The Padres have crossed the Rubicon; their failures have passed a threshold where no matter how the season turns out, a reckoning is coming. Even a miraculous run to the postseason won’t silence the calls for change after what has been the most disappointing season in recent memory. Change is coming. But what change? As important as it is for something to change, it’s at least as important for the right thing to change.

So, let’s examine the team.

Here is the Padres season summary going into Monday:

Here’s what jumps out as notable: The Padres have a much worse record (56-62) than their run differential (+57) would suggest. This is explained by their horrifying 6-19 record in one-run games, and their nearly-record-setting 0-10 record in extra innings. The Padres do not come through when it matters. This is the fatal flaw of the 2023 Padres, but its scope, until now, hasn’t been fully understood in the context of baseball. And if you’re not yet convinced, let’s dive into how historically futile this team has been in big situations. Because even though we’ve been talking about this all year, we have somehow not reached the bottom of it.

By one measure, the Padres’ offense is exactly average. Entering Monday, the average MLB offense scores 4.58 runs per game. The Padres score exactly 4.58 runs per game – in that sense, they’re the definition of average. A baseball executive seeking to save their job might argue that a league-average offense should be good enough, and might point out that multiple World Series winners the past 25 years had a league-average offense or worse. From this perspective: Why all the negativity? We’re average.

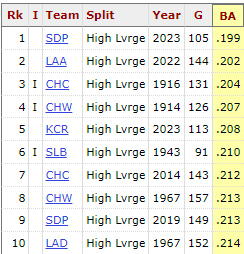

The problem is that this team has been shockingly bad at converting runs into wins. If there’s a single observation that captures that, it's that they never seem to be able to get the big hit in close games. As we’ve discussed more than once, this team’s struggles in the clutch are the stuff of legend. Early in the season, the Padres were literally the worst-hitting team with runners in scoring position that the world has ever known, though they have heated up and merely become one of the worst-hitting teams with runners in scoring position since the dawn of time. But they’re still very bad when it matters. Baseball Reference’s high-leverage batting splits deem the Padres the worst in the majors at hitting in big situations this year:

The sample size is 786 plate appearances, that’s not small. Also, that stat isn’t “bad compared to how they normally hit” – it’s just “bad…period.” The only team that is almost as bad as the Padres in high-leverage situations is Kansas City, but Kansas City is just a bad-hitting team: They’re 28th in the majors by Fangraphs WRC+ (the Padres are tenth). For the kinda-good-hitting Padres to be below the definitely-bad-hitting Royals (not to mention the White Sox and Rockies) just demonstrates the enormous gap between “normal Padres” and “crunch-time Padres”. And it (somehow) gets worse: The Padres aren’t just the worst in the league hitting in high leverage this season – they’re the worst all time:

There has never been a team, in baseball history, that has gotten the big hit less often than the 2023 San Diego Padres. The 2023 Padres are the worst hitting team in high leverage since the Bronze Age (and possibly longer…Stone Age baseball records leave much to be desired). But it’s not like this year came out of the clear blue sky. There are about 3,000 individual team seasons of baseball in the Baseball Reference database. Of the 300 worst hitting teams in high-leverage situations, SEVEN of them are recent Padres teams! The 2015, ’16, ’17, ’18, ’19, ’21, and ’23 teams are all on the list1. The 2020 Slam Diego team and last year’s playoff team are the only recent teams to not be in the top ten percent of the most futile high-leverage hitting teams of all time2. These are dismal results – seven of our last nine teams are in the top ten percent, while no other organization has more than four. With those numbers, “what the hell are they doing wrong?” isn’t just a valid line of inquiry – it’s a necessary one.

As bad as that performance in high leverage looks, it’s nothing compared to the team’s failure in extra innings. Across 55 plate appearances in the Padres’ extra-innings games this year – in which they’ve gone 0-10 – here are their cumulative statistics:

15 major league teams have played at least ten extra-innings games this year. Would you be shocked to learn that the Padres have the lowest batting average of all of those teams?

You can probably guess what’s coming next. Here is where the 2023 Padres batting average in extra innings stacks up against all teams with at least 10 extra-inning games played since the free runner on second was introduced in 2020:

The 2023 Padres are the worst hitting team in extra innings since the advent of the modern rules.

But hitting isn’t the only source of the Padres’ extra-innings futility; bonus frames have been a nightmare for the bullpen:

That ERA – which is very bad – is actually a bit worse than it seems. Because remember: If the free runner on second scores, it’s not counted as an earned run. So more than 8.44 runs every nine innings have been crossing the plate against the Padres in extra-innings games. Since each extra frame starts with a runner on second, some scoring is inevitable. It turns out that the expected runs scored with a runner on second base and no outs is 1.18. But the Padres have allowed 23 runs in 10.2 innings pitched in extra innings this season. That’s 2.16 runs per inning, an “ERA” (scare quotes because of the free runner) of 19.44!.

And – stop me if you’ve heard this one – that 2.16 runs per extra inning is historically bad. Since 2020, 72 teams have played at least ten extra-inning games in a season. The Padres 2.16 runs per inning is the worst among those teams, and it’s not particularly close:

The 2023 Padres have a credible claim to being the worst clutch team in history. At this point in the season, losing close games feels normal. But we should remember: This isn’t normal. This is ineptitude on a historic scale. We should not think “that’s baseball,” because this is not baseball – not normal baseball, at least. Even as we’ve drawn attention to the clutch woes across the year, thinking we’ve identified the nadir, it’s always a false bottom. There is a problem here, and the Padres should try to fix that problem.

Why do recent Padres teams and especially the ’23 team struggle so badly in the clutch? A likely culprit is the organization’s approach to hitting, i.e. the “three true outcomes” approach, which we’ve written about before. To sum up that argument: “Three true outcomes” is a great approach for maximizing runs, generally, but a suboptimal approach in situations when one or two runs will probably win a game. It’s worth wondering: Is an overcommitment to that approach causing the Padres’ struggles in the clutch?

Allow us to speculate on that for a moment. Moneyball – the most influential baseball book of the past several decades – is decidedly against the notion that some players are “clutch”. Oakland A’s GM Billy Beane – the book’s protagonist – was a vocal non-believer. From the book:

Of the many false beliefs peddled by the TV announcers, this fealty to “clutch hitting” was maybe the most maddening to Billy Beane. “It’s fucking luck,” he says

Beane was railing against what he saw as a superstitious belief. This is the book that has become something akin to a bible for modern day GMs, presumably including AJ Preller.

It's possible that the Padres have over-applied beliefs about the non-existence of “clutch”. It might be true that there aren’t really “clutch” players (i.e. ice water in the veins) who perform better in high-leverage situations than they do the rest of the time. But even if we grant that, it can still be true that there are types of players who – by performing at their normal level during high-leverage situations – get better or worse results in those situations. Boiled way down: Slap hitters might be better designed for those spots than home run/strikeout kings. Are the Padres factoring these things into their player analysis? It seems like a question worth asking.

If you’ve watched the 2023 Padres, you’ve witnessed arguably the worst clutch hitting team in the history of baseball. You’ve also witnessed perhaps the worst clutch pitching team, at least in extra innings, in the history of baseball. That’s quite a combo. If being the worst-clutch-hitting team of all time is pure luck, and we have 3,000 seasons of team baseball available to analyze, then the odds of being the worst-clutch-hitting team in history – which, by some measures, the Padres are – is one in 3,000. Same for pitching: There’s a one in 3,000 chance of being the worst-clutch-pitching team, and by some measures, the ’23 Padres are that team. The odds of being both the worst clutching hitting team and the worst clutch pitching team – if those titles are purely the product of luck – is one in nine million (3,000 * 3,000)!

One more time: One in nine million! If a team becomes the worst purely because of luck. The Padres should consider that they might be more than unlucky. Because although one-in-nine-million probability events do happen (the odds of being born with the talent of Shohei Ohtani, for example, are probably about one in nine billion, but that happened), but they’re rare. The ’23 Padres are rare for all the wrong reasons. We should ask ourselves questions about why that is.

We can’t know exactly what underlies the problems with the Padres performing in the clutch. But we can know that one way to never improve a problem is to deny the problem exists. If the Padres struggles in the clutch are nothing more than luck, this is great news, because nothing needs to be fixed, this will all normalize over time and the team will be absolutely fine. We wonder if this was what the 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2021 Padres told themselves.

There has been a secular trend in baseball to deemphasize hitting for average, thus there are a fair amount of modern teams on the list of worst batting average in high leverage situations all-time, 118 of the top 300 are teams from 2003 and later. However, the Padres are still the most extreme example in all of baseball in fielding teams with poor batting averages in high leverage situations.

The 2014 and 2022 Padres are in the top 20%

Nice analysis, I didn't realize the extra inn pitching defect. Excuse me if you also touched on this but the Pads lead (led) MLB in BB and just by the eye-test, when Billy Beane asks "Do I care how they get on base", the answer should be YES !! These walks aren't scoring runs, you need hits or at least grounders to move them (non BL situations). Soto's an interesting extreme, a #3 that walks a lot - did he exacerbate our situation? Is he properly being accounted for in RISP averages ie when he had the chance did he knock in the run (or just walk). Lastly we have the best Pitching ERA in the NL, prob the best Pads season in years. Is that masking how absolutely terrible our hitting is? Why isn't anyone talking about our lights out Pitching? This has been a crazy season of absolute extremes, but maybe points out some weaknesses in analytics because this team SEEMS to be designed properly.

If you run the numbers for all 3,000 teams *through 119 games*, I'm sure you'd find some teams which were worse performing at this point in the season. (They probably end up pretty low on the list anyway, but there's a major statistical difference between being the worst through 162 and the worst through 119 with a built-in assumption that the remaining 43 games precisely extend the trend.)

The broader point about being consistently bad in these situations is a valid one, however, and player valuation may be a part. But I'd lean more towards approach, whatever that contains [ie. pitches/location to look for, general goal (contact, power, etc.), late game decisions], rather than luck or roster composition.