You don’t incur the loss of perhaps the league’s best hitter, best closer, and Cy Young award-winning starting pitcher and come out the other side with more talent. The 2024 Padres will start the season with less talent than the 2023 team. It’s easy to look at that, and the forcefully underwhelming 82-80 record of that star laden/star crossed 2023 roster and presume the 2024 Padres will be mediocrity incarnate. After all, if the 2023 team couldn’t make the playoffs with a bumper crop of talent, why should a thinner harvest lead to a better result?

Well, collecting talent is part of the winning equation, but talent does not automatically lead to value – if it did, the ’23 team might be receiving their World Series rings right now. Extracting value from talent involves other inputs. Games take place in the real world where context matters. How that talent is deployed adds a multiplier or diminisher effect. Throughout 2023, we all had the sense that there was some diminishing effect on the talent the team had accumulated, preventing the expected value from accruing. Some illusory cooling force. How much of that was luck and how much was culture is impossible to say, but it would be foolish to dismiss culture as a cause. And culture – unlike luck – is something the team can change.

The Quiet Part

It might be hard to visualize how culture might have any impact on winning in a game where every player is individually motivated to play well. But if there is one thing that the 2023 Padres season and offseason proved once and for all, it’s that culture can impact winning, and we’ll attempt to show how.

Josh Hader recently did an interview with @FoulTerritoryTV, and it’s pretty incredible. The clip is three minutes long and we suggest you watch the whole thing.

Hader made it clear he was not willing to pitch in circumstances that were not rewarded in the market. The Hader House Rules were real. Hader is such a good pitcher that it’s easy to feel that it’s worth accepting the special rules in exchange for the dominance he brings when the stars align and he’s available for an important game. That’s probably true as far as winning games in a vacuum goes.

We’re not villainizing Josh Hader; his actions were a rational response to the (extremely) unfair treatment he received from the Brewers and the arbitration process. But culture is supposed to provide a counterbalance to the individuals’ selfish impulses. Individual incentives don’t always overlap with organizational incentives, which creates a problem for the organization. And, at least as it pertains to Hader, it’s clear that the culture of the ’23 season didn’t bring all members of the team into alignment around the singular purpose of winning games. Josh Hader, to his credit, was more honest about this than any athlete we can recall speaking about such matters. He said the quiet part out loud.

Goliath Strategies

AJ Preller knew about the Hader House Rules. He knew Hader would be unavailable for important games in 2023. And he planned accordingly. He lavished a contract on Robert Suarez that paid him as if he was a closer. He wasn’t just paying Suarez to be the closer who succeeds Hader -- he was paying him to be the co-closer for crucial games in 2023 where Hader would be unavailable. AJ planned to have a second closer – Suarez -- ready on those nights. The strategy was sound, but it was derailed by the catastrophic injury Suarez suffered. Of course, this move was part of the Padres’ effort to hang with the big spenders of the league: They sought out the best players that money could buy and fielded a top three payroll. They focused on getting the top talent in key roster positions and presumed that value would flow from there. When one of the stars had idiosyncratic rules that ran contrary to the team’s goals, they spent more on talent to make up the gap. This is the Goliath strategy: you can accept the idiosyncrasies of star players because the sheer volume of talent on the team should lead to success. What AJ Preller might have underestimated was the impact special rules – which prioritized maximizing one player’s market value over the team’s needs -- might have had on organizational culture. There are many examples where the optimal strategy to win may require a personal sacrifice from the player. Starting pitchers don’t want to be pulled before the fifth inning. Star players want to play their preferred position. “Productive outs” damage a player’s OPS. We could go on. The point is: Once you prioritize one player’s individual needs, it’s not clear where the accommodations stop.

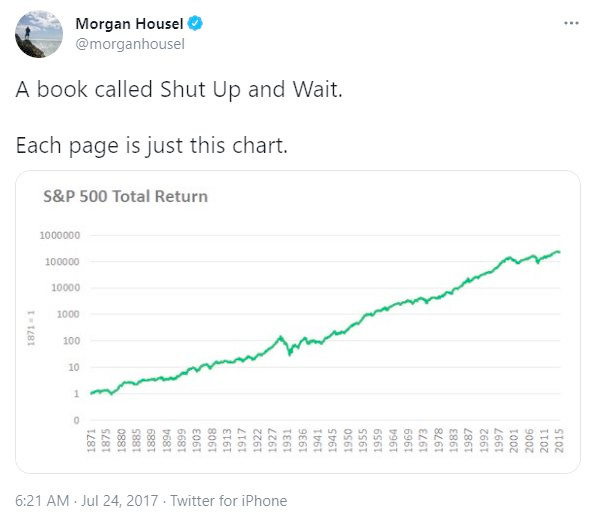

The Goliath strategy is probably deader than, well…Goliath. That’s not just true because the team’s payroll has contracted: It’s also true because no team can compete with the Dodgers in terms of traditional talent acquisition avenues. The contract that Shohei Ohtani agreed to, a 10-year, $700-million-dollar deal, with Ohtani deferring $680 million until after the contract expires in 2033, is not something that can be replicated. The contract structure was interpreted by the league to equate to an AAV of ~$46 million using a 4.43% discount rate, which is pretty close to the risk free rate at the time of the signing. This is good for the rest of the league because it’s a higher AAV for the Dodgers against the Competitive Balance Tax, but in terms of a real world estimate of the value Ohtani gave up, it’s laughable. Even a middling portfolio manager could surely get Ohtani something close to the 10 percent return that the S&P 500 has been getting for over a century, which means that Ohtani gave up a…well, Goliath-size chunk of money.

The point here is that no other team can convince the best player in the game to give up enormous amounts of personal wealth to permit more present day spending on a competitive roster with any regularity. The Dodgers won the offseason. You’re not going to beat them at that game. They are, in reality, the only team playing that game.

The Padres can’t beat the Dodgers at the Goliath game, but luckily that’s not the goal. The goal is to beat them at baseball. And that starts with getting every ounce of value out of the lesser pool of talent the Padres have acquired. That means fixing the broken culture of 2023. We’re going to take the discussion a step further. Psychologist Edgar Schein was particularly gifted at describing the machinations of organizational culture, especially in his identification of shared basic assumptions that make up the essence of the culture. He wrote:

Basic assumptions, like theories-in-use, tend to be nonconfrontable and nondebatable, and hence are extremely difficult to change. To learn something new in this realm requires us to resurrect, reexamine, and possibly change some of the more stable portions of our cognitive structure…Such learning is intrinsically difficult because the reexamination of basic assumptions temporarily destabilizes our cognitive and interpersonal world, releasing large quantities of basic anxiety.

Rather than tolerating such anxiety levels, we tend to want to perceive the events around us as congruent with our assumptions, even if that means distorting, denying, projecting, or in other ways falsifying to ourselves what may be going on around us. It is in this psychological process that culture has its ultimate power. Culture as a set of basic assumptions defines for us what to pay attention to, what things mean, how to react emotionally to what is going on, and what actions to take in various kinds of situations.

Here it’s important to remember that the Padres’ culture is embedded within the deeper culture of baseball. And that culture includes deeply ingrained assumptions about the way the game should be played. To try new things, you have to have a culture that accommodates trying new things. And your culture should prioritize winning above all else. And now, the team culture should also include finding non-traditional paths to winning, since the roster has less talent than it did 12 months ago.

But how? Here are some examples of how the Padres can improve their results through cultural shifts.

David Strategies

The Goliath strategy is to accumulate the most top talent and then pursue standard strategies to winning. But a David strategy has to seek out unconventional strategies. This offseason, John Precoda and Raphie Cantor of Pads Above Replacement discussed how the Padres might extract incremental value from their existing assets:

Thankfully, the 2024 Padres appear pretty strong on the front end of the starting rotation. From the 13:30 - 16:30 mark in the video above, John Precoda describes exactly how to create incremental win probability through unconventional strategic choices around the back end of a starting rotation. Precoda notes, for example, that in 2023, Michael Wacha and Seth Lugo had a 2.63 ERA in 219 innings when facing the opposing team the first two times through the lineup. But this ballooned to an astounding 7.31 ERA the third time through. Those disastrous third-time-through runs amounted to 60.1 innings, and if those innings had been pitched by relievers pitching to a 4.00 ERA, the Padres would have saved 22.2 runs. That’s about 2.5 wins -- that's a free Josh Naylor just from better bullpen use. League-wide, ERAs tend to inflate to about 5.20 the third time through the order. It should be easy to find commodity relievers that can put up better than a 5.20 ERA, especially because the Goliaths won’t be looking for them.

But there’s a catch: For a team to actually do this – to not let their starter go through the order a third time – it would require a major deviation from baseball norms. Starters would not be happy being pulled in the 3rd and 4th inning. Some days, a starter who was cruising would get pulled, and the bullpen would get shelled, and the complaints on talk radio the next day would be audible on distant planets. Managers would be understandably reluctant to go that nontraditional route. Goliath strategies get less scrutiny because the default belief is typically that the game was being played the right way. David strategies are riskier, but that’s sort of the point. Relatively resource-poor teams have to find novel ways to compete, which entails risk, and executing that strategy requires a culture that permits it.

Analytic Adumbrations

When we were kids watching baseball, we all knew there was a lot more going on than just what showed up in the box score. Like when Steve Finley robbed a home run or that time Chris Gomez knocked down a ground ball destined for left field just enough to keep it in the infield and prevent a run from scoring on the play. Those plays just showed up as a put out and an infield single, respectively. Maybe Jerry Coleman would hang a star for Finley, but baseball statisticians wouldn’t. No doubt, many dismissed such phenomena as randomness with no statistically significant value. Until someone gave it one. Enter Defensive Runs Saved. DRS is not a perfect stat by any means, but the concept is laudable and long overdue. Shouldn’t we be trying to quantify the previously unquantifiable? Hasn’t baseball been doing that for about 150 years now?

Last year, the Padres badly needed novel approaches that maximized value. Baseball has been transformed by the analytics revolution of the early 21st century, and skills that maximize run production over the course of a season (like OPS) have marginalized skills that produce runs in specific situations (like situational hitting). Because productive outs damage OPS, and OPS is what most teams seek, it’s hard to get players to embrace situational hitting. This is compounded by the fact that some analysts insisted that all situational hitting variations are flukes. We discussed this in an article called “Baseball’s Monty Hall Problem”. Essentially, early in the game, a team does not know how many runs it will need to win the game, so it’s rational to optimize around the strategy that scores the most runs over infinite iterations of that inning (the Goliath strategy of pursuing OPS monsters). But late in the game, when a team has gained knowledge and knows precisely how many runs it needs to win the game, it makes sense to switch to a situational approach that maximizes the chance of scraping across that game-winning one run. This offseason, Bill James – the father of sabermetrics – took to Twitter to opine that situational hitting might be real, after all.

Even the most respected minds in baseball have blind spots. We know that hitters face a fundamentally altered hitting environment with runners on base, which changes the expected pitch mix and location. How likely is it that all hitters perform exactly the same in this situation as in a bases empty scenario? It’s probably true that in the pre-analytics period, far too much importance had been placed on situational hitting – the idea that certain guys were “clutch” (in the traditional ice water in the veins vs butterflies in the tummy sense) was basically a myth with roots a hundred years deep. The belief in things that weren’t real led to irrational decisions. But that pendulum has swung so far in the other direction that the notion of “clutch” – which doesn’t appear to be real – has been conflated with the idea that some hitters’ skillsets are better suited for certain situations, which does appear to be real. Simply put: Situations matter. Not all runs are equal in terms of their impact on win probability, and we should no longer pretend that they are. We should be clear-eyed about the new biases that have set in after the first wave of Sabermetrics. That Bill James can speak to this after 20 years of the world believing his work had cracked the baseball code and created almost Newtonian laws of the game is a sign of a really strong intellect, interested in furthering the understanding of the game. Maybe it cost him some personal pride, but we actually think that level of intellectual humility is admirable. Respect, Bill James.

The idea that there may be signals buried deep within the noise should be a loadstar for David-strategy teams like the Padres. How likely is it that MLB hitters – who have otherworldly hand-eye coordination -- are completely unable to demonstrate proficiency in sacrificing power for contact when the situation calls for it? There’s some evidence that motivated players can limit their swing and miss, and they do it by trading power for contact:

That’s a modest difference, but it’s not nothing. And if there is a big gap between players who can alter their swing to make contact and players who can’t, that could be a real skill that the market undervalues. Which raises a final troubling thought on situational hitting: What if thinking about situational hitting as a skill is the wrong paradigm? What if it’s an attitude? What if it’s less the ability to alter your swing and more the ability to decide to alter your swing. Could Trent Grisham have stopped swinging from his heels with two strikes and focused on putting the bat on the ball? Only Trent Grisham knows for sure, but the ability to make that choice might be a skill in and of itself, one that’s propped up by a culture that values, and demands situational awareness.

You optimize around what you measure. It’s not intentional but it is inevitable. Presently, hitters are rewarded for what’s measured: OPS. They’re punished for anything that drops that OPS, even when that thing happens to be situational hitting that could increase the team’s win probability. From the team’s perspective, that’s a bad situation, but it creates an opportunity to find untapped value. And the key here is absolutely changing the team culture.

Changing culture? Or just changing lineups?

Another way to get the most from what you have is to make sure you’re deploying your resources efficiently. The first step to doing that is to accurately – you could say “meritocratically” – assess your players. Xander Bogaerts is now the team’s second baseman. Ha-Seong Kim, the team’s best infield defender, will take over at shortstop. This is the proper alignment of talent. Kim has more range, a stronger arm, and will provide peak value to the team playing at shortstop. If you’re looking for a clear sign that a culture is shifting towards a focus on elevating winning above the self-interests of players, this is what it would look like. That doesn’t mean that’s what’s happening. This is just one data point – it could be an anomaly, not a trend. This is also what every feud between a star player and management that wants him to play a different style than he prefers looks like in the beginning – hopefully not, but you never know. And we’ll find out through the course of the season whether a culture change has occurred, or the team is just rearranging the deck chairs.

This offseason manager Mike Shildt also stressed the importance of a dynamic approach to offense, placing great emphasis on productive at bats and situational awareness. This is not too much to ask of extremely talented players on long term guaranteed contracts. These players should be less worried about their OPS and more worried about their contribution to winning the game at hand. Shildt is saying exactly what you’d hope to hear from a manager bent on changing culture. It takes a lot more than just sound bytes to change culture. The tall task before Shildt will be introducing accountability and cultivating buy in. Time will tell if his statements were the wind of change or just hollow words spoken into to the void.

Culture is notoriously difficult to measure - and almost impossible to measure by those outside the organization. But people inside the organization can do it. Members of an organization often develop an intuitive feel for culture that’s accurate and, in some cases, self-defining. And sometimes, culture can be measured. For example: How often did the brass want Hader to come in and he refused? Were there instances in which they expected Grisham to stop swinging for the fences, but he didn’t? Was there any pressure to optimize the defensive lineup during the 2023 season? We on the outside will probably never know the answers to these questions, but people inside the organization know. Of course, that doesn’t mean that outsiders have no methods for assessing culture.

In God we trust. All others must bring data.

How much win probability is culture worth? Measuring a qualitative thing like culture isn’t the same as measuring, say, OPS. And we tend to discount phenomenon we can’t measure. But while we can’t calculate exactly how much win probability culture is worth, we can calculate how much value-added from culture change was needed to make a difference to the ’23 Padres: 1.2 percent. The 2023 Padres needed two more wins to make the playoffs; two wins out of 162 games is 1.2 percent. If a better culture would have provided that 1.2 percent boost, then it’s fair to say that the ’23 Padres’ downfall was partly due to culture. Looking at 2024, we don’t need a precise number to know that a team that lacks the type of talent that the Dodgers have collected can’t afford to ignore any advantage that might contribute to winning. Whatever value a better culture might add, the ’24 Padres can’t afford to ignore it. And perhaps for that reason, they won’t.

There are future implications to consider as well. The team is staring down a decade in the bitter cold slowly pressed flat under the weight of massive contracts tied to depreciating assets, that is, if they cannot figure out how to transform talent into winning. It’s time to shed the vices of Padresing. They need to find a way to counteract that effect. Culture is a great place to start. Everyone pulling in the right direction. Towards the True North. Towards winning it all.

Go Padres.