove to receive the ball but doesn’t get it and turns to walk back to the mound without it:

As the broadcast cut back to the field a moment later you can see why:

Manny Machado held onto the ball after the play and walked back to his defensive position, even with the third base bag. This is the hidden ball trick. If the runner on third starts to take his lead the third baseman will tag him and it’s a live ball out. The key is that the pitcher is not allowed to touch the rubber on the mound without the ball, and the umpire felt Peralta had done just that and called the balk:

Runners are taught to stay put on the base until the pitcher toes the rubber to avoid the hidden ball trick (this is rarely seen in the major leagues but every player has seen it numerous times in lower levels of baseball). Peralta might’ve been straddling it, trying to deke Duran off third. It’s a bit hard to tell on the replay. But whether he did toe the rubber committing a rule book balk, or he was so convincing he fooled the umpire, the plan backfired terribly and another run scored.

Take The Easy Outs

The third bizarre play came next, Yoshida hit a tapper back to Peralta who attempted to field and throw home to get Story who’d been sprinting on contact:

Again, in early innings there’s an argument to be made to take sure outs when available. The Red Sox took a 3-1 lead thanks to some uncharacteristically sophomoric plays on defense.

Bogey goes ‘Boom’

The Padres sole run to this point had come from an interesting Xander Bogaerts home run:

This home run had an exit velocity of 92.3 MPH, about the speed of a Yuki Matsui fastball. But it was pulled right down the line. Pulled fly balls down the left field line in Petco are a cheat code in a notoriously fly ball suppressing ballpark. And he did it on an 0-2 pitch.

He would come through again in the bottom of the third with runners on first and second and two outs:

Bogaerts has been the victim of inflated expectations based on the enormous contract he signed1. But even at his nadir in production he’s been a net positive, a winning player. And of late he’s been far, far more productive. His two home runs in Arizona last week were the opposite of cheat code home runs:

Those were the first fly balls with an exit velocity over 105 MPH that Bogaerts has hit in 2025. It was this ability to hit the ball hard -in the air- that had seemed to abandon him for most of the season. And that had colored our pessimism about Bogaerts as a middle of the order hitter at this stage in his career. He showed last week that he still has that in his game. And he’s been enormously productive since the end of June. At his worst he was still a valuable player. And if the Padres can get his best once again it would be game changing. But even if he ends up somewhere in between, that’s a massive development for a team with these ambitions.

The Padres would end the 3rd still down by a run.

Wandy Peralta was asked to get through one more inning and was able to keep the score 3-2.

New Options

When the Padres failed to score in the bottom of the 4th this set up an interesting opportunity to compare the pre and post deadline strategy. With five innings to go this would normally have been a time to bring in another long reliever. But the Padres had the luxury of taking a different strategy with a much deeper bullpen. They brought in Jeremiah Estrada for the 5th. Estrada struck out two and retired the side on only 12 pitches.

The Padres were able to break through in the bottom of the 5th scoring two runs off of Lucas Giolito who was left in to face the top of the order for a third time. Fernando Tatis singled to lead off, and with two outs Jackson Merrill, Xander Bogaerts, Ryan O’Hearn, and Ramon Laureano worked back-to-back-to-back-to-back walks to score the tying and go-ahead runs.

Laureano’s at bat was particularly impressive. After working the count to 3-1, Laureano took a vicious swing at a high fastball, driving it foul down the left field line. With the count now 3-2 he fought off a very well placed four-seamer on the low outside corner. On the next pitch he didn’t chase a four-seamer on the low-inside shadow zone to draw the walk:

Laureano might be overqualified for the 7th spot in the lineup, but his presence is an enormous luxury.

With the one run lead the Padres asked Estrada to take the 6th. The Red Sox 7-8-9 hitters were due up, a lefty in Abreu and two right handers in Rafaela and Connor Wong. This time Estrada struck out the side.

With the score still 4-3, Adrian Morejon was asked to take the top of the Red Sox order, lefty Roman Anthony, righty Alex Bregman, and lefty Jurran Duran. Morejon struck out both lefties but Bregman reached on a single. And this is when the trade deadline strategy really started to come into focus.

WHO was pitching in the 7th?

The Padres brought in Mason Miller to face the right handed cleanup hitter Trevor Story.

Miller hasn’t pitched in the 7th inning of a game since 2023 when he did so four times, twice as a starter, and twice in long relief. But the game theory here is that one of the Red Sox most dangerous hitters was coming up with a runner on base in a one run game. Getting the out would wipe the slate and force the Red Sox to try to get a rally going with their 5-6-7 hitters the next inning. Miller was being asked to do fire brigade duty where a single out would set up a much easier next inning.

Miller’s sequencing was interesting. Story, geared up for the fastball, got three straight sliders to begin the at bat. He was fooled badly by the second and third offerings. Then, with Story having to cover the whole plate to account for the slider, Miller pumped a fastball up and in that made Story flinch. On the fifth pitch Miller zoned a fastball that Story was hopelessly late on:

Miller needed only five pitches to end the inning allowing him to take the 8th as well.

Miller made one bad pitch in the outing, a slider that hung over the inner half of the plate and was turned around by Masataka Yoshida into right field. A box-score invisible play by Tatis held this to a single.

Miller was electric the rest of the inning.

His pitch mix to the next hitter, Abraham Toro, was interesting. Miller’s first fastball was 99.2 MPH with 11 inches of horizontal break to the arm-side, an unusual shape for a four-seamer. For comparison that’s almost the identical amount of arm-side break Dylan Cease gets on his sinker. This was followed by a perfectly executed backdoor slider that Toro watched for strike two (you can hear Mark Grant’s admiration on the broadcast). After a second slider outside, Miller threw another fastball, this time a straighter 102 MPH four-seamer with 17 inches of induced vertical break for the strikeout. Here’s the whole sequence:

During the at bat the Red Sox pinch ran the very speedy David Hamilton who attempted to swipe second base. Xander Bogaerts was able to steal an out by holding a tag well after the initial swipe and catching Hamilton briefly losing contact with the bag which was caught on the replay challenge:

Before replay challenge there was little reason to consistently apply tags this way. But in the modern game it’s a new fundamental.

Wilyer Abreu was the final batter Miller faced. Miller put Abreu in the torture chamber. The first pitch was a 102 MPH four-seamer at the top of the zone with 17 inches of induced vertical break and 10 inches of arm-side run (four-seamers are not supposed to move like this). But the second pitch of the at bat was the most interesting, a 95 MPH changeup that broke 17 inches to the arm-side while dropping 26 inches. Stephen Kolek was a successful development for the Padres in large part because of his sinker, which averaged 93.5 MPH with 16 inches of arm-side break and 27 inches of drop. Miller is a one-of-one pitcher, and he followed the changeup with a 103 MPH four-seamer with only seven inches of drop due to 18 inches of induced vertical break. Abreu could not catch up. Here’s the sequence:

Here’s the tunnelling of the first two pitches, the four-seamer and changeup, which were on a nearly identical plane out of the hand:

But watch the two-plane separation:

The pitch mix forced Abreu to account for the entire strike zone, and of course the thought of the slider had to be in the back of his mind as well.

It’s this pitchability, in addition to having the most elite stuff in the league, that made Mason Miller (and the four and a half years of control) an arm worth trading top tier prospects for. It’s also why there’s belief he could be an elite starter.

The final pitch to Abreu was interesting for another reason. Watch how Freddy Fermin sets this pitch up:

Fermin crouches comically low and inverts the glove, projecting a breaking ball incoming. With his throwing hand he surreptitiously indicates he wants the ball up, and just before Miller starts his wind up he flashes the true location call. This sort of misdirection comes from an understanding that at all times opposing hitters, and indeed the dugout and base coaches are looking for information about the next pitch. Hitters peek at a catcher’s setup, runners on base relay pitch grips, the dugout and base coaches try to pick up on tells from the pitcher’s posture, arm positioning, the cant of his glove, and countless other subtle giveaways. This is an ancient, box score invisible, part of the game. Even Padres hitters have been accused of peeking in the past. Few teams are better, or more committed to this than the Red Sox as would become clear in the 9th. Fermin is just offering up chaff to confuse their radar.

Just like that the one run lead was stretched from the 5th inning to the 9th with little doubt it would be preserved. This is a formula that only a uniquely deep bullpen allows.

Closing Time

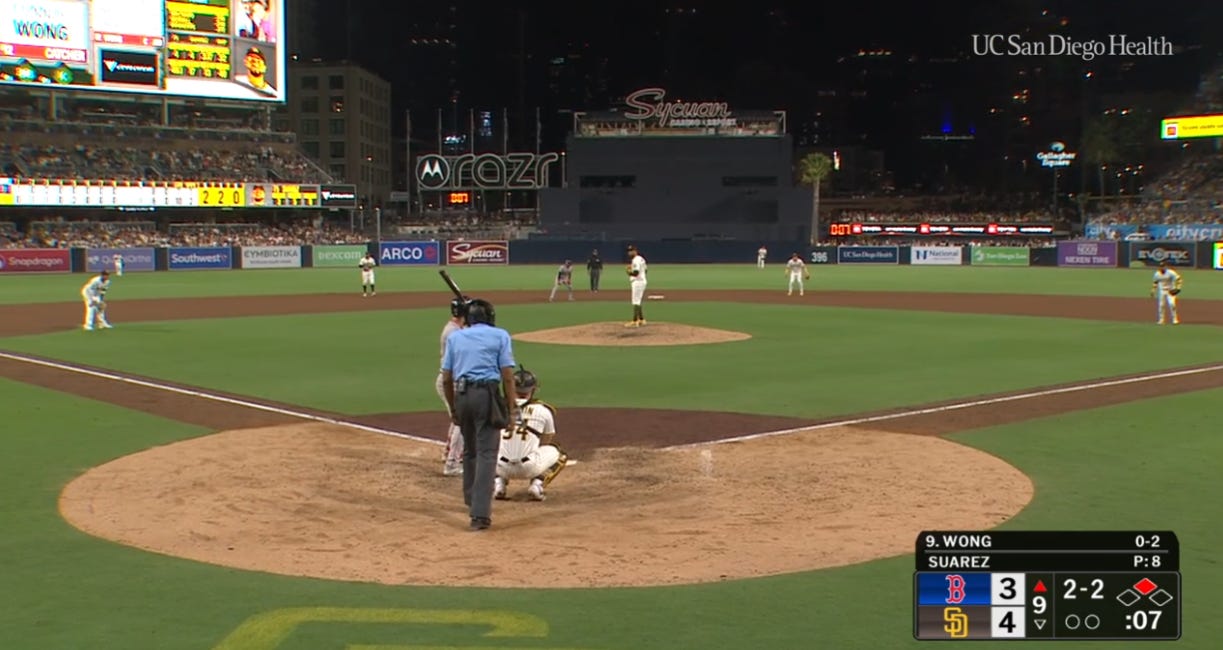

The Padres still clung to a 4-3 lead entering the 9th. Robert Suarez was brought in to attempt his 33rd save of the season. He immediately fell victim to some bad batted ball luck. On a 1-2 count he got Ceddanne Rafaela to weakly roll over a changeup, but the result was a perfect swinging bunt that the blisteringly fast Rafaela beat out for an infield single:

Rafaela would swipe second base easily, putting the tying run in scoring position for Connor Wong.

Wong had fallen behind 0-1 before two very generous calls ran the count to 2-1. Wong would try to bunt Rafaela to third on the 2-1 count but rolled it foul to bring the count to 2-2. It was interesting to contrast the fielding dynamics when the count went to two strikes after the failed bunt attempt. On the following pitch the Padres continued to play the corners in presuming Wong would try to lay down the bunt again even with two strikes:

But on 2-2 Wong swung away, fouling the pitch off:

Seeing this, the Padres moved the corner infields way back to prevent a game tying single from getting through:

Wong would work the count full and foul off the first 3-2 offering before strangely staring at a perfect strike three:

There’s no way to know whether CB Bucknor’s protean strike zone distorted Wong’s swing decision, but it’s possible it contributed:

With one out, lefty Roman Anthony was up. He spit on a first pitch changeup on lower edge of the zone that was called a strike (this time):

On the second pitch he squared up a high fastball for a ground rule double which tied the game:

Alex Bregman was up next, and Ruben Niebla came out for a mound visit. It was interesting to see how the Red Sox took advantage of the game break:

Roman Anthony ran off the field from second base to review images on an ipad and the camera panned to what the Red Sox were having him review:

As the camera cut away you could see the images were the side by side of Suarez’ setup for the fastball and the changeup:

This is what a second base runner can see, and if a pitcher has an idiosyncratic difference in setup for a pitch, that runner can relay the coming pitch type to the hitter. This is perfectly legal. The Red Sox and Astros were caught illegally using electronics to steal signs in real-time (the key distinction) in 2017 and 2018 respectively (incidentally the years those teams won the World Series). But you can see from the brown jersey Suarez is wearing that these images were from a different game. The league confirmed that this was a registered iPad and its use is permissible in game.

Suarez stayed in to pitch and was able to retire Bregman for the second out. An intentional walk was issued to lefty Jarren Duran to get to the more favorable matchup with righty Trevor Story. Suarez struck out Story to end the threat.

The Padres came up empty in the bottom of the 9th sending the game to extra innings.

The hope had clearly been to get Jason Adam a night off, but he was available, and was brought in for the top of the 10th to try to strand the Manfred man and preserve the tie.

Because of the earlier pinch running substitution David Hamilton was batting instead of Masataka Yoshida. The Red Sox asked Hamilton to lay down a sacrifice bunt. And he struggled:

Hamilton might have made things harder for himself by trying to have his cake and eat it too; trying to give himself a chance at a single rather than a pure sacrifice. He’s not in a classic sacrifice bunt approach, seeming to move towards first right at the moment of contact.

Adam’s changeup has so much movement that each time Hamilton’s attempted to bunt the bat was head moving as he tried to track the movement of the pitch.

Hamilton’s fouled bunt strikeout was a devastating blow to the Red Sox chances.

Adam was subsequently able to induce weak contact from Romy Gonzalez and Cedanne Rafaela to end the inning and keep the Red Sox from scoring.

The Butcher Boy

To start the bottom of the 10th, with Bogaerts as the free runner on second, the Red Sox opted to walk Ryan O’Hearn. It was the fourth walk for O’Hearn who’d taken terrific at bats all night. This brought up Ramon Laureano, and it’s clear the Red Sox expected him to bunt. Laureano took advantage of this:

It might seem like this is just batted ball luck, but it’s not. Not entirely. There’s an old play in baseball called the Butcher Boy. Casey Stengel coined the phrase based on the downward chopping swing a hitter takes to execute a high bouncing ball down the line to a drawn in third baseman. The classic version of the play is to show bunt in an obvious sacrifice situation to draw the third baseman in, before quickly switching back to a choked up swing to try to punch the ball past the defenders drawn out of position:

But in the 10th inning Saturday there was no need to show bunt because the Red Sox, having thoroughly scouted the Padres tendencies, knew that Mike Shildt calls for a bunt in this situation nearly every time. As the pitch was being delivered Alex Bregman was only 77 feet from home plate:

And Laureano took a measured 66.2 MPH contact swing to smack the ball into the ground down the line:

This is a tailor made double play ball if the infield is in normal alignment. But they weren’t. And that’s the idea behind the butcher boy. Batting a ball into the ground carries a much higher likelihood of getting through a drawn in infield. This is one of the old ways. And it’s not clear this is what Mike Shildt wanted Laureano to do:

This is a play high school coaches teach, especially to their less capable hitters. It just doesn’t happen in the era of the universal DH. But it used to be seen from time to time at the major league level with pitchers that could handle the bat a little.

Zack Greinke famously executed it during the 2014 NLCS:

Gerrit Cole got one of his two lifetime doubles on a butcher boy play:

Pitchers don’t have elite bat control and although the plays above were successes, hitting the ball in the air defeats the purpose of the play.

Maybe it’s not surprising then, that Laureano, an excellent hitter, executed perhaps the most impeccable, textbook version ever seen at the major league level.

There will be many questions about the optimal way to manage games like this, especially the decision to bring in the team’s most dominant reliever before the 9th, and the continued use of trick plays and strategies from the old ways. It’s good to question these things. And it’s not clear they were the right decisions. But it’s not a bad thing to have them in your back pocket either.

Game 3

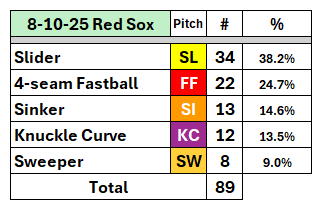

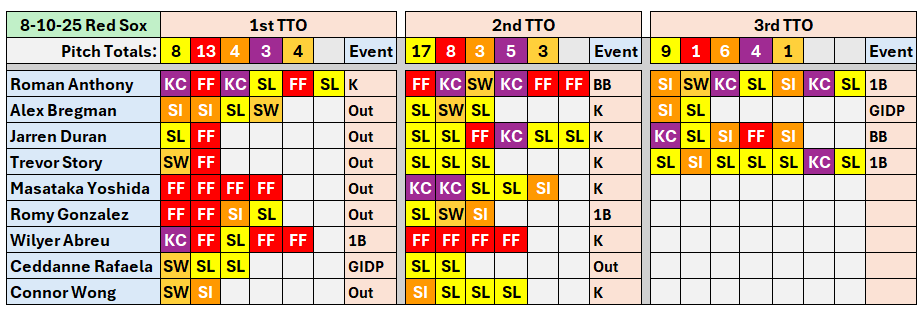

Since no high leverage arms were used in game 1, the Padres could still have gone to any/all of their bullpen for game 3. But they didn’t have to. Dylan Cease was exceptional on Sunday. And for the fifth straight game since the All-Star Break he varied his pitch mix significantly:

He kept hitters guessing subsequent times through the order:

He threw more sinkers (13) than any game this season. And he shut down the fourth best offense in baseball.

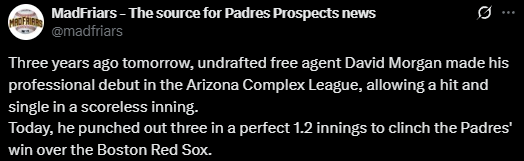

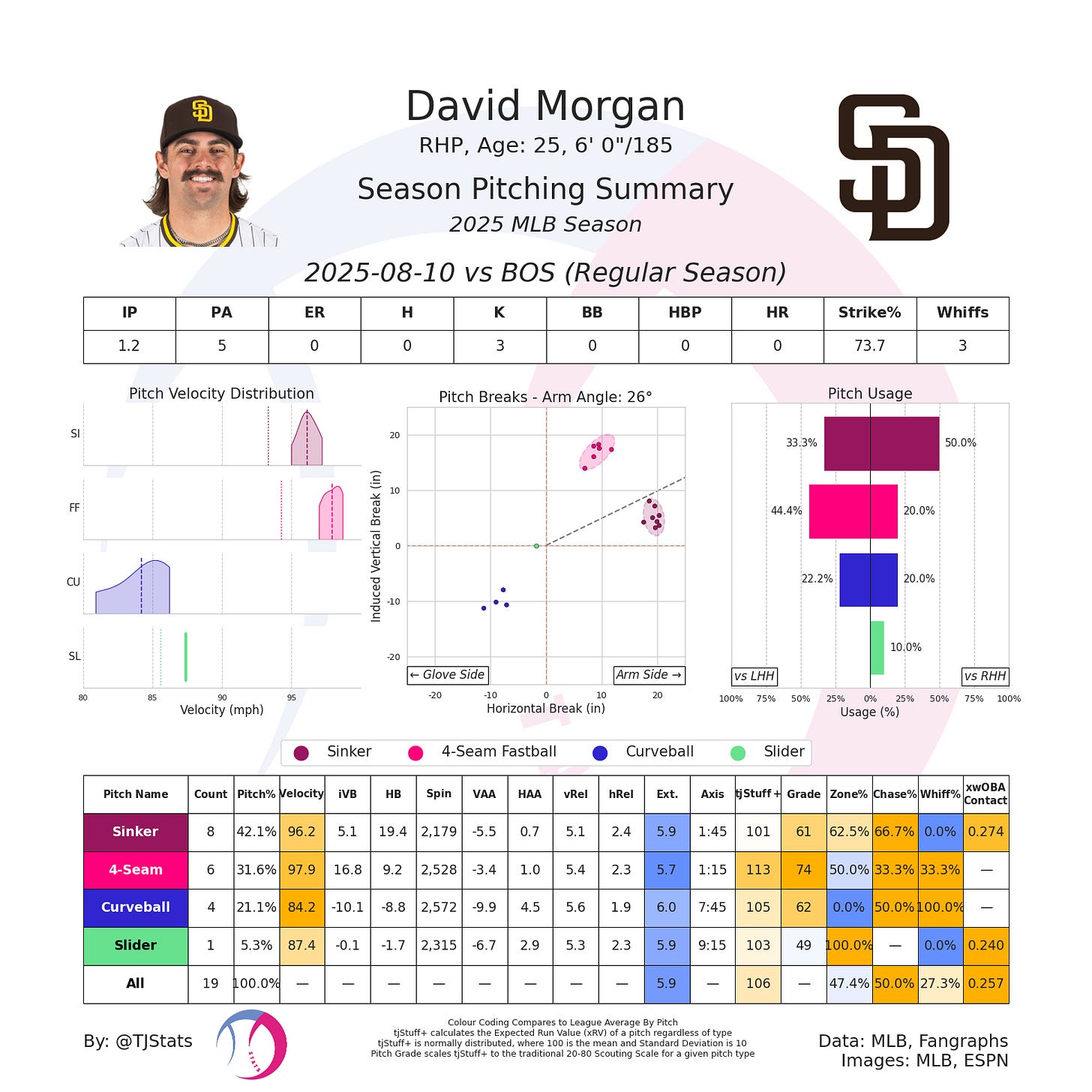

The Padres used two high leverage arms to extinguish the only real threat the Red Sox made in the 7th after an error cost the Padres a double play and allowed two runs to score. But they survived the inning with Adam and Morejon putting out the fire before David Morgan came on for a five out save. Morgan’s development has been an incredible success story for the Padres:

And he’s not doing it with smoke and mirrors:

These are very interesting pitch shapes and release points. You can see the movement he gets on his breaking pitches, and the stark difference between the fastballs: a run-and-drop sinker vs a high ride four-seamer from a very low release:

Video Courtesy: @TooMuchMortons_

Morgan’s ability to close out the game gave precious rest to Mason Miller, Jeremiah Estrada, and Robert Suarez.

Toughest Stretch To Come

The Red Sox series showcased the many different ways a roster this complete can be deployed. There is no longer one win formula. There are multiple paths to take. Unique options. And the Padres will need them. They’re entering by far the toughest stretch of the season with 13 games against the Giants and Dodgers over the next 14 days. How they do through that gauntlet will define their postseason outlook. It’s daunting, to be sure. But they’ve never been more prepared.

Contract Derangement Syndrome (CDS). See: Soto, Juan, New York Mets

If Buehler didn’t turn back into his Dodger lovin’ self we might’ve had a sweep this weekend. Great series overall and an excellent showcase from the newcomers. Laureano seems like a DAWG. Gritty, plays hard, does what the game calls for (or doesn’t lol). Love seeing Bogey continue to swing a hot stick. And man, David Morgan is this year’s Jeremiah Estrada. It’s possible when Suarez opts out Morgan could slot into a true high leverage role next year and the bullpen could somehow be even BETTER.

Thanks as always for the incredible analysis!

Wonderful work as always, thank you for what you do for us fans!

I was wondering about that Miller 99 as well. When I saw it in the moment I got worried for a second that his velo was dropping (and maybe an injury coming), but was relieved when he was back to 102-103 after that. Do you think his 99 with horizontal movement was actually him throwing a sinker intentionally?

I was in love with that 95 changeup. Feels like if he went 33% each on his fastball/slider/changeup, he'd be truly unhittable. But add in that 99 sinker too? Oh lord.

What do you think his ideal pitch mix+usage would be (as a reliever v starter)?