The Padres continue to win close games despite one of the worst offensive stretches in the team’s recent history. And it’s interesting to think about the ways a struggling offense affects the machinery of a team as a whole. When games are very close this increases the pressure to pull starters who get into trouble the third time through the order. Early starter exits in close games increase the usage of the team’s high leverage relievers. Increased usage leads to fatigue and injury risk, and increases the available game film of the team’s relievers to the rest of the league. Tight games prevent the team from being able to slot in players they may want to get a look at but don’t want to risk playing in crucial game situations (Luis Campusano has had 19 plate appearances since his call up May 2nd). This of course means more of the incumbent wear and tear of the grueling 162 game schedule accrues to the team’s starters. The cumulative downstream effects as the season winds on are hard to quantify, but should be considered part of the cost of inaction in addressing structural shortcomings of the team’s roster construction.

The team’s offensive woes can be split into two simple categories:

Terrible slumps from important stars: Fernando Tatis Jr, Luis Arraez, and Jackson Merrill1

Profound absence of production from left field, catcher, and off the bench

Only one of these two problems can be fixed deterministically. And there will be plenty of talk about trades to address the structural weakness of the roster in the coming weeks.

It’s a lot more difficult to snap a player out of a slump. But it helps to try to understand why a player might be slumping.

When we wrote about Tatis’ slump we noted that all slumps are multifactorial, but given the magnitude of Tatis’ slump, the worst of his career, it seemed relevant that his slump started right around the time he suffered a hit-by-pitch that initially looked like his season might be in question. Our conclusion was that even if an injury sustained in the hit-by-pitch were a big factor in his slump, it was a soft tissue injury that is likely to resolve eventually, and hence it seems more likely than not that Tatis will eventually return to better form.

Jackson Merrill’s slump is even harder to prognosticate. Merrill’s slump seemed to start after he missed the final game in Colorado May 11th with a mysterious illness. He has not been right since:

Most alarming has been his strikeout rate. As a rookie Merrill’s strikeout rate was only 17%. The jump to 27.5% during the slump has been accompanied by a drop in average exit velocity from 92.2 MPH pre-slump to 85.3 MPH, and a drop in hard hit rate from 51.1% pre-slump to 27.5%. During that span more than a third (33) of his plate appearances have come against lefties. But he hasn’t looked good against right-handers either. The past month has been the first sustained slump of Merrill’s career. And it’s difficult to pin down specific causes. It’s hard to imagine that the blisters he was dealing with explain such a dramatic decrease in performance metrics. Merrill is no longer a precocious rookie. He’s been recognized league wide as a dangerous hitter and teams are game planning for him. Slumps are an inevitable part of baseball, and in the absence of any identifiable long term concern, it seems likely that this is a garden variety slump. The type that all players eventually go through. As with Tatis, it seems more likely than not that Merrill will return to form eventually.

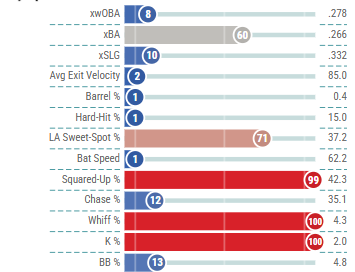

But unlike the other two, Luis Arraez’ struggles have come with some troubling findings. Arraez is having the worst year of his career statistically:

Batting average notoriously can be subject to luck year to year. But deterioration in some specific underlying metrics suggest it’s more than just bad BABIP luck.

We wrote about the elements that made Arraez an effective hitter when he joined the team last year. It’s not just his contact ability, though that is a part of it, and he remains miles ahead of the next closest hitter in this regard:

What made Arraez a unicorn hitter was the emergent properties of an unheard of consistency across multiple aspects of hitting:

He consistently has the lowest whiff rates in the MLB;

While his exit velocities are rarely >95 MPH, he’s at the top of the league in average exit velocity on non-hard hit balls ranking 2nd, 1st, and 2nd the three seasons prior to joining the Padres (typically around 85 MPH);

His exit velocity standard deviation was the lowest in baseball the three seasons prior to joining the Padres - meaning there’s a much narrower distribution of his exit velocities than most players;

His launch angle standard deviation was among the lowest in the league - meaning the balls he puts in play are within a narrower launch angle range;

He was among the very best in the MLB at hitting the ball into the launch angle sweet-spot, meaning a launch angle of 8 to 32 degrees, which are the most productive ranges for hitters.

To summarize these tendencies: Arraez had the ability to constantly hit high quality, medium exit velocity line drives within a narrow launch angle window that leads to lots of hits falling.

In the Statcast era balls hit into the launch angle sweet-spot with an exit velocity below 84 MPH still have a cumulative batting average of 0.541. Hard hit balls in the launch angle sweet-spot carry a batting average of .687. Here are an array of medium exit velocity hits through the launch angle (LA) spectrum:

You can see why in certain launch angle ranges even soft contact is likely to be a hit. And those are the precise launch angles that Arraez was better at finding than anyone. This, not luck, was the secret to his ability to maintain very high batting average. He demonstrated quantifiably sublime bat control across an enormous sample size prior to joining the Padres.

Since the elements above are what made Arraez a special hitter, his performance in these areas is a natural place to search for an explanation for why Arraez has been so much less effective this season. And when you drill down, you see that something has changed.

While Arraez continues to have the best contact rates in baseball in 2025, the underlying indicators of the quality of that contact have dropped dramatically. Starting with the average exit velocity on non-hard-hit balls:

Where he was once elite, he’s become middling. This has followed a decrease in overall exit velocity, and an increase in launch angle and launch angle standard deviation since joining the Padres:

And perhaps most significant, his ability to hit the ball into the launch angle sweet-spot has cratered:

The confluence of sizeable drops in overall exit velocity, exit velocity on non-hard hit balls, and launch angle sweet spot percentage, combined with a steeper launch angle and larger launch angle standard deviation imply that Arraez’ bat control has degenerated. And without sublime bat control, Arraez’ ability to be a consistently productive hitter has eroded. It’s not BABIP luck, it’s that the balls in play are of demonstrably worse quality in 2025 than in years prior.

But why?

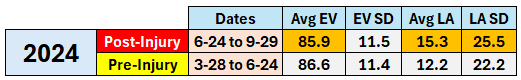

There might be an answer when you dive into his 2024 season. Arraez got off to a great start when he first joined the Padres in 2024, but on June 25th he suffered a bad injury tearing the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of the left thumb:

Image Courtesy: TheInjurySource.com

The thumb UCL stabilizes the pinch grip between the thumb and index finger. It’s almost inconceivable that a player could suffer this type of injury and not have a weakened bat grip as a result.

But is there any evidence that this may have affected Arraez’ performance?

Perhaps. Look at the difference in average exit velocity, average launch angle, and launch angle standard deviation pre and post thumb UCL tear:

His average exit velocity dropped after the injury, and his average launch angle and launch angle standard deviation rose to levels higher than at any point in his career. Random luck can be the reason for any outcome in life. But the quantifiable difference in specific indicators of bat control before and after the tear to a stabilizing ligament is remarkable. This is the exact picture of what deterioration of bat control would look like. For a player that just turned 28, it’s unlikely that such deterioration is due to aging out.

Arraez was clear that he played through a lot of pain in the second half of last season, and knew he would eventually need surgery:

He completed the surgery in October and the presumption was that the surgery put the injury behind him. And maybe that’s true.

But it’s again remarkable that in the first season after undergoing a significant surgery to the hand that generates and directs much of the power in a swing he has seen a big drop-off in exit velocity, a career worst in fact. And it raises the question of whether there is any lingering effect from this injury and surgery. A compromised UCL reduces the ability to clamp down and maintain barrel control through impact. Would surgery 100% correct all instability or pain issues? With pain or instability in the thumb, a hitter is likely to make off-center contact, and have difficulty keeping the bat head from getting knocked off plane on contact. We can’t help but call back to this at-bat from last month:

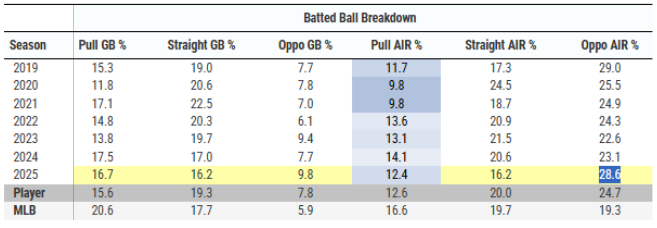

There’s something not right there. That’s a serious wince. But more importantly, his barrel control is really bad, especially after contacting the ball. The barrel is actually deflected downward and the ball is popped up (thankfully foul, but still). This is the specific type of really bad contact that Arraez has been experiencing all season; he’s been lofting opposite field fly balls at an alarming 28.6% rate this season, more than in any prior season since his rookie year, and drastically more than the MLB average of 19.3%:

These are not productive hits for Arraez. He’s hitting .111 on opposite field fly balls in 2025, with an average launch angle of 35 degrees and exit velocity of 83.2 MPH. From 2021 to 2023 his average exit velocity on hits of this type was 87.2 MPH.

A look at Arraez’ swing efficiency from 2023 until the thumb injury in 2024, and the difference in efficiency since is also sobering. Prior to his injury Arraez was reaching an ideal attack angle 47.9% of the time. After the injury this dropped to 42.5% and has only recovered to 43.3% in 2025.

Playing in Petco Park also takes away some hits for Arraez, as it does for almost every hitter. The relatively short dimensions in Petco mean the outfielders play closer to home plate than in other venues. When Arraez is up in Petco the left fielder starts an average of 274 feet from home plate, while the average starting distance in all other venues is 280 feet. That means six feet less real estate to lob hits into. But this finding only affects outcomes, it does not explain the dramatic difference in the underlying process behind Arraez’ struggles.

There’s one final thing that might suggest Arraez himself thinks there’s a problem with his swing: He’s bunting more than he ever has. From 2019 through 2024 Arraez laid down a total of 7 bunts. In 2025 he’s already bunted 7 times. It makes sense once in awhile for a strikeout machine like Martin Maldonado to lay down a bunt, because Maldonado struggles to make contact, and there are specific situations in which contact is rewarded more heavily than usual. But a contact hitter with a strikeout rate of only 2% should not be bunting frequently because he does not struggle to make contact. But perhaps Arraez is struggling with confidence in his usual ability to produce line drives.

Those decrying that Luis Arraez has always been the hitter he’s turned into in 2025 are wrong, and easily proven so. This is the worst he’s ever been as a professional. Not just by box score outcomes. The physics of the balls he’s put into play are much different than earlier in his career. Unfortunately a look under the hood suggests it might not be just bad luck. But the season is only a little more than a third of the way through, which is still a small sample. So it’s impossible to rule out bad luck entirely.

One way to get a better idea would be to adopt a convention from the NBA and use tracking data during batting practice to analyze a player’s physical performance. Nearly every NBA team now tracks their players’ performance during shooting practice and uses this information to iron out mechanical problems that lead to slumps, and recognize when disappointing game outcomes are just bad luck for a shooter that is in good form, and pre-empt unnecessary mechanical changes that may prove maladaptive. Is Arraez consistently getting good exit velocities and launch angles during batting practice? If so then perhaps his dismal on field performance is just small sample size theater, and he’s destined to return to form. We can’t know these things. We can only hope. But the team could certainly study this.

If any of Arraez, Tatis, or Merrill are in for prolonged slumps, that puts increased leverage on pursuing a structural improvement of the other parts of the roster that are helping to manifest a very bad offense. It’s nearly certain that the team brass is awaiting further news on Michael King and Yu Darvish to inform decisions on how much future value to trade for present value. And that’s sensible. But it’s wise to keep track of the opportunity cost of delay as well.

We don’t think Bogaerts is in a slump. We think this is who he is now. We would love to be wrong.

I suspect that the real driver of Arreaz's poor performance is that his plan at the plate is to not strike out (a defensive approach), rather than a more offensive approach of trying to hit line drives. Or maybe (kinda like Xander) this is just who he is now.