Enough of the season has elapsed that, short of a cataclysm, the Padres will be playing in October. This cast of players and their skills will be tested on the biggest stage. There are 10 games left before the second season begins. The one that truly matters. To win in October you have to have good fortune. Teams can’t control that. But they can control decisions. And a closer look at the month of September, and two innings from the past week suggests the Padres are trying to do just that.

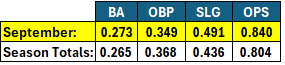

In September the Padres offense has been noticeably different than in months past. Or maybe not so noticeably since their reputation remains unchanged. But September has seen the offense more closely resemble modern offenses:

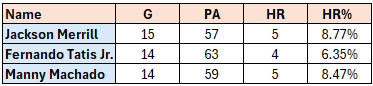

In September the team has put up its highest home run rate, strikeout rate, and slugging percentage of any month this year. It’s not a mystery why their home run production is up. Of the 21 home runs they’ve hit, 14 have come from a trio that had yet to find top form at the same time all season:

The reasons why the tentpole stars had been out of sync with one another is difficult to pin down. But it hardly matters. The Padres fortunes will depend on their stars performing when it matters most. Whether these swings carry forward:

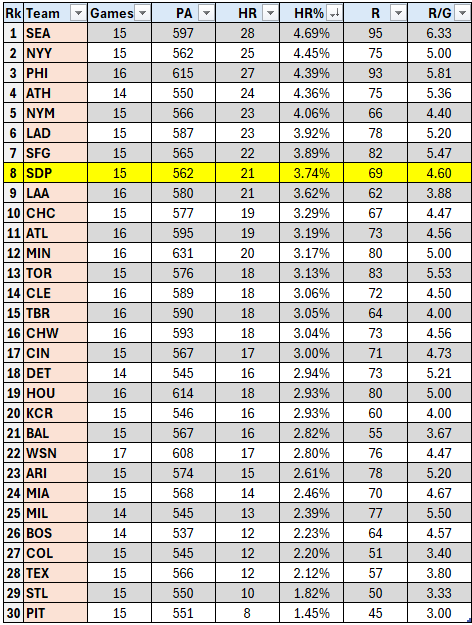

The Padres have quietly slipped into the top 10 in home run rate in September.

But there’s another, more familiar, statistic the Padres continue to lead the league in for September:

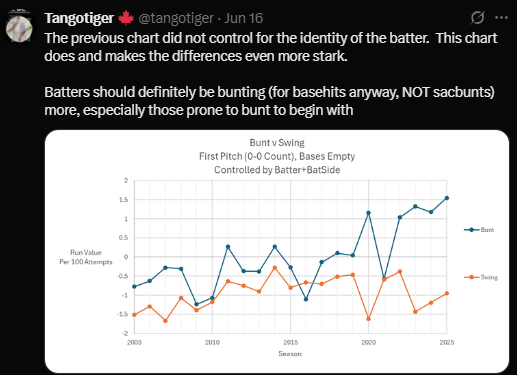

Bunts and Home Runs are downstream of swing decisions, the decision to pursue the former precludes the latter. This decision is one of the few things a hitter truly controls as he enters the batters box.

The current received wisdom is the decision to pursue the bunt is playing small ball, an amorphous term, but one we define as sacrificing some run-expectancy for another outcome of interest. But that isn’t always true. Bunting and swinging for home runs are complementary strategies in run-maximizing if used correctly. Two innings, against teams that couldn’t be more different, displayed how the team can use swing decisions intelligently to break games open. Against a regular season foe, or those likely to be seen in October.

Regular Season

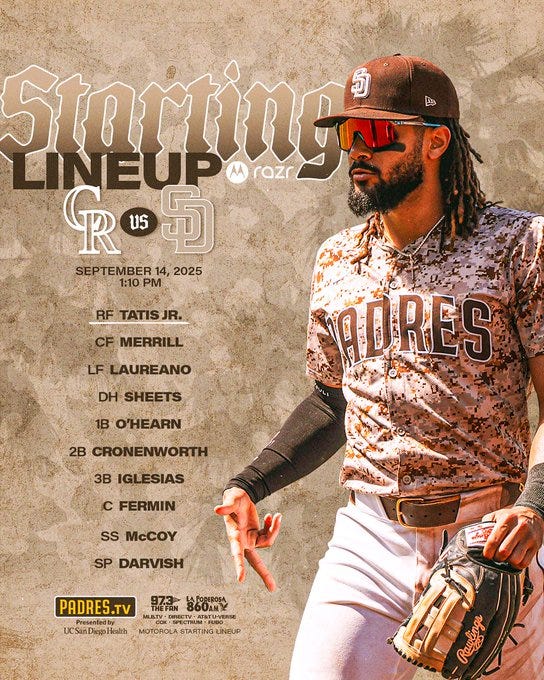

Sunday’s game against the Rockies saw a noticeably different lineup than at any point in the season:

Manny Machado and Luis Arraez got much needed days off. And the resulting lineup looked quite different. The insertion of Jackson Merrill into the second spot resembled modern lineup construction, but the defensive specialists at the bottom of the order left it looking a bit lean overall. That’s why it’s so interesting to look at how the 1st inning unfolded.

Fernando Tatis Jr.

Tatis started the game doing something he’s done at a career high rate this season: getting on base.

Though Tatis’ season hasn’t featured as much power as we’re used to, that’s begun to change recently. And it’s because of swings just like this.

Although this was a ground ball single, the swing was designed for damage:

You can see what the swing path was set up to do had the contact been a bit more flush:

Tatis, a notorious tinkerer, has changed his stance and swing shapes dramatically as the season has gone by. But his approach at the plate has been very different as well. He’s set a career high by a wide mark in walk rate, and a career low in strikeout rate. But his home run rate has suffered:

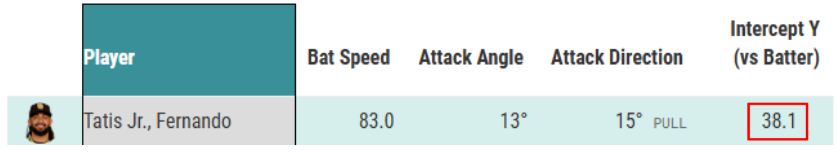

Eno Sarris distilled his thoughts on Tatis’ swing in a recent article with Dennis Lin, noting that one of the biggest differences as the season has gone on is how far Tatis is letting the ball travel (a stat captured by the Y-intercept stat on baseball savant, the distance from home plate toward the pitcher’s mound where a batter tends to make contact with the ball). As the bat travels through its path it gains bat speed, and becomes more optimized for loft, and of course the attack direction becomes more pull oriented the further out in front a hitter is. Here is the Y-intercept on the swing above:

Indeed, you can see significant changes in the Y-intercept through the season:

There are tradeoffs for trying to ambush pitches out front, primarily more whiffs/strikeouts. That is an acceptable tradeoff for more power (up to a point). But more importantly, this swing decision was so good because it came on a pitch in the strike zone with less than two strikes. Swinging and missing carries no harsher penalty than taking the pitch would. It’s impossible to strike out. A hitter gifted with power as prodigious as Tatis’ should be trying to get to pulled air power in these counts every time.

Tatis has been a different hitter in September than his rest-of-season averages, and it’s probably not a coincidence that as his approach has shifted to hitting the ball further out front his profile has started to more closely resemble his prior seasons:

He remains the team’s table setter and it’s interesting to compare how the September profile contrasts to the rest of his season:

The Padres need slugging in the playoffs, and last season Tatis was the biggest contributor to the Padres offense in October which put up the second highest home run rate in the playoffs:

It’s tantalizing to consider Tatis finding that delicate pH balance: hunting pull-side power with count leverage, and switching modes to walk/on-base machine when the count isn’t going his way. Though he only singled to lead off the game, the swing had the potential to do more, and that’s what he could control. Tatis’ at bats will be appointment television in the handful of games before October.

What happened next was an even more interesting swing decision.

Jackson Merrill

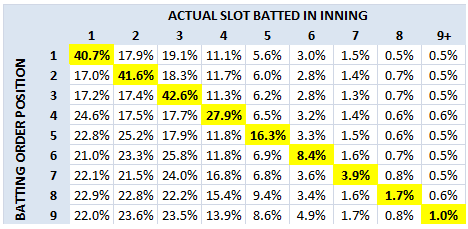

The second spot in the order has become the most important spot in the eyes of many. The second spot nets nearly as many plate appearances as the leadoff spot with a significantly higher percentage of at bats coming with runners on base:

The second spot is also the least likely spot in the order to lead off an inning:

These observations have led most teams to slot their best sluggers into the second spot in the order to take advantage of the additional base traffic and high at bat totals. The Padres had opted for a different tack all season with Luis Arraez resembling a more traditional bat-control number two hitter, and willing participant in small-ball. But with Arraez out of the lineup Sunday it was Jackson Merrill that batted second. The move made the Padres resemble most modern lineups with a power bat in each of the first six spots in the order. Which is why it was genuinely funny to see Merrill do this in his first at bat:

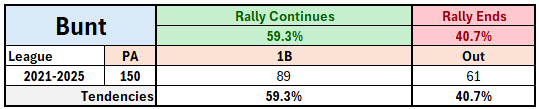

We’ve discussed the Padres’ use of small-ball, especially the use of the dreaded 1st inning sacrifice bunt to move a runner from first to second. The Padres have attempted this play 8 times in 2025, leading the league. At first this looks like a 9th attempt. But it wasn’t, not exactly. There was a key difference. Watch again how this play unfolds:

The third baseman was playing very deep, and shaded to the shortstop side:

Marquez had to scramble for the ball because of the Rockies’ defensive alignment. He knows if the ball gets past him there was no one to field it. And he couldn’t make the play.

The third baseman was beyond a crucial, measurable threshold:

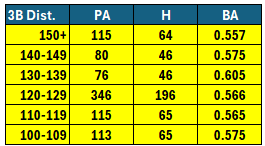

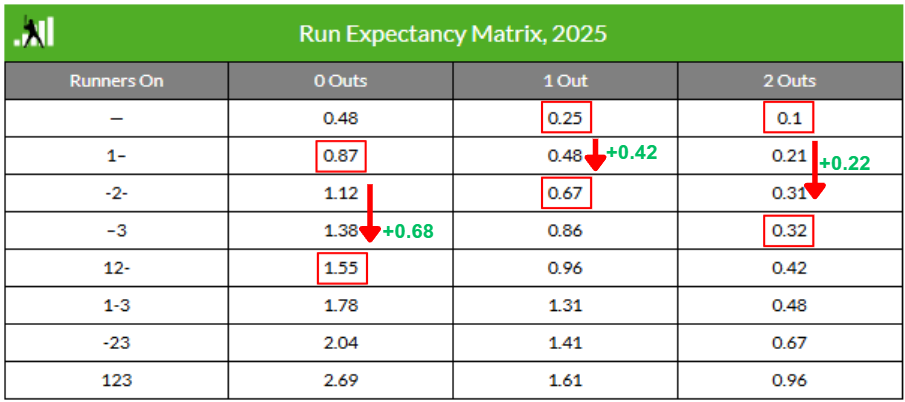

When the third baseman plays deeper than 120 feet the result of bunt attempts for base hits are staggering.

A quick explainer: One of the intractable difficulties in estimating the success rate of a bunt for a base hit is that the hitter’s intent is not in the box score. With any runners on an unsuccessful attempt will be recorded as a sacrifice bunt, and you can never know if it was just a straight sacrifice or an attempt at a hit. But there are two situations in which it is certain a hitter is bunting for a base hit rather than a sacrifice:

When the bases are empty, or

When there are two outs

Although these were not the exact base/out conditions during Merrill’s at bat, they are a useful cohort to extract the expected value of bunting for a base hit with the specific defensive alignment in front of Merrill.

When Merrill bunted, the third baseman was 121 feet from home plate. Merrill is also left handed which makes bunting into the empty space on the left side of the infield a bit easier. Here is the cumulative performance of left handed batters bunting with no runners on for the past five seasons, stratified by third baseman starting distance from home plate:

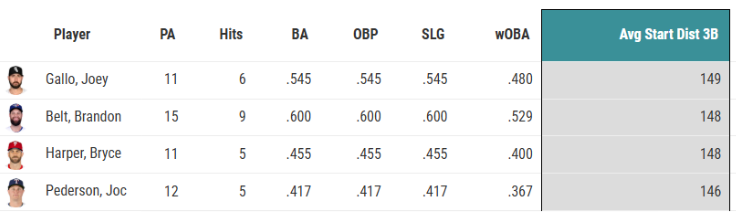

The league as a whole bats .481 on all bunt attempts with the bases empty. One might imagine these results come from speedy players skewing the results. But it isn’t just speed. There are four players in the past five years who’ve attempted double digit bunts with the bases empty, and an average third baseman starting distance more than 140 feet from home plate, they’re not exactly track stars:

Some hitters both recognize this inefficiency, and are willing to take the easy bases when the defense offers them.

And that’s one of the keys to Merrill’s bunt: the defense gave him the opening. He couldn’t control that. But once the terrain in front of him changed, there was an opportunity he could control. To take the right club out of the bag.

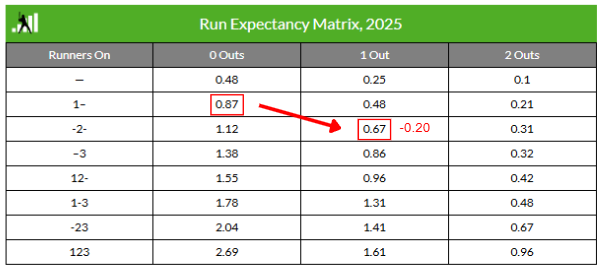

Merrill’s swing (bunt) decision was a bigger play than it seems at first, too. It provided more run expectancy than a bases empty double with one out, or a triple with two outs.

This was not small-ball. There is no tradeoff for more total runs. This is simply a run-maximizing strategy. Lumping it together with run-sacrificing small-ball strategies creates a confusing taxonomy. The dynamics of this play are the mirror image of the sacrifice bunt; the defense was the one conceding outs. In the modern game a more sensible taxonomy of swing decisions is whether the decision is run-maximizing, or run-sacrificing.

Although this was yet another instance of the Padres two hitter dropping a bunt, it was not a run-sacrificing strategy because of the opportunity the defense presented. And that probably does have something to do with putting a power bat in that spot. The same opportunity just hasn’t been there when Luis Arraez has bunted in the same 1st inning situations:

Defenses game plan very differently for Arraez. And that’s something to consider in short series when decisions made along the margins might separate evenly matched teams.

Bunting has become a rare and scorned play over the last 25 years. And with good reason, for certain bunt decisions. But bunting for base hits, especially when the defense is conceding it, has become underutilized:

There is overwhelming evidence that major league baseball has thrown the baby out with the bathwater when it comes to the use of the bunt. Banning all bunting was a strategy that could get teams ahead of the pack when the league wasn’t using information properly. But that wisdom has grown creaky over 25 years, clinging to it too steadfastly can drag a team down today. It’s time to update.

Tatis and Merrill set up a potential big inning through swing decisions that couldn’t be more different, but each was suited to the terrain the player saw before them. The next swing decision continued that trend

The Table Is Set

In the 1st inning offensive strategy should revolve around run-maximizing. Because the team does not know how many runs will be needed to win the game. Taking the easy bases defenses concede avoids outs and sets the table. But once runners are on the best way to run maximize is to hit for power.

Ramon Laureano understands this. He worked a 1-0 count and took this swing:

Laureano wasn’t able to execute. He can’t fully control that. A hitter’s execution is a factor of his underlying skill, the execution from the opposing pitcher, and the stochastic undercurrents of a game in which the very best players still fail most of the time. But he controlled what he could: a powerful swing in favorable count leverage:

Specifically a swing optimized for launch to the pull side, the best way to hit for power. It won’t work every time. But it will never work if a hitter doesn’t make the right swing decision. This wasn’t a time to bunt. The table was already set. It was time to clear it. The outcome wasn’t good, but the underlying process was:

The next swing decision was perhaps the most interesting of the day.

Ball Fore

Gavin Sheets was next up, batting cleanup. He faced the same situation as Laureano: runners already on base adding scoring leverage to extra-base hits. Sheets worked the count to 3-0. And here Sheets made the only swing decision that might be more controversial than a bunt:

The automatic take on 3-0 is one of the most deeply ingrained parts of the baseball orthodoxy across all levels of play. And it might be the strategically correct decision in little league because kids are just not very good hitters. But as you escalate up the ranks of organized baseball it becomes more important to factor in the quality of the hitter when making swing/take decisions. Major League hitters are capable of hitting home runs. Here are the league wide results of swings on 3-0 counts since 2021:

75 home runs in 606 plate appearances is a 12.3% home run rate. For reference in 2001 Barry Bonds hit 73 home runs in 664 plate appearances, a 10.99% home run rate.

This is avant-garde in the baseball orthodoxy. But it shouldn’t be, for the right hitters, when the situation calls for it.

Both Sheets and Laureano understood the assignment. They are capable of hitting for power, and there were runners on. They both took very competitive swings oriented for pulled air power:

They didn’t execute. But that’s something they can only influence, not fully control. They controlled what they could. They reached for the driver.

Ryan O’Hearn

With two outs and a runner in scoring position the Rockies didn’t give O’Hearn much to hit:

O’Hearn saw one strike on the outer half of the plate, and didn’t expand the zone, choosing to take three pitches in the shadow zone. Sometimes the best swing decision is the one you didn’t make. He drew the walk to load the bases.

Jake Cronenworth

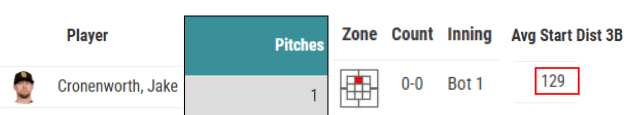

With two outs and the bases loaded in a tied game in the 1st inning this is the defensive alignment Cronenworth saw:

You can see him survey the left side of the field for a moment before locking in to the pitcher:

If you’ve read this far you can probably guess what he saw.

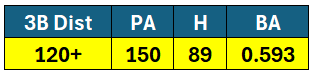

The third baseman is 129 feet from home plate and shaded to the shortstop. This is also one of the two situations we mentioned above where a sacrifice bunt is not possible, because there are two outs. Every bunt with two outs is for a base hit1. Since 2021, left handed batters who bunted with two outs in an inning hit safely in 187 of 360 attempts (.519 BA). Here’s how they did when the third baseman was more than 120 feet from home plate:

Although there were still runners on base putting leverage on extra-base hits, there were now two outs. And Cronenworth, though a capable hitter, has a far lower extra-base hit rate (6.5%) than Sheets (9.5%) or Laureano (10.9%). You can use Cronenworth’s season statistics to project the likelihood of the different possible outcomes of swinging away, and the historical outcomes of trying to bunt for a base hit with the third baseman so far back to project how the at bat might unfold depending on Cronenworth’s swing decision:

The defensive alignment gave Cronenworth the opportunity to tilt the odds of a successful at bat with a decision he controlled. And this time he executed perfectly:

The updated 2025 run-expectancy for a team with the bases loaded and two outs is 0.96 runs:

This is overwhelmingly populated by at bats in which the hitter swung away (bunts comprise 9 of the 9708 plate appearances with bases loaded and two outs since 2021 league wide). This is the expected value of a swing.

Calculating the expected value of a Cronenworth bunt is simple. There is a 59.3% chance of successfully plating a run and keeping the base/out state the same (meaning an intact 0.96 run-expectancy for the ongoing rally after the successful bunt already scored a run). There is a 40.7% chance of an unsuccessful bunt leading to 0 runs.

0.593 * (1 + 0.96) + (0.407 * 0) = 1.16

The run expectancy for a bunt is 0.20 runs higher2 than for swinging away. This is the exact decrease in run expectancy a team incurs with the dreaded sacrifice bunt of a runner first to second:

This is not small ball. This is playing for the big inning.

This was as unorthodox an inning of baseball as you will see. This is what maximizing expected value using game context looks like. It’s different for every hitter based on what they can do well. You don’t necessarily want Gavin Sheets trying to bunt even when presented with the same opportunity Cronenworth saw, both because he is a much better power hitter, and because…

This is how a team can maximize its chances to win. Not by being married to any specific ideology, playing only small-ball or only for the long ball. Playing smart is something a player directly controls, if he has a team culture that permits self-directed situational decision making.

That culture can cut both ways. At times, the Padres indulging in the small-ball bunting of an extinct era has made them look like dinosaurs—too primitive to be dangerous in today’s game. But add a little modern cunning, and suddenly you’re staring at the raptors in Jurassic Park, figuring out how to turn door handles.

Degree Of Difficulty: Playoffs

It’s one thing to outwit the listless Rockies. But on Wednesday the Padres faced an extremely talented team fighting for its life.

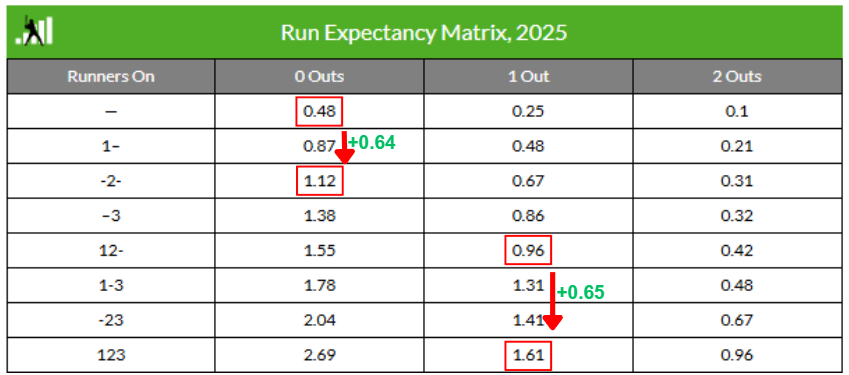

Tied 2-2 in the top of the 5th Jake Cronenworth led off with a hit-by-pitch. Elias Diaz was up next. Diaz had grounded into a double play in his last at bat. The Padres opted to have him sacrifice bunt Cronenworth to second base:

This is considered one of the least efficient plays in baseball. And it’s fair to question whether it was a good idea. But it also virtually assured that as the lineup turned over to Fernando Tatis he’d have a runner in scoring position, with a good chance he’d be pitched around to get to Luis Arraez. That’s exactly what the Mets did, showing Tatis only one off-speed pitch in the zone:

Tatis walked to put runners on first and second for Arraez, who has grounded into 11 double plays this season.

Arraez is a mercurial player. He does a lot of things most players don’t do. For better or worse, one thing he always does is survey the opposing defensive alignment before stepping to the plate:

This is what he saw:

All season when Luis Arraez has laid down bunts the third baseman has been nearly even with the bag. Wednesday he saw something different:

This wasn’t a typical Arraez sac bunt. It wasn’t a sacrifice at all. It was reading the terrain and taking the right club out of the bag.

The run-expectancy change was more than that of a leadoff double:

The run-expectancy matrix by virtue of the way it is calculated implicitly assumes a league average hitter is at the plate. But it wasn’t a league average hitter coming to the plate now with the bases loaded:

Smart, dynamic baseball plays irrespective of opponent. It works in the regular season. It works in the postseason. It can be a differentiator.

An Article Of Faith

Baseball is a probabilistic battleground where talent and decision making tilt odds, but cannot ensure victory. Certainty is outside the reach of mortal design. It rests in the hands of the baseball gods. Maximizing the expected value of a play is the most agency a player, or team, can hope to exercise. Seizing the opportunities that present themselves. Getting the decisions on the margins right. All but one team will fail. Belief that your team will be the sole survivor is always irrational. Always an article of faith.

Keep the faith.

The break-even success rate where bunting = swinging is 48.98%, so even if the presence of the force play on the bases decreases success rate by 10% it is still a run maximizing decision to bunt for the base hit over swinging away.

Incredible analysis. Makes the Padres look like chess players over the last couple days while much of the season they’ve looked like they’re playing checkers. Hoping Michael King can find his groove! Great to see Merrill heating up at the right time.

Excellent work, as usual. I greatly appreciate your efforts.