We should have still been watching Padres baseball when the playoffs started Tuesday. In the end two wins separated the Padres from the postseason. Two games across a 162 game season is 1.2%. That’s the extra win percentage that was needed to survive this most ill-fated of seasons. That’s why it’s worth noting when a team consciously leaves marginal win probability on the table. And why it’s worth giving it a name: Padresing: capitulating to the whims of fortune, refusing to exercise remaining agency when bad luck strikes. The term should enter the Padres grimoire, invoked when future decision makers are tempted to place some other priority above winning. Marginal strategies matter. So does culture. And the two are intertwined.

The Padres failures in clutch hitting were historic; by several measures, they were among the worst – perhaps the worst – clutch-hitting team in MLB history. Luck was definitely part of this. It wasn’t all of it, though; their tendency to swing for the fences even when a single (or productive out!) might suffice partially explains their struggles in the clutch. And yes, ‘partially’ is carrying a lot of weight there, but that’s what marginal win probability left on the table looks like. And it adds up.

As the season wore on, clues emerged as to why clutch hitting was such a struggle for the Padres. This excerpt from Dennis Lin’s recent article bears repeating:

Situational baseball is not their strength.

“That’s what (good offense) is — go up there and try to put the ball in play, try to bring that guy in instead of hit 500-foot homers,” Soto said. “That’s what’s been lacking a little bit, just knowing the moment and the situation.”

“We’ve talked about it, addressed it. Everyone’s aware of it. We’re trying,” another player said. “For me it’s almost like, these guys don’t really know how to do it.”

The players understood there was a problem, and yet there was resistance to change. This is what a culture problem looks like. Asking hitters to take a contact-oriented approach is absolutely asking them to make a personal sacrifice. Players are evaluated on their corpus of work across a season, with almost no attention paid to whether the player was a good situational hitter across the season (in part because the conventional wisdom remains that clutch hitting is pure luck). Asking a player to forgo the possibility of a deep home run every time a single would suffice might help the team win slightly more often, but it could also reduce the player’s long-term value. Therein lies the tension. The players surely understand this. Nonetheless, the organization kept its head in the sand about the problem; precious roster spots that might have been given to a contact hitter were instead given to players the team felt it owed. Now that players have gone on the record with Dennis Lin, the team’s most prominent beat writer, acknowledging the problem existed, perhaps it will be addressed going forward.

The above described culture was insidious, not being acknowledged until the season was nearly over. But what loomed large all season and undoubtedly shaped the team culture was the special treatment given to a particular player. By now, everyone knows the Hader House Rules:

Never pitch more than three outs

Only pitch in the ninth inning or later

Never pitch more than two games in a row1

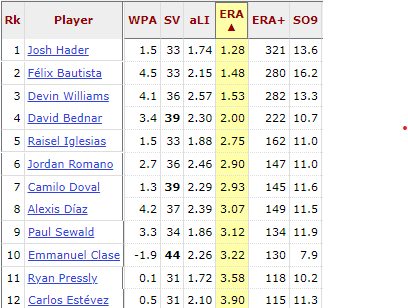

Josh Hader is a very good pitcher. And by traditional measures, he had a stellar season. Of the twelve pitchers this season that amassed 30 saves, Hader had the best ERA and best ERA+ -- a staggering 321 – and also had the second-highest strikeouts per 9 innings. That is dominance of the traditionally important closer statistics:

But the most remarkable part of that chart is probably the first column: For all Hader’s excellence, he only compiled a Win Probability Added (WPA) of 1.5. That’s one of the lower marks on the list:

Josh Hader gave the Padres the same win probability added as several less-talented pitchers, about 1.5 wins across the season. And perhaps more telling is that on this list of prolific closers, Hader, playing on a team that notoriously struggled in close games (9-23 in one run games, 2-12 in extra innings) where high leverage moments abound, faced the second-lowest average leverage index in the situations in which he was deployed:

This is because of the Hader House Rules. The Padres were unable to get maximum value out of their closer because the rules hamstrung them. Inferior relief options were forced to field high leverage moments that should have gone to the closer. That’s what leaving marginal win probability on the table looks like.

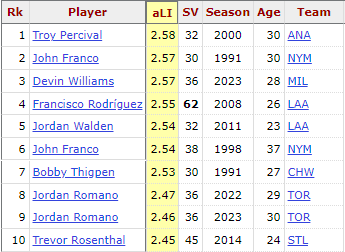

It was always a little mysterious why the Brewers gave up Hader for so little. Sure, they had Devin Williams who is an excellent reliever. But the real clue might be in the chart above. The Brewers deployed Devin Williams when, and how they needed him, including a five out save in May. The average leverage index (aLI) Williams saw this season was an astounding 2.57. Among closers that reached at least 30 saves, Williams aLI in 2023 is tied for second highest in baseball history2:

Deploying Devin Williams this way allowed him to amass an excellent WPA of 4.1, roughly four wins added across the season. And this approach is incompatible with the Hader House Rules. It would be virtually impossible for Hader to touch that number using the Padres’ current approach.

Hader’s rules seem to be designed to optimize his value as a prospective free agent. We actually don’t begrudge Hader for crafting these rules; people tend to optimize for what’s measured. It’s in his self-interest to seek whatever statistics make him a more valuable free agent. Perhaps the lesson to take away from Hader’s ’23 season is that the traditional methods for evaluating the value a closer brings to his team need to be updated. Dominance in lower leverage accrues nice looking traditional statistics, but a team may be better off with a less dominant pitcher who can be deployed to maximize win probability. We’re also cutting Hader some slack here because the ultimate responsibility is with the organization; they’re the ones who allowed special rules for one player. Did elevating the interest of an individual over the team’s interest create a culture where players learned to shun sacrifice? Maybe, we don’t know. But it’s easy to imagine that situation being true.

2023 laid bare that the goals of an organization do not always align perfectly with the self-interest of the individuals within the organization. Where the organizational goals and individual self-interests do not perfectly align, it is the culture of the organization that keeps members pulling together towards shared goals, even when that may call for some sacrifice. And it’s a cultural failure when the members aren’t pulling together towards that shared goal. Fans of baseball often wonder how culture could possibly have a meaningful effect on the outcomes of a largely individual sport since the players are incentivized to play their best at all times. We hope the above illustrates that there are specific scenarios in which what is best for the team is not necessarily what’s best for the pure self-interest of the player, and why culture can materially affect the outcome of such an individualistic game.

One way to look at this season is that if the team had good or even average luck, the Padres would have made the playoffs. That’s true. But when bad luck strikes is precisely when marginal decision making starts to matter. You can’t control luck. You can only control what you do; you can maximize your chances of winning regardless of luck. The Padres failed to maximize those chances by giving at-bats to underperforming players, failing to hit situationally in high-leverage settings, and elevating special rules above a focus on winning. Those choices mattered. Of course, they weren’t supposed to matter. The team was supposed to be so good that marginal decisions wouldn’t matter. But then luck reared its ugly head: terrible slumps, badly timed injuries/illnesses, BABIP woes (including some mysterious ‘deadball’ outcomes that still defy explanation), inexplicable errors, and a few ridiculously bad calls. All that bad luck put the Padres on the margin, and the team’s marginal decisions led to missing the playoffs by two games. 2023 was the apotheosis of Padresing.

The 2023 season was disappointing, but also fascinating. It is truly remarkable to be mediocre in the specific way the Padres were. In a way, that’s something to be grateful for. The team didn’t reach the lofty heights we thought it would, we weren’t treated to an exciting playoff run, but we learned. We learned about baseball, and baseball always seems to teach us about being human. So…thank you for that, 2023 Padres. We’ll miss you in a way that we didn’t quite expect. Until next season: So long, and thanks for all the RISP.

Hader made an exception to this rule twice across the 162 game season. Huzzaaah!

Jordan Romano’s 2023 season also made the top 10. We noted before that teams may be better off deploying their ‘closer’ when the leverage of the moment calls for it rather than sticking to the conventional ninth-inning only role. It looks like two playoff teams this year may be ahead of the curve.

Of all the controllable factors, the Hader House rules are the most egregious example of “Padresing.” And the most infuriating. There are at least 5 games I can think of that would have likely turned out differently if he had been used as “the highest leverage pitcher.” If Mookie Betts, Freddie Freeman, Will Smith and Max Muncy are the next four batters in the 8th inning of a 1 run game, you pitch your best reliever. Let your second best go against the rest of the lineup flotsam.