You know your team is struggling in the clutch when their bedraggled social media account starts tweeting ‘highlights’ of Manny Machado grounding into a fielder’s choice:

From: @Padres

The downfall of the 2023 Padres has been clutch performance. To many people, “poor clutch performance” means “bad luck”, because the received wisdom around clutch performance is that it’s simply luck, and nothing more.

It’s true that baseball involves more luck than most sports. And it seems inevitable that the Padres front office will shroud themselves in “bad luck” narratives, which place the blame for this dour season on some ephemeral, uncontrollable hand of fate…and away from themselves. Which strengthens their argument that they should continue to get paid to run a baseball team.

As we’ve said, it would actually be very good if everything that’s gone wrong this season was just bad luck. That would mean that the Padres could change nothing and expect the team to perform better. But is the Padres’ performance just bad luck, or is something else in the mix?

Before we answer that question, let’s review a few important points on the concept of clutch performance:

First, clutch performance does not determine how good a team is. Clutch compares the performance of a team (or player) in high leverage situations to their normal performance. This is why the 2018 Dodgers can be one of the worst clutch performing teams in history and still make the World Series: They were a really good team, so even if they underperformed in clutch situations compared to their normal selves, they were still better than most teams.

Second, ”Clutch performance” is measured through several statistics, one of which is actually called ”Clutch”. That stat weighs win probability added against the leverage of the situations in which the player/team performed. But there are many statistics that can describe different aspects of clutch performance (e.g. BA w/ RISP and two outs). But the good and the bad (actually terrible) news is that no matter which stat you prefer, the 2023 Padres are remarkably bad in the clutch.

Third, there is a difference between describing clutch performance in terms of outcomes, and describing clutch performance as a specific skill. To say “the ’23 Padres’ aren’t clutch” isn’t necessarily a comment on their skill; it’s an objective statement about their outcomes. And it’s why we say that, through 131 games, the Padres were the worst clutch performing team in the history of baseball by several measures.

The Padres are currently putting up the sixth-worst season in baseball history according to Fangraphs ‘Clutch’ statistic, and bear in mind: This is a counting statistic, and about 20 percent of the season is still to be played.

That the ’23 Padres have been terrible in the clutch is not really debatable. What is debatable is how much of their failure is attributable to luck. And the received wisdom is ‘all of it’.

In medicine, there’s a concept called a ‘diagnosis of exclusion’. In this situation, no test confirms that a condition is present; the diagnosis is made by excluding competing diagnoses. The diagnosis that clutch is just luck is a diagnosis of exclusion. People who believed that some players just were clutch – that old “he’s got ice-water in his veins” logic – were never able to summon convincing statistics showing that declaring a guy to be “clutch” had any predictive value. In the absence of any positive proof for a competing explanation, “clutch is just luck” became the conventional wisdom.

But because “clutch is just luck” is mostly a statement about the absence of proof to the contrary, it should wither when evidence of an alternate explanation emerges. And there might be an alternate explanation for poor clutch performance: It seems to be partially related to approach.

As we’ve noted before, the Padres’ woes in the clutch seems to be partially related to their adherence to the “three true outcomes” (TTO) approach. Here’s a reminder about what the TTO approach is:

The three true outcomes are strikeouts, walks, and home runs. They’re called the “three true outcomes” because they don’t involve any luck around what happens when a ball is put in play, because none of these results in a ball in play.

The TTO approach to hitting was first articulated by Ted Williams in his book “The Science of Hitting”. It has been widely accepted as a run maximizing strategy over the course of a season.

Mario DeGenz described the approach well: “TTO-heavy hitters generally tend to follow one basic plan of attack at the plate: wait for a specific pitch you think you can hit 450 feet, take the pitches you can’t put a good swing on, and whenever you do get a pitch you can handle, swing hard.”

The logic is that a walk is nearly as good as a hit. A home run is much better than a single. And strikeouts are an acceptable tradeoff for more total runs scored.

TTO teams are willing to accept the tradeoffs implicit in the approach. That is, they’re willing to sacrifice contact, and accept strikeouts for more total runs scored over the course of the season.

The final point is the most important for understanding why the TTO approach will underperform in the clutch. It is the tradeoffs (more strikeouts, fewer hits overall) that are implicit to the approach that cause it to underperform in terms of win percentage added in the highest leverage moments of the game. The most important thing isn’t that walks are worse than hits, or that strikeouts are worse than both: It’s that the tradeoff inherent in the approach affects certain game situations that have a major impact on winning or losing.

When we’ve written about this before, we’ve done so without getting too deep into the numbers. So, this time, let’s dig into the numbers, and hopefully get a bit closer to determining if a portion of clutch performance is not attributable to luck.

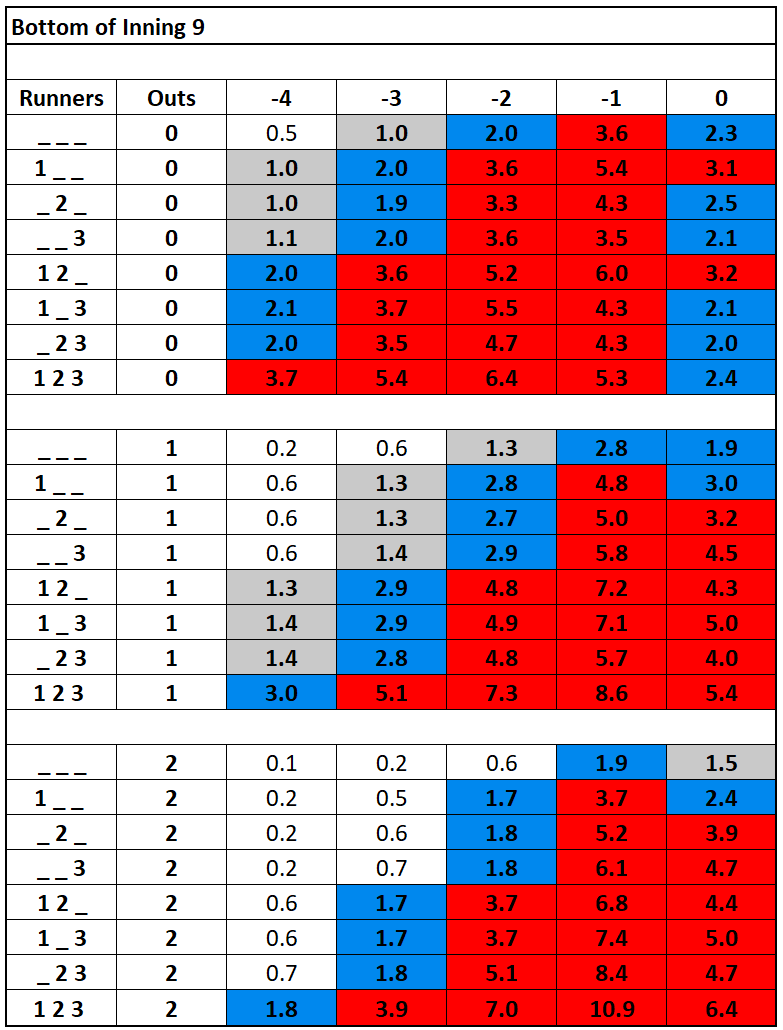

The best place to start is the leverage tables that define clutch situations. These tables include a description of every possible game context, and a leverage index that describes how much an at-bat can change the win expectancy in that game relative to average. These tables are broken down into half-inning summaries; the summary for the bottom of the ninth inning looks like this:

The left most column -- ”Runners” -- describes the base running situation when a hitter is up to bat. The next column – “outs” – shows how many outs there are. The top row of the remaining columns – “-4, -3, -2, -1, 0” -- shows by how many runs a team is trailing (for any other half inning, it would also show the situation if the team is ahead, but this is the bottom of the ninth, so it only shows trailing). White cells show low-leverage situations, gray cells are medium leverage, blue cells are high leverage, and red cells are very high leverage. The red and blue cells are the most important at-bats in the game.

Baseball has seen many thoughtful study designs looking for evidence of clutch performance. But those studies always compared a hitter’s performance in clutch situations to their performance in other situations. That is: They’re trying to answer the question “Is Player X clutch.” We’re interested in a different question, namely: “Is a player with Hitting Style X more valuable in the clutch than a player with Hitting Style Y assuming that they both perform at their normal levels?”

We don’t need enormous amounts of data to analyze this question. We just need to look at the tradeoffs that come with the TTO approach. Consider a simple example: a tied game in the bottom of the ninth and a runner on third. Any hit wins the game. Those situations are represented here in green:

In these situations, approach obviously matters. Since any hit wins the game, the best player to have up is a player who excels at getting any hit – that is, a guy who hits for average. So, coming through in critical situations – i.e. being “clutch” – isn’t only luck. It also has to do with a player’s approach.

In the tie-game-runner-on-third bottom of the ninth situation, the more-homers-but-more-strikeouts tradeoff that’s part of the TTO approach is no longer a good trade. With two outs, a strikeout carries a 100% probability of ending the inning. The math is pretty simple: In that context, every extra strikeout cancels out a home run. In fact, in that situation, trading any decrease in batting average for an increase in home runs is a bad strategy. The same lessons can apply to other high-leverage situations: Trade-offs that make sense in other game situations cease to make sense.

To wit: in most very high leverage situations in the bottom of the ninth a single could either tie (yellow) or win the game (green):

In every very high leverage situation above, a single is massively more valuable than it normally is. It remains true that the TTO approach increases overall run probability. But it appears to decrease win probability in certain high-leverage situations because of the tradeoffs it entails.

This is relevant to the TTO-heavy Padres. What we can say is that it would probably be good if their players could switch strategies in late game situations (specifically: Stop swinging for the fences and hit for more average). Of course, it’s easy to type “just become Tony Gwynn in the later innings”, and much harder to actually do it. We’re in the realm of the theoretical here; putting the theory into practice might not be possible. But it seems clear that the best type of ballplayer is probably one who is TTO most of the time but becomes a contact hitter late in games when the situation calls for it.

We can probably reject the “just” in the sentence “clutch is just luck”. We can reject the diagnosis of exclusion. There is definitely luck involved: Only about 15 percent of a team’s at-bats come in high-leverage situations, and that small sample size means that a team can perform better or worse than expected based on luck. But even accepting the ubiquitous role of luck in all things, it also seems clear that approach to clutch hitting situations matters. And the Padres’ devotion to the TTO approach probably explains some of their struggles in the clutch. Not all. Some. Can they learn to hit differently based on the moment? Only the Padres know that. All we know is that if they can’t, it will not be totally surprising if they continue to struggle when the game is on the line.

Luck Or Process?

There’s a strange irony in the idea that the Three True Outcomes approach, so named because the outcomes do not involve luck, could contribute to failure in the clutch, an outcome that has been exclusively attributed to luck. At least until now.

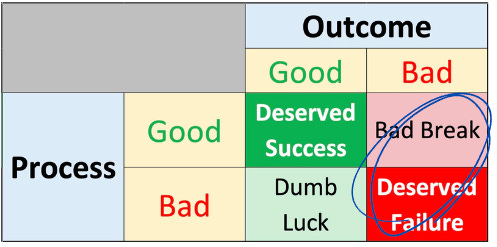

The point of this article is not to explain all of the Padres woes this season, some of which is indeed bad luck. It’s to point out that they show fealty to an approach to hitting that is reliably, demonstrably, expected to underperform in certain game situations. That is, while they’ve undoubtedly had some bad luck, parts of their process are also not well suited to every situation. When you look under the hood, past the shiny run differential, the 2023 season at least has a bit of this flavor:

If you understand what we’ve discussed above, you’ll understand why none of this is going to show up in a study of the raw corpus of available statistics. To determine if a player has the ability to switch to a contact approach, sacrificing overall power for fewer strikeouts and more total hits, you’d need to know when a player was switching modes. Only the teams and players know that for sure. But that’s not to say there wouldn’t be any evidence. If a player was switching modes to a contact oriented approach there would be visual clues. The swing would be shorter, the player’s head would be down through the point of contact, an opposite field approach. It might look something like this:

If the most notorious free swinger on the team has the ability to shorten up when the moment calls for it, would it be unreasonable to think that others might be able to do the same? Was that evidence of a deployable skill? Or just a lucky swing?

Have you seen any data on how well the tto approach does at petco park overall? Its common knowledge that the ball doesnt travel as well at petco bc its closer to the ocean, I am thinking the padres could be doubly penalized in the TTO approach because of this

Really interesting read! My only thought against it would be we don’t really seem to ever strikeout a lot, regardless of situation, in terms of K% - 9th best overall, 10th best with RISP, 13th best 7th inning or later. Maybe this is what you mean, but I wonder if the over commitment is just needing a hitter or two whose best skill is still is their ability to make contact?

I also wonder if you have any thoughts about our struggles with velocity. 47% of pitches League wide are classified as a fastball or sinker by statcast. They have easily the highest average velo’s at 94 and 93.3 and we rank 18th and 17th in terms of run value/100 against those pitches. We’re also one of the very worst against cutters which are the next hardest at 89 mph but only thrown 7% of the time. We usually seem to handle sliders, curves and change ups.

We’re inconsistent against starters, but wondering if the late inning struggles are cause we’re facing a bunch of dudes who just throw hard (and typically with good movement)?