This might be the best bat flip and play by play combination ever recorded:

From the incomparable @DonOrsillo

Friday felt like a reawakening. But as much as we’d like to linger in the moment, there’s a longer trend that the Padres are trying to emerge from. It’s uncomfortable, but we’re going to talk about what the Padres are trying to leave behind.

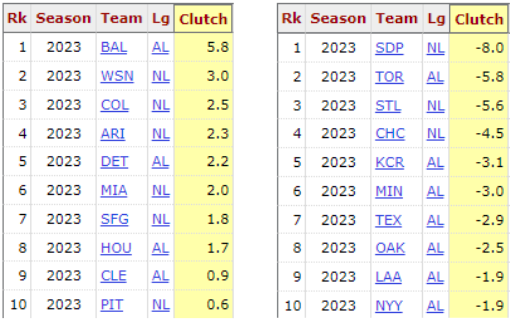

Through Tuesday, no team in baseball history had gotten the big hit less often than the 2023 Padres. The 2023 Padres had the lowest batting average in high leverage at bats in the history of the sport. Of course, the season isn’t over. They may not end the season as the worst clutch team of all time. Friday might have been the start of that. We can hope.

The received wisdom about clutch performance is that it’s entirely luck. And if that’s the case, Padres fans can breathe a sigh of relief. Nothing needs to be changed, the luck will just normalize as time goes by. But what if it’s not just luck? What if there is a process within the organization that makes the team more susceptible to bad outcomes when it matters most? How important would that be to investigate?

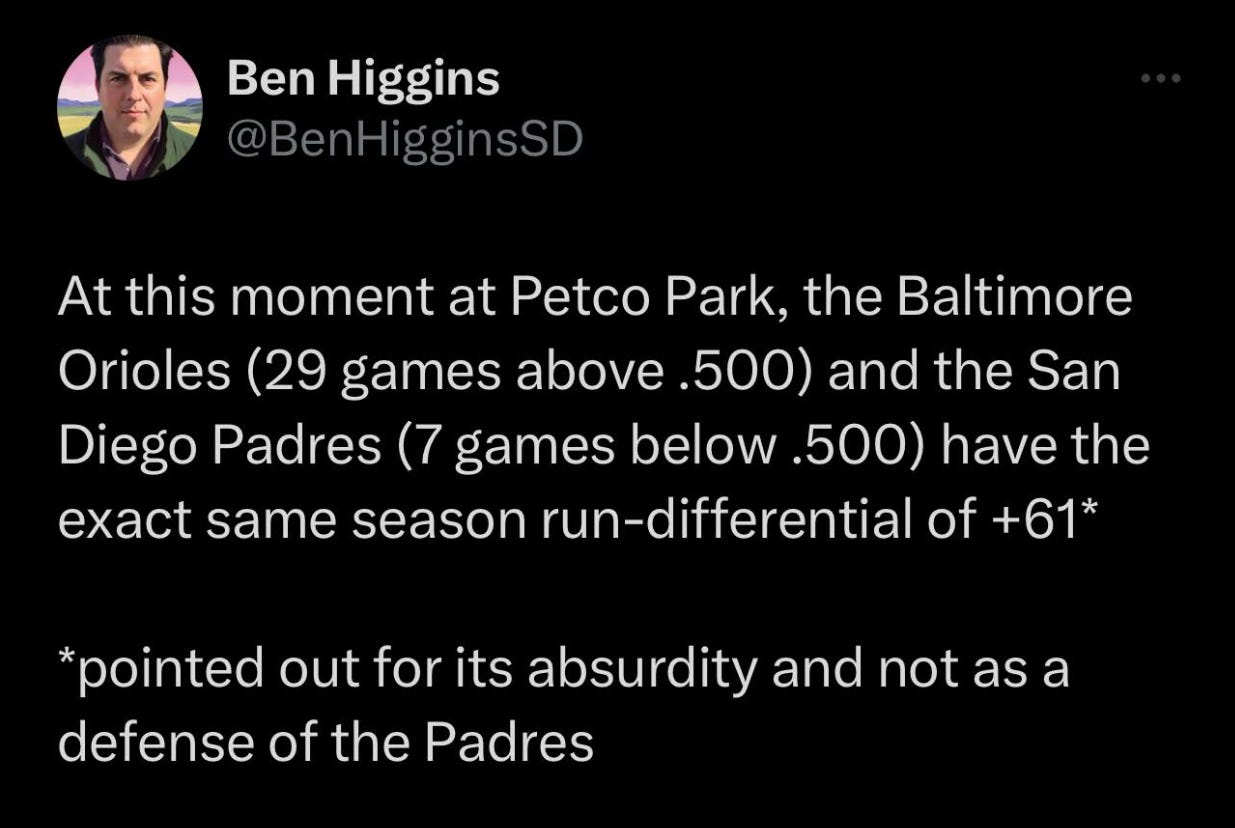

To answer that question, first we’d need to get a sense of how important it is to perform in the clutch. And the short answer is: It’s very important. Consider: At one point during Tuesday’s game against the Orioles, this was true:

Incredible. The first place, best-in-the-AL Orioles had the same run differential as the fourth-place, resoundingly disappointing Padres. We could cite other stats to make the point that converting runs into wins – and not just scoring runs – is important, but after that stat, do we have to?

So, the difference in the Padres’ and Orioles’ run differential is about zero. But the difference between the Padres and Orioles in the win column was 36 games. How? Clutch hitting. Gaze at Baseball Reference’s clutch hitting1 stats if you dare:

Even if we believe that clutch hitting is just luck, we shouldn’t believe that clutch hitting doesn’t matter. It clearly matters a lot. Of course, if clutch hitting is entirely luck, then, sure, it matters, but there’s not much a team can do about their performance. But what if it’s not entirely luck?

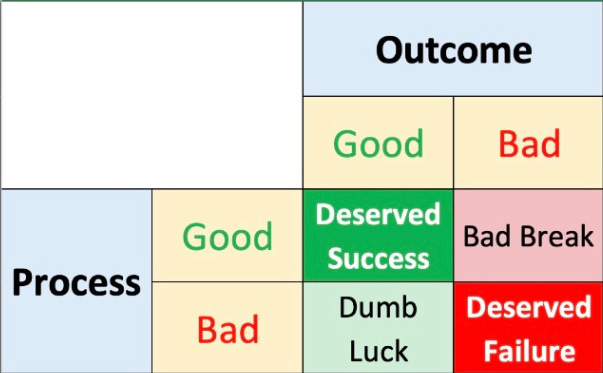

To believe that clutch hitting is not entirely luck is not to believe that there’s no luck involved. There’s clearly some luck. Of course, there’s some luck involved in basically every outcome imaginable. We might think of outcomes like this:

The Padres are clearly on the right side of that chart. But do they belong in the “bad break” square or the “deserved failure” square?

We noted before that the Padres teams from 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2023 are all among the 300 worst teams hitting in high leverage in MLB history. That is a staggering trend. Still, that doesn’t necessarily mean that an organizational approach is to blame. Luck can explain any outcome. But determining whether the Padres’ eye-popping numbers are signal or noise is important, because it will affect future decisions.

Some of what’s behind the numbers is unknowable to people outside the organization. Only the players, coaches, and executives know what conversations have been had that might influence the Padres’ approach at the plate. The best outsiders can do is to outline a framework for how the “do the Padres have an organization-wide approach problem?” question could be investigated. So, that’s what we’re doing: Not trying to answer the question (because we can’t), but determine how the question might be answered. Let’s dive in.

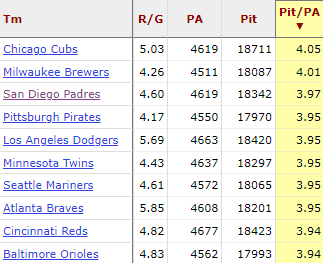

When an organization produces an extreme result, the first place to look is at any part of the process that the organization takes to an extreme. And the Padres’ process is extreme in at least one way: They take a ton of pitches. In fact, they take the third most pitches per at bat in the league:

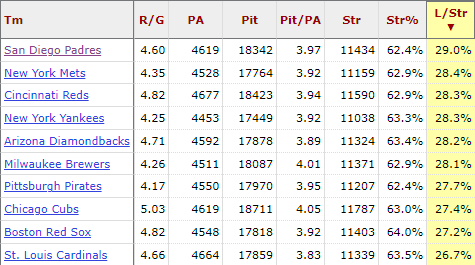

Also, the Padres are not just taking balls; they lead the league in taking strikes looking:

The Padres are also not just taking strikes on the edge of the plate; when it comes to meatballs, the Padres are vegetarians. They have the second lowest swing percentage on meatballs (yes, that’s a stat you can track) in major league baseball at 74.0%. League average is 76.5%.

That means that this season, Padres hitters have decided not to swing at 35 meatballs that a league average team would have swung at. That might not sound like a lot, but professional hitters can do a lot of damage swinging at 35 perfect pitches to hit. Someone out there might have a theory about why it’s a good idea to not swing at meatballs, but our instinct is to say that it’s good to hack at fat pitches.

The fact that the Padres also take a lot of pitches probably also explains why, though they strike out at an about-league-average rate, they’re near the top in strikeout looking percentage:

This is a multi-year trend; the Padres led the league in strikeout looking percentage in 2022. In 2021, they were in a dead heat with Houston for the league lead. In 2020 they were third in the league. In 2019 they were sixth, separated from the league lead by 0.6%. They were near league average in 2018, but third overall in 2017. They were in the top half of the league in 2016 and 2015. That is a long span of time in which the Padres were at or near the top of the league in strikeouts looking. That’s the pattern you’d expect to be related to an approach to hitting that the organization is emphasizing.

But it’s fair to ask: So what? So the Padres strike out looking more than most teams. A strikeout is a strikeout, right? Well, not exactly. A swinging strike is a relatively unambiguous event – the batter swung, he produced nothing but a gust of wind, the end. But a strikeout looking opens up a new possibility for variance: umpiring.

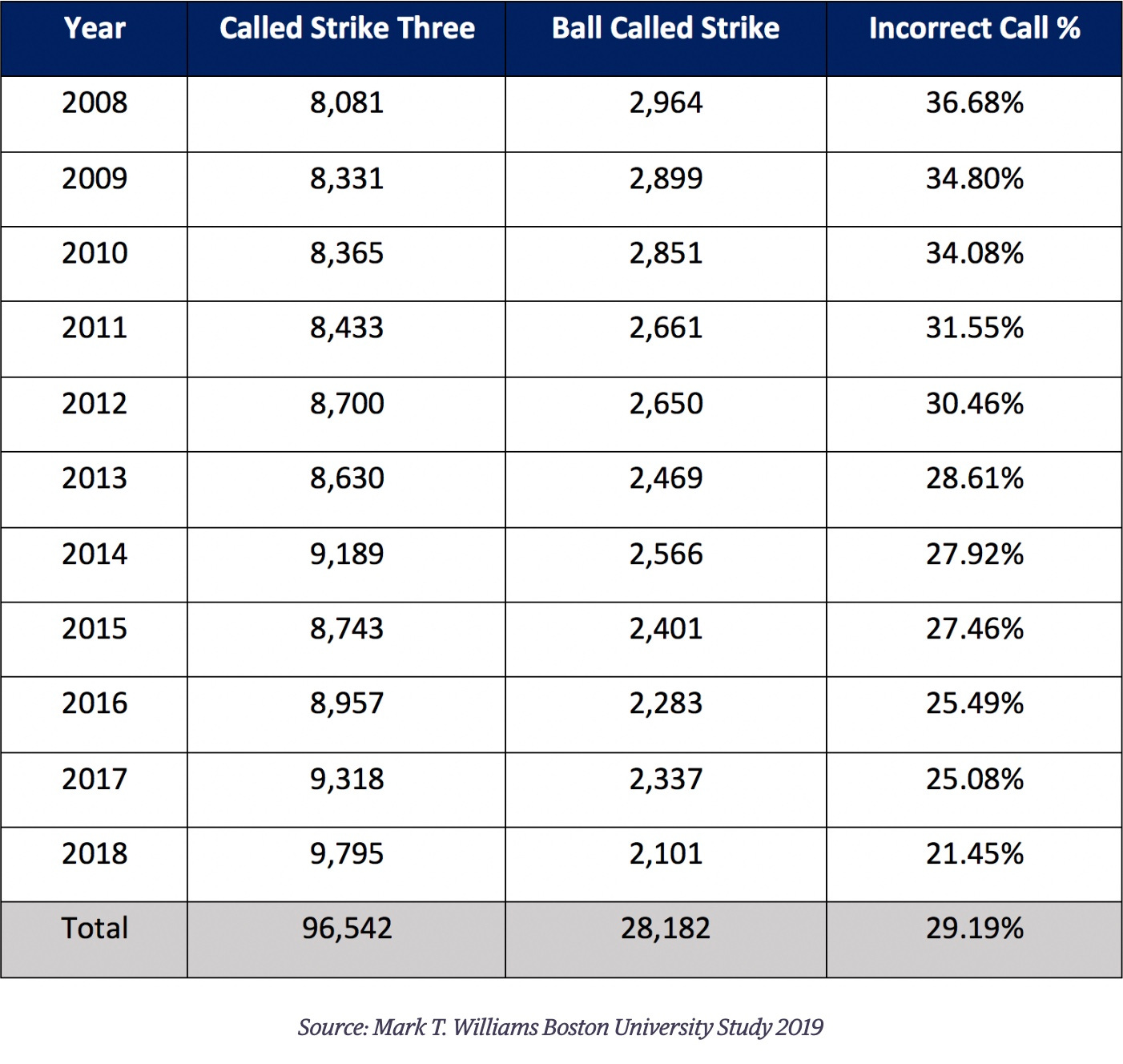

It turns out that, on the whole, umpires get a lot of calls right, and they’ve been improving through the years. But there’s a big exception, and it’s much worse than you would think: Umpires are surprisingly bad at calling strike three:

Umpires have an abominable record when it comes to making bad calls in two strike counts; even after a decade of improvement, they still call a ball a strike more than 20 percent of the time. During the 2018 season, umpires were three times more likely to incorrectly send a batter back to the dugout than to miss a ball-four walk call. They unjustly sent a batter back to the dugout more than two thousand times. And that was by far the best year we have on record!

If the Padres are taking a hyper-patient approach in clutch situations – and the evidence suggests that they are – then two things are likely to be happening that would affect their clutch hitting numbers. First, they’re taking good pitches in situations where hits are more rewarded than walks. Second, they’re giving umpires more opportunities to make bad calls, and they’re doing this in situations where strikeouts are punished more than in normal situations.

Adding to the evidence that this is a problem: Pitchers change their pitch selection depending on game situation. With runners on base they throw fewer pitches in the zone. If pitchers are nibbling around the edges more in high-leverage situations, then there are probably more opportunities for bad third-strike calls. And the 2023 Padres do strike out more than normal in high-leverage situations: Through Tuesday they’d struck out in 29.33% of high-leverage at-bats (200 K’s in 682 ABs), compared to 24.83% of all at-bats. In fact, the Padres strikeout rate in high-leverage at-bats has been higher than their normal rate in each of the past six seasons, and eight of the last nine. Are those excess strikeouts what is depressing their batting average in high leverage situations?

Case closed? Definitely not. This is just pulling on a single thread. But it demonstrates an approach to analyzing the issue. An organization with the resources that the Padres have should be able to comb through the entire probability tree fairly quickly. And maybe they’ve already done this; maybe they crunched all the numbers, chased down every lead, and arrived at the conclusion that they’re mired in an otherworldly streak of bad luck. If that’s true, then it means the answer to the question “what the hell are they doing wrong?” is nothing. It means that the fatal flaw in their season is simply that the Padres are humans and sometimes humans get hit with terrible luck.

We hope that everything about the Padres clutch woes is just simple, unbelievably improbable, sustained bad luck2. Because if that’s true, then things will eventually even out. And maybe it is true – after all, improbable things happen in baseball all the time. Right, Fernando?

The Padres aren’t dead yet. Friday felt like a reawakening. There is a 39 game gauntlet left to run, and if the Padres can perform 5 games better than their wild card opponents down that stretch, they’ll have survived. We simply can’t know yet if the struggles this season have all been bad luck that is behind us, or if there is a process at work, and more struggle yet to come. Honestly, even if there is an identifiable flawed process in place, with 39 games to go, it’s hard to imagine that would be enough time to implement change. The die is cast.

We want to believe that this team isn’t fatally flawed. Yet proof in either direction is elusive. When you believe something in the absence of proof, that’s called faith. So here’s what we’re going to do: We’re going to keep searching for answers, but until we find them, we’re going to do the only thing we can do. Keep the faith.

Clutch is calculated by evaluating a hitter's win probability contributions (WPA) against the average leverage he's faced (aLI) and subtracting his hypothetical context-neutral contributions (WPA/LI). The formula is (WPA/aLI) - (WPA/LI) It’s just a way to see how a player has added to the win probability of his team in different situations. It doesn’t tell you why, i.e. it doesn’t tell you if it’s just luck.

That wouldn’t actually be that surprising for San Diego fans.