Margin Call Part 2

Lineup Optimization

Part 1 discussed a unique piece of the 2025 Padres identity: the willingness to accept a tradeoff of fewer total runs for a higher chance of scoring at least one run, with the sacrifice bunt. This trade makes sense when you are able to win games with fewer runs. The full strength 2025 Padres made a nearly irrefutable case they could win this way. While it’s fair to wonder if they were holding themselves back, preventing an even better version of themselves by making this trade again and again, it’s hard to imagine they could have performed significantly better than the 31-13 record they amassed in games they’ve made this trade.

But the winds have shifted. The Padres are reckoning with the loss of Jason Adam, Michael King’s purgatory, Dylan Cease’s battles with an unquiet mind, and the misadventures of Sears and Cortes. The notion that this is still a team poised to win with the exact same formula starts to falter. A diminished ability to protect small leads puts a higher premium on scoring runs. And on the offensive side, the (regular) season-ending injury to Xander Bogaerts is a brutal headwind to the team’s pursuit of run maximization. These developments are reasons to look into the marginal aspects of the game the team directly controls.

The easiest way to increase total offense is to dial back the usage of the sacrifice bunt (especially the Padres league leading tendency to give up outs early in the game). But this is a diminutive change with only 22 games remaining. The best way to score the most runs is to hit for power. For much of the season the Padres just didn’t have many hitters capable of this. But that’s changed since the trade deadline. Yet there’s a strong case to be made that the lineup has not been optimized despite having the players to do so.

Lineup Optimization

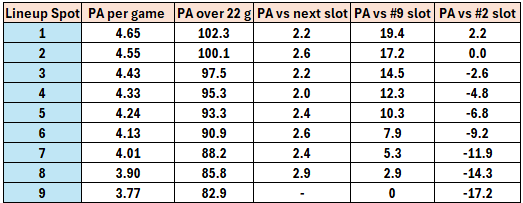

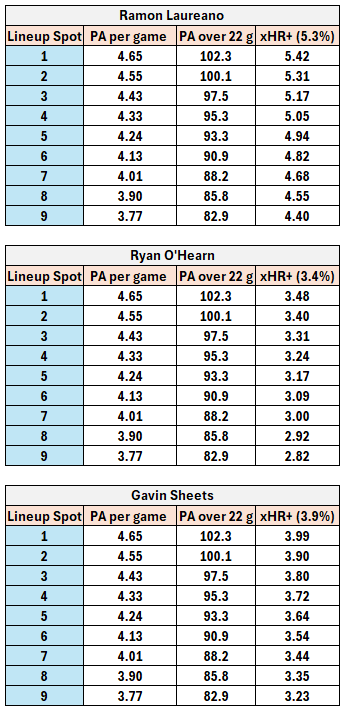

It’s helpful to look at the number of at-bats different spots in the order are expected to have across the final stretch of the season to estimate the impact that lineup optimization might have. It’s easy to map this out using the average plate appearances per game of each spot in the order:

With 22 games left, the number of plate appearances from hitting low in the order versus hitting high in the order can represent multiple games worth of at-bats for the individual hitter. A team in search of more offense needs to consider who to award those surplus at-bats to.

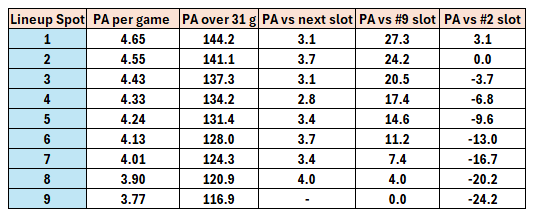

The Padres leader in home-run rate by a wide margin is Ramon Laureano with a 5.3% home run rate on the season, and 5.6% since joining the Padres. Laureano has taken 125 plate appearances across 31 games since joining the Padres. He’s batted 5th, 6th, or 7th for 26 of those 31 games:

This might not seem like much, but it’s likely he would have accrued significantly more plate appearances batting higher in the order over that span. This too, is easy to map out:

For each of the top spots in the order, Laureano would have accumulated more than two full games worth of individual at-bats across the past 31 games:

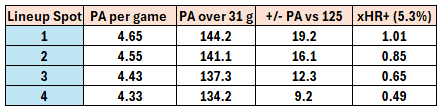

And it’s trivial to estimate the number of additional home runs expected over that span with each of the changes:

The addition of Laureano as well as slugger Ryan O’Hearn (3.4% home run rate) certainly bolstered the team’s scoring output, as they’ve averaged 4.74 runs/game since the trade deadline (the Phillies have the 10th best offense in the league with 4.75 runs/game). But it’s likely that some run scoring output was left on the table in the way that the Padres lineup has been deployed thus far.

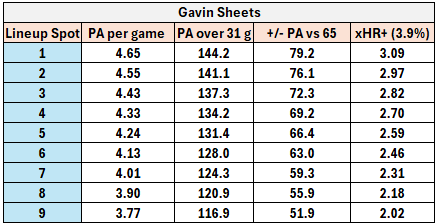

Ryan O’Hearn has started only 21 games and amassed 103 plate appearances since joining the Padres. And the arrival of Laureano and O’Hearn seemed to relegate the team’s second-most successful slugger to a part-time role. Gavin Sheets has the second highest home run rate at 3.9% on the season. Yet he’s started only 16 games since the trade deadline, with only 65 plate appearances across that span.

We can project the expected additional home runs that would have been hit over that same span had O’Hearn and Sheets started over that span in various spots in the order:

If O’Hearn and Sheets had started every game since the deadline the team would likely have ~3-4 additional home runs. That’s only a handful of total extra runs across 31 games. But the Padres lost five games by one run, and a total of nine by three runs or less across that stretch. The change is marginal, but close games are decided on the margins as a rule.

That’s in the past, but the same projection can be used for the final 22 games as a way to visualize the opportunity cost of benching any of the three across the remaining games:

There is some oversimplification here as matchups will vary night-to-night. Against certain elite left-handed starters it’s reasonable to bring one of O’Hearn or Sheets off the bench. But even accepting that, they seem to have been underutilized to this point. Again, this optimization is in the margins. The difference is likely to be only a handful of runs total across the remaining games. But it’s something the team can directly control. And every game still counts until the postseason berth is locked in.

Crowded At The Top

Part of the reason for the underutilization of the team’s power hitters is that the Padres lineup is crowded, especially at the top. Fernando Tatis Jr and Manny Machado have held the leadoff and 3rd spot in the order the vast majority of the season, and when in form provide plenty of value in these coveted spots. With Xander Bogaerts injured, there’s little argument that 4th and 5th spots should be occupied by one of Laureano, O’Hearn, or Sheets for the rest of the season. The question is how the Padres might add all three. And it’s clearly the 2nd spot in the order that the Padres should consider adjusting.

2nd Best

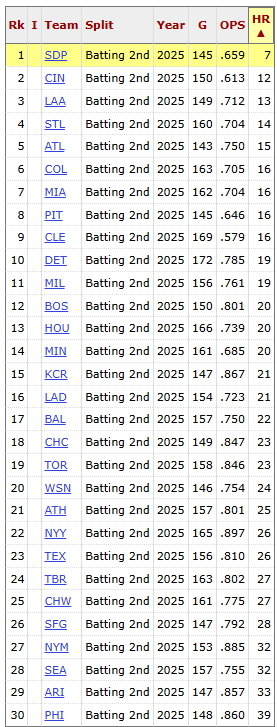

The Padres have accrued the fourth lowest OPS from the 2nd spot in all of MLB, and have by far the least home runs from the position in the league:

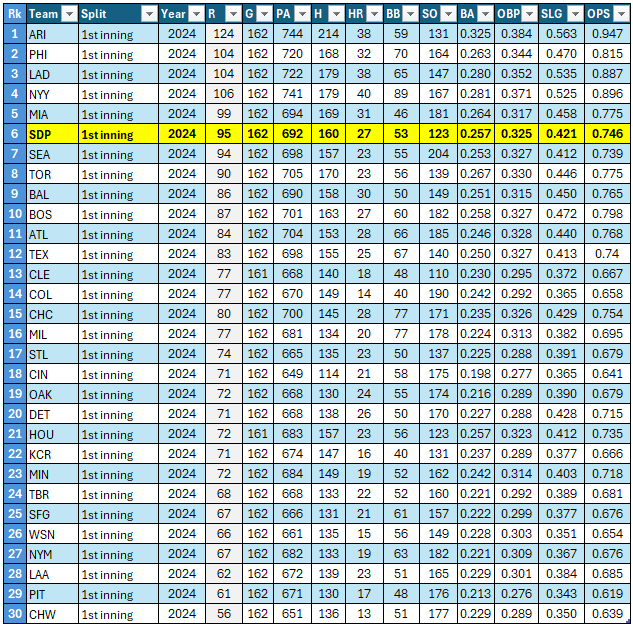

Of the 630 plate appearances from the 2nd spot, 533 have come from Luis Arraez. Some of the decision to hit Arraez 2nd night after night surely has to do with maintaining consistency and chemistry in the clubhouse. But it’s also likely that decision was made with a particular team identity in mind. One in which many early innings would start with Tatis getting on, and a hit from Arraez would set up easy RBI opportunities for the heart of the order. There was a time not long ago when this was a viable strategy. Indeed, in 2024 the Padres scored the 6th most runs in the 1st inning in all of baseball:

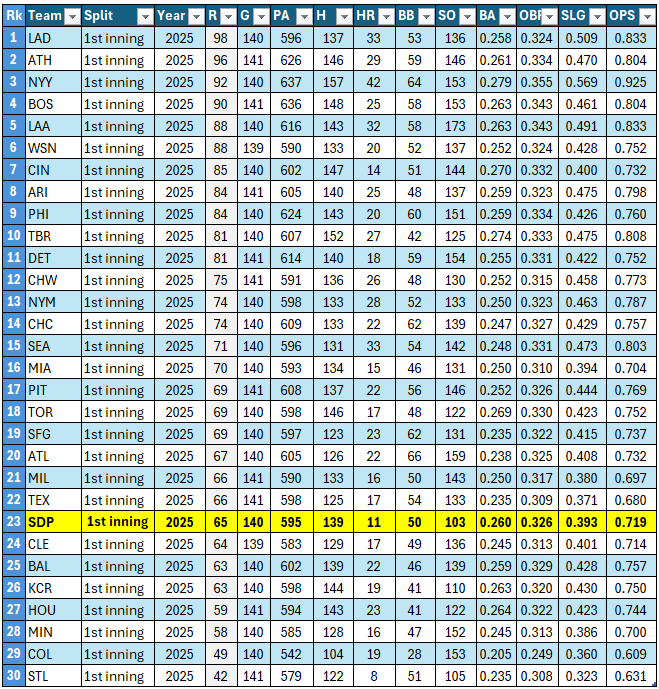

It’s been very different in 2025 with the Padres near the bottom of the league in scratching across early runs:

When the Padres acquired Arraez they got a superb hitter with every qualification to occupy a coveted spot high in the order. And in March/April/May of 2024 Arraez put up exactly the numbers the Padres had expected when they acquired him with a slash line of .342 /.380 /.413 /.793, not far off the .354/.393/.469/.861 slash line he’d put up in 2023, and right in-line with the career .327/.380/.425/.805 hitter he’d been across the first five years of his career. Awarding that hitter the surplus at-bats from hitting atop the order is a smart decision. Arraez has not been that hitter in 2025.

The prevailing theory about Arraez’s struggles is that he has entered a contact rate death spiral, expanding the zone and swinging at bad pitches. This has driven criticism of the other side of his pitch selection, the tendency to watch pitches right down the middle to start at-bats. The Statue take:

The impression one gets is that he’s leaned too far into his own hype and become a free swinger, and pitchers are baiting him to chase. The implied solution to his struggles is to be more selective, look for pitches in the heart of the zone, and lay off bad pitches to hit.

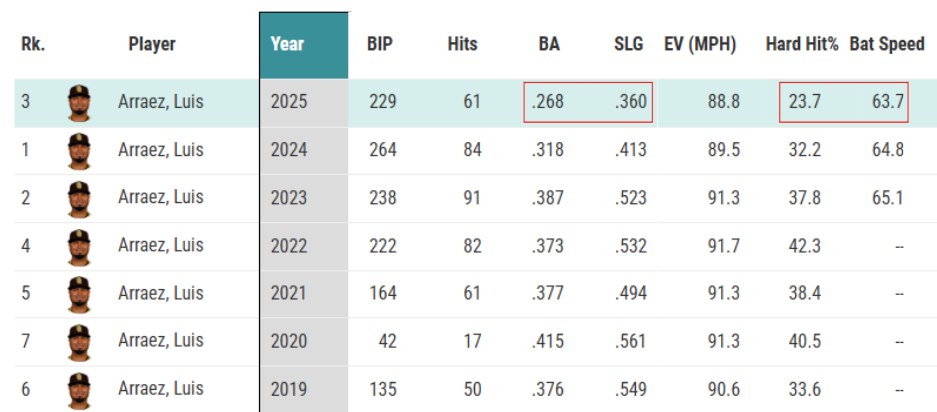

The reason this theory has not had much purchase in our mind is that this narrative simply isn’t supported by the data. Here are Arraez’s batted ball outcomes on pitches in the heart of the zone in 2025:

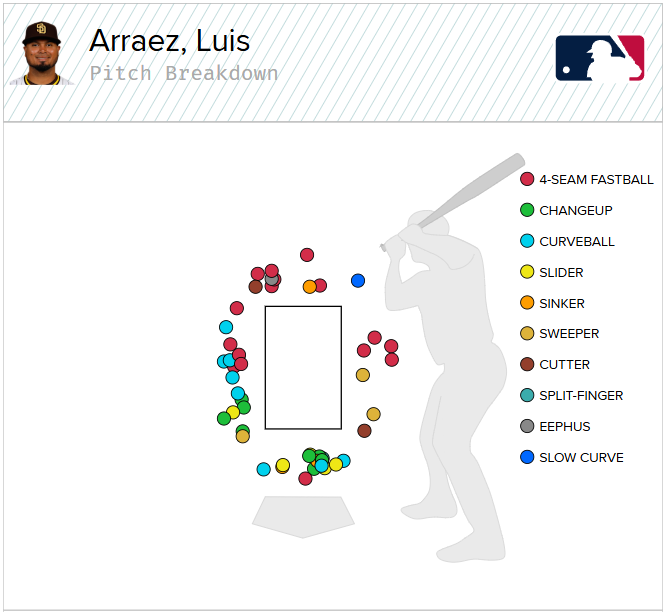

He has an OPS of .626 on pitches in the heart of the zone. And this can’t simply be chalked up to evolving defensive positioning, or playing in a suboptimal park. The bat speed has deteriorated and the hard-hit rate is drastically worse than prior seasons. Here is the location of every pitch Arraez has put into play in the heart of the zone:

These are the very best pitches to hit. The ones he’s watching on the statue takes. League-wide hitters slash .353 / .349 / .618 with a .967 OPS on pitches in the heart of the zone. He’s been right there with the rest of the league in seasons past. But in 2025 he just hasn’t been.

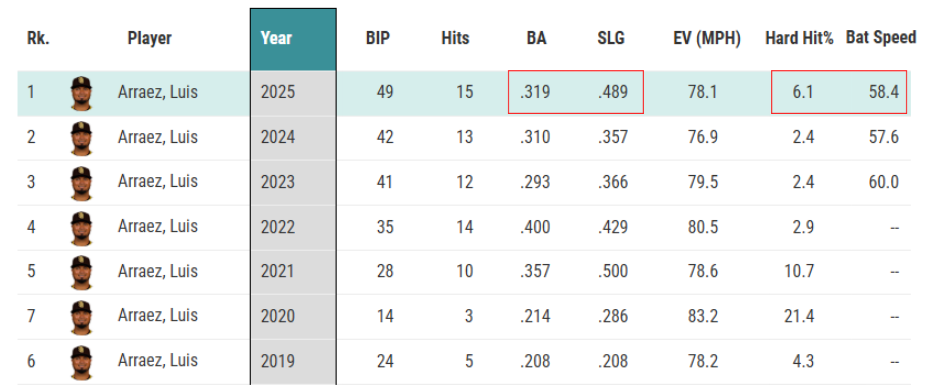

Meanwhile he’s been more productive when swinging at balls in the chase zone:

These are the pitches the league struggles to hit:

The league-wide slash line on pitches in the chase zone is .260 / .258 / .329 with a .587 OPS. It is from this observation that the theory of Arraez’s struggles was born, because that’s what normal hitters struggle with. But that is not the problem. The problem is that he cannot, to this point in a nearly completed season, get to good contact on pitches in the heart of the zone. The ones he so often watches pass by. Waxen.

We think his struggles are more fundamental than pitch selection. The skill that made Arraez a successful hitter for the first five years in the league was otherworldly bat control. Skill that went beyond what is captured in superficial statistics like contact and whiff rates. He was a hitter who could do this:

But he’s not making millimeter perfect contact when he swings any longer. Not with the same regularity that made him one of the top hitters in the game for five years.

A troubling part of this is that Arraez’s struggles do not seem to be from any visible physical limitation on the field. It’s more likely he suffered a subtle loss of fine-tuning. A deterioration in bat control so small that he’s still able to put up a career-best contact rates, but he’s off by a millimeter frequently enough that his quality of contact has cratered even when he swings at good pitches to hit.

It’s not clear that a hitter afflicted by a minute loss of precision would feel significantly different. And that’s where the coaching is supposed to support the player. Direct his attention to what he is not doing well. The things he can’t intuit himself. Findings that only emerge from external analysis.

His consistent deployment in the 2nd spot implies the team doesn’t think anything has changed. Questions about Arraez continuing to hit 2nd have been deflected with bromides about batting titles. And it’s hard to understand that.

A coaching staff is wise to support a player that is struggling, but is certain to return to form, by carrying on as if nothing has changed. Because nothing has.

But if there is something wrong, if something has changed, failing to bring it to the attention of a struggling player eventually crosses a line from vote of confidence to iatrogenic harm.

To believe that he is still the same hitter one must reconcile what the measurable difference in his batted ball profile suggests. We haven’t been able to. Previous batting titles alone are not qualifications when this type of batted ball data is available. Invoking them is credentialism.

This will sound very critical, but it’s important to keep perspective. Luis Arraez is not a bad hitter. He is having a slightly below league-average season. And there should be a spot for him in the lineup. But his struggles don’t seem destined to spontaneously resolve (we would love to be wrong). And unfortunately they don’t seem to be a matter of pitch selection alone. And for this reason the 2nd spot in the order seems to be an area that the team can elect to pursue a marginal upgrade in offensive production through lineup optimization. This doesn’t mean Arraez has to be benched. High contact rates will play well in the 6th spot when more runners on base ahead of him augment the impact of his base-hits.

Making The Pieces Fit

To keep O’Hearn, Laureano, Sheets, and Arraez all in the order at once is likely the strongest offense the team can field. This would require Arraez shifting to 2nd base, and Jake Cronenworth moving to shortstop. That is far from the optimal defensive lineup. And that’s a tough pill to swallow for a team built on the identity of run prevention. But it’s a lever the team can pull if it decides to.

When It Matters

Bad luck befell the Padres in the waning days of summer. Nothing can be done about that. But while the woes on the run prevention side may not be easily remedied, there’s still juice to squeeze on the offensive side. Lineup optimization has been deemphasized all season. It didn’t matter when the team was winning and the integrity of the run prevention strategy was intact. It might matter now.

Part 3 will press further into the margins.

Not sure what your day job is but can you just compile these letters into a folder and mail it to Tony Gwynn Dr as your resume?

Proper analysis as always, but I think we all know the changes recommended here are not coming. Sadly. Hopefully they can win even with all their self-imposed problems.